I threw Catholics under the bus at a book reading.

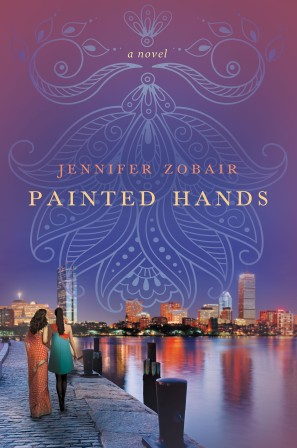

I didn’t mean to and, as a former Catholic, I felt awful about it. I was promoting my novel, Painted Hands, about dynamic, successful Muslim women in Boston. During the Q&A, someone asked why I’d converted to Islam. Pressed for time, I explained that I’d tried hard to be a Catholic feminist, referenced the fact that there was no Original Sin imputed to Eve in Islam, and admitted I’d struggled with the Trinity and welcomed a religion where Jesus was revered but not divine.

Afterwards, I fretted about the comparisons. “That was bad, wasn’t it?” I asked my husband. “Maybe,” he said gently, “stop at the fact that there are feminist interpretations of Islam. Maybe don’t say anything about other religions.”

When you’ve left one religion for another, the implication is that you did find something better. But my rushed, blithe response glossed over the very real struggles I’ve had as a woman in Islam. I’d tried hard to be a Catholic feminist, I told that crowd, but what I didn’t say was this: I have also worked hard to be a Muslim feminist.

Those efforts began as soon as I decided to marry a Muslim man and convert. When my engagement gifts included books on Islamic morals and manners glorifying traditional gender roles, it was easy for me to dismiss them as cultural or antiquated. It was not so easy to dismiss interpretations of Surah 4:34 of the Qur’an.

This verse is commonly, and recklessly, known as the “beating verse.” To deal with serious martial disorder, this verse advises a husband to admonish his wife, then to refuse to share her bed, and finally to “daraba” her. Though daraba has dozens of meanings in Arabic, it is often translated in this context as “to beat.”

Troubled, I consulted a respected imam. He justified this translation by saying that “in some parts of the world, women are like children.” I was horrified. Where in the world are women like children? Who thinks children should be beaten? And what kind of religious leader traffics in such beliefs?

To be a woman in Islam, I soon discovered, was another exercise in separating the words of men from the nature of the Divine.

It took some effort to reconcile Surah 4:34. A well-meaning woman at a halaqa explained that the hitting should be a light tap. I nodded but was far from reassured. I looked to Muslim feminist scholars and discovered that daraba could mean to “condemn” or “set an example.” I found Laleh Bakhtiar’s version of the Qur’an in which she translates daraba as “to go away from.” While my spirit soared, the (male) head of a Muslim organization said that we will not suffer such “pro-woman” interpretations.

Watch us.

I’ve had other struggles with Islam, including gender separating, which is meant to control sexual attraction outside of marriage, but which often ensures that mosques are male spaces and religious decision-makers are men.

Though the Qur’an is silent on the matter, most scholars insist that women cannot lead men in prayer. Even when a woman is fully covered, scholars argue, men cannot control themselves when a woman bends during prayer. Never mind that when a woman bends, the men should be bending, too, and therefore looking at the floor.

If you’re the kind of man who cannot help but stare at a woman’s backside when you’re praying, it is not her problem. It is your problem, and, I might suggest, a pretty big one.

This restriction on female religious leadership, predicated on the idea that even a covered woman is sexually corrupting, prevents egalitarian and pro-woman readings of the Qur’an from being preached in mosques with sufficient frequency. It ignores that women are scholars, that they might have something to say, especially about Qur’anic versus that affect them. It over-sexualizes men and desexualizes women by insisting that women can think pure thoughts while praying behind men, but that men cannot manage the reverse. Finally, it’s infantilizing, resulting in grown women praying behind boys who have barely reached puberty, even though the Qur’an states that the one who should lead the prayer is the one with the most knowledge.

