Sometimes we think of Greek myth as a pre-patriarchal or less patriarchal alternative to the stories of the Bible. After all, Goddesses appear in Greek myths while they are nearly absent from the Bible. Right?

Sometimes we think of Greek myth as a pre-patriarchal or less patriarchal alternative to the stories of the Bible. After all, Goddesses appear in Greek myths while they are nearly absent from the Bible. Right?

So far so good, but when we look more closely we can see that Greek myth enshrines patriarchal ideology just as surely as the Bible does. We are so dazzled by the stories told by the Greeks that we designate them “the origin” of culture. We also have been taught that Greek myths contain “eternal archetypes” of the psyche. I hope the brief “deconstruction” of the myth of Ariadne which follows will begin to “deconstruct” these views as well.

Ariadne is a pre-Greek word. The “ne” ending is not found in Greek. As the name is attributed to a princess in Greek myth, we might speculate that Ariadne could have been one of the names of the Goddess in ancient Crete. But in Greek myth Ariadne is cast in a drama in which she is a decidedly unattractive heroine.

Ariadne is a pre-Greek word. The “ne” ending is not found in Greek. As the name is attributed to a princess in Greek myth, we might speculate that Ariadne could have been one of the names of the Goddess in ancient Crete. But in Greek myth Ariadne is cast in a drama in which she is a decidedly unattractive heroine.

In the story told by the Greeks, Ariadne falls in love with Theseus, a handsome young man who was sent with 11 other Greek young people to be fed to a monster (who is half man, half bull) known as the Minotuar. The Minotuar is Ariadne’s half brother (see below). Because of her “love” for Theseus, Ariadne helps him to murder her brother. She then flees with Theseus on his boat.

However, this “love story” does not have a “happy ending” as Theseus abandons Ariadne on a nearby island–long before he arrives home in Athens. Theseus is ever after celebrated as a hero who killed a monster, while Ariadne is just another cast-off female. Whose story is this?

According the Greeks, the Minotaur demanded human sacrifice—6 boys and 6 girls sent from Athens to Crete every year. The mention of human sacrifice is a tip-off that this is a “tale with a point of view.”

The ancient Greeks were one of the originators of the “tall tale” that conquered peoples were “barbarians” who needed to be taught by “civilized human beings.” How can we tell a “barbarian” from a “civilized human being”? The Greeks had a simple answer to this question. “Barbarians” have weird sexual appetities and worse, they sacrifice and eat other humans. Sadly, this “tall tale” continues to be re-told up to the present day in order to justify conquest. (Who among us has not seen the movies and cartoons in which “half-naked” “natives” cook up other humans in stew pots?)

Where did the monster known as the Minotaur come from? Here the Greeks tell another “tall tale.” The Minotaur was the product of the “weird sexual appetites” of Queen Pasiphae. Like her daughter Ariadne, “Queen” Pasiphae was no heroine. Rather, she was cast in the role of ancient Cretan “porn star.”

According to the tale told by the Greeks, Pasiphae, like her daughter, “fell in love”—but in her case, not with a Greek hero. Pasiphae not only loved a bull, she lusted after it and desired to “mate” with it. The fantasy of women mating with large animals (with large “members”) is the stuff of pornography up to the present day.

Pasiphae’s “lust” for her bull incited her to engage the engineer Daedalus (of Icarus and Daedalus fame) to create a mechanical contraption that would enable her to mate with the bull. The result of this folly was a monster child—the Minotaur. As soon as she gave birth to him, Pasiphae abandoned her monster child in a cave where he grew up and began demanding human sacrifice.

The “tall tale” told by the Greeks about ancient Crete was concocted to “prove the point” that the ancient Cretans were barbarians. The weird sexual appetites of a “barbarian Queen” produced “a monster” who demanded the unthinkable—“human sacrifice.” Ipso facto—conquest was necessary and justified in order to save “the barbarians” from themselves.

How might the ancient Cretans themselves have told these stories?

How might the ancient Cretans themselves have told these stories?

In the Greek story, Pasiphae is a twisted “Queen” in an ancient Crete imagined to have been ruled by her husband “King Minos.” But there is no convincing evidence that there ever was a King or a Queen in Crete before it was conquered by the Greek-speaking Mycenaeans. What if ancient Crete was a matriarchal culture in which grandmothers and their brothers created “participatory democracy” where there was no hierarchy of the sort that produces Kings and Queens? I have discussed egalitarian matriarchy (which is not the opposite of patriarchy) in an earlier blog. In ancient Crete the cave was not a place where fearful monsters dwelt. Rather, caves were understood to be the womb of Mother Earth, a place of birth, rebirth, and transformation.

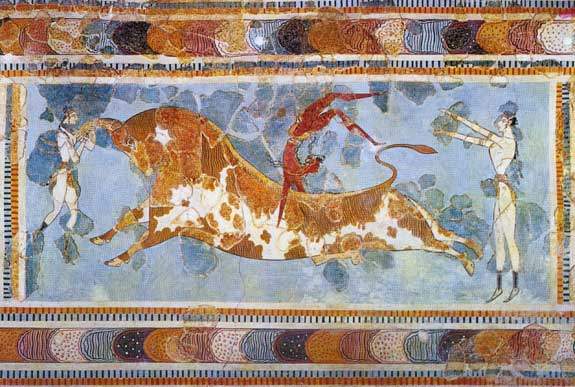

Ancient Cretan art suggests that bull-leaping games were an important part of Cretan rituals. The major excavator of Knossos believed that both boys and girls participated in it. Could the memory of this have led to the notion that both boys and girls were sacrificed to the Minotaur?