Muslim feminists are tackling these issues head on. Just like I devoured books by Catholic feminists like Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza in college, I find comfort in the work of Muslim feminists like Fatima Mernissi, Leila Ahmed, Amina Wadud, and Asma Barlas. I’m encouraged by women-led Muslim prayers and the movement toward inclusive prayer spaces. But they are not without controversy, as I illustrate in Painted Hands. There is still work to do, for Muslim feminists in general and this Muslim feminist in particular.

Muslim feminists are tackling these issues head on. Just like I devoured books by Catholic feminists like Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza in college, I find comfort in the work of Muslim feminists like Fatima Mernissi, Leila Ahmed, Amina Wadud, and Asma Barlas. I’m encouraged by women-led Muslim prayers and the movement toward inclusive prayer spaces. But they are not without controversy, as I illustrate in Painted Hands. There is still work to do, for Muslim feminists in general and this Muslim feminist in particular.

In Love, InshAllah: The Secret Love Lives of Muslim Women, Patricia M.G. Dunn writes about how her Muslim-born husband can take things for granted, and how she, as a convert, has to struggle for everything she believes. I wrap myself in that observation and let myself off the hook. When you are raised in a particular faith, it’s not threatening to question it. But when you’ve converted, radical questioning is often perceived as subversive, both by those who didn’t trust your conversion in the first place, and by you, because you know deep down that if you left one faith, you can leave another.

This is both unsettling and empowering—to realize you are constantly choosing your faith. And maybe it’s not so seditious after all. Maybe faith should be active instead of passive— a grand and ongoing decision where we grapple with the parts that make us uncomfortable, bringing our best, most purposeful selves to the process.

What I should have said at my book reading is that I worked hard to be a Catholic feminist, and I’ve worked hard to be a Muslim one as well. And there is sacred meaning in both.

Jennifer Zobair grew up in Iowa and graduated from Smith College and Georgetown Law School. She has practiced corporate and immigration law and, as a convert to Islam, has been a strong advocate for Muslim women’s rights. She is the author of the debut novel, Painted Hands, about young, professional Muslim women in Boston. Her essays have been published in The Rumpus and The Huffington Post. Jennifer lives with her husband and three children outside of Boston. For more information, please visit www.jenniferzobair.com.

Jennifer,

I very much enjoyed this. Thanks for sharing. A question: How much did you know about Islam and women and feminism is Islam before you converted? You acknowledged some reasons at your reading, but the post reads as if marriage was your motivation for converting, not the religion itself.

LikeLike

Thank you, Mariam.

My conversion did come pursuant to my marriage, and because my husband and I agreed that we did not want to raise children in two different faiths, we knew one of us would convert if we got married. Because of my issues with the Trinity, it was much easier for me to accept the basic tenets of Islam–I had a dear friend in college who was a Muslim so I was already familiar with the vast similarities to Christianity–than for him to do so with Christianity. I had a working knowledge of things like the fact that the Qur’an addresses Muslim men and women directly, that women were given property/inheritance rights that even western legal systems denied women into the 1900s, and, as I said, that there was no Original sin imputed to Eve. I did not, as I discuss, have a satisfactory answer to things like Surah 4:34, or women leading prayer, but I was used to grappling with such things as a Catholic feminist, so that wasn’t a reason for me not to convert. I expected it to be a journey, and of course it has been.

Thank you for reading and for this question.

All my best,

Jennifer

LikeLike

Good luck with your choices.

LikeLike

Thank you, Barbara. I think it’s more purposeful than luck, but I’ll take the good wishes!

LikeLike

“Maybe faith should be active instead of passive — a grand and ongoing decision where we grapple with the parts that make us uncomfortable, bringing our best, most purposeful selves to the process.” Thanks for this magnetic and challenging insight, Jennifer, truly profoundly empowering, spiritually and creatively.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Sarah. I appreciate your comment so much!

LikeLike

As someone who has converted from one religion to another (I was raised Catholic, but chose Tibetan Buddhism), I struggle with the desire to protelytize and convert others. These are definitely not the ideals promoted in Buddhism, but may be vestiges of Catholicism, some deep insecurity that needs others to believe as I do, or the zealousness of the convert. Do you find yourself struggling in the same way? Do you find yourself wanting others to honor, respect, and even convert to what you have found to be truth? Do you think that this desire to convert may be the reason why your protagonist is a Muslim woman?

LikeLike

Hi Karen. Great questions! I actually feel almost no desire to convert others. I didn’t as a Catholic and I don’t now, maybe because I’ve been subject to so many efforts to convert me–either back to Christianity or to a more conservative interpretation of Islam. I do hope people respect my choices even if they don’t agree, absolutely, and I try to respect others’ choices as well.

The protagonists in my novel are Muslim because I am Muslim, and because I feel like there is this one very narrow image of Muslim women in this country. In the 16 years since I converted I have met such a diversity of Muslim women. I think the book is meant more to allow people who might not know any Muslims personally to get a glimpse of what some of our lives are like–which are very much like other women’s lives! I’m certainly not depicting all Muslim women’s experiences, even with the cast of characters in the book. I hope it’s an entertaining story, and I hope it creates discussion and, ideally, greater understanding, but no, conversion was not on my mind in writing it.

LikeLike

Hi jeniffer am abraham.I have went through all ur phost; but what I will like to say was “why don’t u went through the Qur’an again”Am sure if u did so u will find a verse there DAT will explains u about d other one.

LikeLike

This is such an excellent post. I love your closing: “What I should have said at my book reading is that I worked hard to be a Catholic feminist, and I’ve worked hard to be a Muslim one as well. And there is sacred meaning in both.” This can be applied and expanded to different “isms” and identities that people struggle with and I see it in my own studies.

Glad to have this post on this blog and a scholar like you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much, John! I just looked at your bio and am really interested in your work. Looking forward to checking out your blog.

LikeLike

Thanks Jennifer! If you’d like to chat more, jerickson85@gmail.com

LikeLike

Great, John. I will be in touch. Thank you!

LikeLike

Jennifer —

I loved this post. And like John and Sarah above, I really loved the ending (“Maybe faith should be active instead of passive— a grand and ongoing decision where we grapple with the parts that make us uncomfortable, bringing our best, most purposeful selves to the process. What I should have said at my book reading is that I worked hard to be a Catholic feminist, and I’ve worked hard to be a Muslim one as well. And there is sacred meaning in both.”) These sentiments — active feminist searching within our faith traditions and active tolerance as sacred acts — are the reason I read FAR. Thank you for underscoring our purpose here.

LikeLike

Nancy, I love how you put that–active feminist searching and active tolerance as sacred acts. Such beautiful sentiments and ones I would love to spread far and wide.

LikeLike

This made me think about how men/women make value judgments—-

We judge something as good/bad because of how we experience it. for example when we look at the statement—“in some parts of the world, women are like children.” we may judge this as bad—yet— If women were asked to expound on the topic of immaturity of men, they may discourse for hours on how juvenile their men are……..Women experience men from their perspective and men experience women from their perspective.

We can put value judgement on these human experiences while at the same time understanding that there are necessarily many perspectives because there are many experiences. That is precisely why Muslim women’s voices and perspectives MUST be heard—because without them Islam is not whole.

Moving forward for Muslim feminism, I hope it will be defined by its attitude of mutual respect—for women to hear (and not dismiss) male experiences while at the same time teaching others to hear and respect female experiences…….so that both men and women can hear (and not dismiss) other human experiences while at the same time striving for tolerance and respect.

Surah 4 verse 1

O humanity, have awe of your Guardian Lord

who created you from a single soul

Created, out of it, her mate, and from them twain

scattered (like seeds) countless men and women;-

Have awe of God, through whom you demand your mutual rights

and be heedful of the wombs

for God ever watches over you.

LikeLike

I agree that it’s important that we establish mutual respect in our religious cultures. The problem with our patriarchal cultures is that it is the masculine voice that predominates, so women’s perspectives get lost. And that’s why I’m very interested in the egalitarian societies that still exist in the world — ones where BOTH voices are heard — those that American feminists call matrifocal and European feminists call matriarchal.

LikeLike

Anon, thank you for your thoughtful commentary! I do agree that we use our experiences to make value judgments when others speak, but here I was responding to his perspective on what it means to be a child–letting him define his own terms, if you will. If he had said “women are like children,” and nothing else, then yes, my taking offense would be the result of my interpreting his statement. But he said much more–that some women are like children and therefore can be beaten. I disagree with that characterization of children–that they should be controlled through violence–and absolutely find the analogy to women offensive. I suppose that is a value judgment as well, but I hope it’s not an exclusively or even predominantly “female” one.