It is often said that bull-leaping was a dangerous game and that the bull was sacrificed, but I imagine a different scenario. What if bull-leaping was a sort of “4-H” project in which young teen-agers raised bulls and trained them to play leaping and dancing games? The children who performed acrobatic feats with their pet bulls, would of course have loved them, but such love would have had nothing at all to do with lust.

Such a bull, as I imagine the story, would not have been sacrificed or eaten, but would have been set out to pasture after the games. He would have been prized for his “gentle” qualities and tameness and would have been allowed to sire other bull calves to take part in future games.

Ariadne may have been the name of one of the girls who took part in the bull games. Perhaps her name was remembered because she was the most agile and graceful of the leapers and dancers in the rituals with the bulls.

Here we can see how patriarchal cultures transform the symbols of earlier cultures and distort their meaning in order to drain the power from them. In so-doing they justify their conquest and make their domination of other peoples seem right and reasonable. In time, even the conquered and dominated come to believe that the myths told by the victors contain “eternal truths.” No more!

An earlier version of this piece was published with different format on Pagan Square/SageWoman Blogs.

Readers of this post might want to share Selene: The Most Famous Bull-leaper on Earth by Z. Budapest with the girls in their lives.

Carol P. Christ is looking forward to the spring Goddess Pilgrimage to Crete which she leads through Ariadne Institute. Early bird special for the spring pilgrimage extended for those who join now. Carol can be heard on a WATER Teleconference. Carol is a founding mother in feminism and religion and women’s spirituality. Her books include She Who Changes and Rebirth of the Goddess and the widely-used anthologies Womanspirit Rising and Weaving the Visions. In college and graduate school she was taught to discount her gut feeling that “there was something wrong” with the stories and myths she was told contained “profound truths” if she wanted to be considered “intelligent.”

Reblogged this on Human Relationships.

LikeLike

Carol, thank you for your wisdom and for sharing this myth, and how ancient customs have been twisted by the Mycenaeans. It’s fascinating, and shocking to see how matriarchal societies were – and are – regarded as threatening by most ‘civilised’ people.

It reminded me of the bull-jumping ceremony of the Ethiopian Hamer tribe, which is centuries old. Here are some very good images and a woman traveller’s report.

http://newflowerethiopia.wordpress.com/2013/02/10/bull-jumping-ceremony/

Here again, the women insist on being humiliated – in the form of whipping. Why, oh why?

LikeLike

I just went to the site you suggested and was surprised that the(boys’) initiation ceremony includes whipping of the women. Not exactly what I was expecting given Carol’s post.

LikeLike

Beautiful post, Carol. Do you remember Mary Renault’s novels The King Must Die and The Bull from the Sea? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Renault I read them as a young girl and most likely they were slanted towards Theseus. What stays with me is her description of the bull-dancing and the trust and camaraderie between the young dancers. I can remember wishing (as a thirteen year old) that I could be a bull dancer. Just wondered if you had read those novels, too.

LikeLike

Elizabeth, I did read them but when I was old enough to be critical. I don’t remember the part about the bull-leaping, but maybe I will reread one day.

LikeLike

Brava for your wise deconstruction and reconstruction. Another way the Greeks labeled non-Greeks was to call them “barbarians” because they didn’t speak proper Greek but barked like dogs, “bar-bar-bar-bar.” Yes, my name comes from the word, and at age seven or thereabouts, when I looked it up in my grandfather’s dictionary, I found this definition: “strange, foreign, different.” That is no doubt how Theseus and the other Greeks saw Ariadne and other prepatriarchal goddesses and their people. Distortion even of earlier people’s languages.

LikeLike

This was the first year that women were allowed to do ski jumps in the Sochi Winter Olympics, and that’s what came to mind here, it was wonderful to see how good they were, literally flying through the air effortlessly, landing perfectly, as if they had been doing it for a long time and I guess maybe that’s the case. Anyway a break through, for re-incarnted bull leapers maybe, who knows ((-:

LikeLike

I also think of the girl-women gymnasts as being like the bull-leapers.

LikeLike

A wonderful deconstruction and (speculative) reconstruction of the Ariadne myth. The person I turn to for understanding pre-Greek Cretan culture is Lucy Goodison. She has done meticulous research into this period. She speculates with Martin Nilsson that Ariadne may have been a sun or vegetation goddess, specifically a death/rebirth figure, since Her death predominates in the myths and artifacts that come down to us. She also notes that there was a Cretan goddess named Dapuritojo, meaning Lady of the Labyrinth. So I think we could speculate that perhaps Ariadne was a goddess in the pre-Greek pantheon of Crete, perhaps the Goddess of the Labyrinth, who seasonally enacts the death and rebirth of life on the island.

Goodison also shows in her work that the early Cretans probably lived communally, didn’t seem to have special grave goods for specific (hierarchically superior) persons, lived without military fortificaitons, So I think your statements about matriarchal culture in early Crete are right on!

LikeLike

Nancy thanks for mentioning Goodison. I use her work too. Feminist archaeological analysis of Crete is thin on the ground.

LikeLike

when I look at the symbolism in early Cretan art and ritual it never ceases to amaze me how cautionary tales of Greek myth and legend retained the early symbols of bulls, bucrania, snakes, blood, pillars, columns and labyrinths/cave/adyton. When placed in conquest and odyssey type stories their meanings change so that what appears to be women focussed symbols are turned against as. With out the oppositional stance, contest or agon one wonders what other types of narrative could emerge.

LikeLike

Well said! Thank you!

LikeLike