When women say that men are juvenile, often they are joking and even if they are not, physical harm to men does not usually flow from such statements. We cannot stop a man from thinking women are like children-in good or bad ways–but we can work to ensure that physical harm does not result.

But to your larger point, there is this beautiful quote by the great Alice Walker: “I couldn’t be a separatist, a racial one, and I can’t be a sexual separatist. It just seems to me that as long as we are both here, it’s pretty clear that the struggle is to share the planet, rather than to divide it.”

So I agree that we’ve got to listen to one another, and it has to be in a spirit of respect and equality.

Thank you for reading!

LikeLike

I simply had to respond to this comment! The person who said women were child-like or childish isn’t propagating an ‘Islamic’ view of women. It’s prevalent in the East or Asian countries (Hello Kitty?). Women of any age have to portray themselves as near juvenile to get the attention of men & consequently get the rap that ‘women are immature’.

LikeLike

I wonder: ¿How is feminist the option to reproduce the Patriarchal expectation of the “woman is the one who always must/expected to renounce and sacrifice in behalf of men/bigger goals” regarding your conversion to Islam? All the rest is rightly attached to the very well known development of Islamic Feminism. I ask this because being myself a feminist and a Muslim converted for 5 years -for the sake of Allah, since I am single- I have found many traces of Patriarchy even inside Islamic Feminism itself what make think that, despite the production of theories we are far away from really make it happens.

LikeLike

Hi Vanessa,

In my case, I don’t think it was that the woman had to renounce. I think it was two thinking people who wanted to get married, who had to figure out for whom it was an easier step. Because I had already been searching, and because I had problems with a defining tenet of Christianity, it was not a difficult transition for me. It’s a much smaller thing, of course, but I am a vegetarian and my husband was a meat-eater, and after we married he became a vegetarian because that is what I believe in for a variety of reasons, and how I wanted to raise my children. Marriage is about sacrifice, yes, and I agree with you that it should never be only expected on the part of the woman.

LikeLike

Hello,

Thank you for writing this. It gave me an insight into why some western women would convert to Islam, a question that I had never found good answers for.

I should admit that I still don’t understand it completely, though.

I understand your point that Islam is better than Catholicism dealing with some gender issues, and I agree to that. But I admit that it’s nevertheless far from perfect.

The wife-beating verse in Quran does not only give the permission to husband to discipline his wife, but also puts him in a superior position, only because men are considered to be spending from their money. There is no chance of reversing this according to Quran. There is no space for a wife to discipline her husband. The women are not the “Qawamat” upon the men; it is only the men who are “Qawamoon”.

Regardless of how gently the “beating” part is interpreted, this dynamics of dominance of male over females is preserved, and cannot be reversed or equalized.

How can one be a feminist and still believe in glorification of such traditional gender roles? This is the question that I still ask myself.

Islam might gives women the space to improve themselves in comparison to Catholicism, but it definitely doesn’t provide a space for unbounded improvement until equality.

LikeLike

Hi Saba.

I have to preface this by saying that I am not a religious scholar. I am a seeker and that is all. For me, part of dealing with this verse is understanding the time in which it was revealed–thinking about what the status of women was at that time, and how in that context this verse appears to be what was probably a radical attempt to protect women from abuse–by making men slow down and act rationally–say something, leave the bed, go away. I realize that the Qur’an is meant to be timeless, but it still did come in a specific time and address the specific social context in which people then lived. And, at that time, most men probably were financially responsible for women–and in many marriages still are–and it seems to be driving home the larger point that one should protect, not harm, someone one is financially responsible for.

As for women’s rights, divorce is permitted in Islam.If a man wants a divorce, it seems to me that he is instructed to go through these steps first, which is an attempt to work things out and change course. (A woman, by the way, does not have to “put up with” any of those steps on the husband’s part; she could seek a divorce immediately.) It also seems to me that if a woman feels her husband is causing the marital discord, she could go through these steps–she could chastise him and refuse to share a bed and walk away–or any other steps she preferred, like counseling, but she is not instructed to do so. I am a feminist, but I also recognize that domestic violence in every culture and religion affects far more women than men, and perhaps it is purposeful that a woman does not have to try at all to salvage such a marriage through these steps, which would very likely put her in danger, but may simply seek a divorce.

LikeLike

Thanks Jeniffer for writing back.

I might have been a bit unclear in my former post.

From what you just posted it is clear that both of us agree that Islam preserves gender roles that were suitable or even very progressive, for 1400 years ago, but not very much so for now.

My main question is how the feminist Muslim(ah)s or Muslim(ah) feminists deal with these contradictions (which are not limited to one or two)?

I can find in your post an “attempt” to interpret things in a more feminist way, and I think this is what most Feminist Muslim(ah)s do to deal with those contradictions: try to keep both and minimize their conflicts, by introducing feminist readings to the text (regardless of how successful it will be. With our example, your interpretation about domestic violence is very in line with feminism, except that it fails, because women are actually not granted a right to divorce, or custody of their children after it, which puts them in great pressure to stay with the abusive husband.

My point is not to defeat your argument or a feminist reading of this verse. It is just to show how these readings are usually inconsistent with Shari’ah. Hence my question: Why feminists still keep remaining Muslim while they see it is not very compatible with feminism in the long run).

This attempt of “compatiblizing ” feminism and Islam is a great thing for people who cannot give up their faith, or cannot put their feminism in priority to their faith, and give up the parts that contradicts the feminist values.

But this doesn’t apply to people who want to adapt a faith. People who are exploring a religion to decide about adopting it or not, have a chance to put their feminism in priority, and don’t adopt a religion that goes against it. So, with regard to “why some western women [with feminist viewpoints] would convert to Islam”, I actually got some insight from reading your piece, but I’m still not totally sure Why they would Not go for a Relatively Better Choice of Belief System that is less contradictory to their value system?

I honestly don’t expect you to respond to this, right after reading it. I think making a choice about adopting a belief system is very complicated and many factors are involved. Previous value systems (like feminist viewpoints) might play only one role. Other factors might be at play ( for example, I read from your comments that you and your husband were both considering converting, and then you decided, so marriage might be one?), and it might take you a while to consider all of them and see how the whole thing summed up toward Islam. And how they might be true about other converts that you might know.

But that would be great to hear back from you on this question.

LikeLike

I disagree that women do not have the right to divorce, and I think barriers to that are often imposed by the views of an imam or by school–and these rulings are of course handed down by men. And men are not, as I’m sure you know, infallible. But I don’t think that’s your point. I think you want to know why a feminist converts to Islam, and I’ve tried to explain it, in my case, as best I can. I can’t speak to anyone else’s experience. I was raised in an Abrahamic tradition. I already believed in the prophetic tradition that Islam shares. I also very much believed in the teachings of Jesus; I simply had a hard time accepting his divinity. I believe in a God who created women as equals. I struggle with patriarchal interpretations. I try to find better ones.

Another woman told me that if I just adopted the hijab, patriarchy would make sense to me and I would assume my subservient role. It seems as though you believe I cannot truly be a feminist and a Muslim. I stand in the middle of these two positions, fighting for a prophetic tradition that has had meaning for me for my entire life, unwilling to concede it to sexism, or to abandon it for something else.

Thank you for reading and for the discussion.

LikeLike

Hi Jennifer,

I converted from wahabism to a shia ismali sect and am familiar with the struggles that you faced. Yes, it starts with a man but becomes something bigger than that. We do it for ourselves in the end. To say that you or I or other women have made a decision to convert just to get married is to take away from the fact that we have raised our awareness of the faith (maybe more than those born in it) or the fact that we have made a decision to change our hereafter. Many people are dissatisifed with their birth religions but dont question out of fear of change.

My adopted community believes in esoteric meanings in the Quran and do not interperat it as the obivious. So when the scholars interperat a divine revelation into something trivial or derogatory we shrug it off.

Women in my community are not only aware, educated (99% literacy), work from home or own businesses or in offices, they are on an equal footing with the men and have the freedom to make decisions related to their personal and financial well being.

LikeLike