“The error of anthropomorphism” is defined as the fallacy of attributing human or human-like qualities to divinity. Recent conversations with friends have provoked me to ask in what sense anthropomorphism is an error.

“The error of anthropomorphism” is defined as the fallacy of attributing human or human-like qualities to divinity. Recent conversations with friends have provoked me to ask in what sense anthropomorphism is an error.

The Greek philosophers may have been the first to name anthropomorphism as a philosophical error in thinking about God. Embarrassed by stories of the exploits of Zeus and other Gods and Goddesses, they drew a distinction between myth, which they considered to be fanciful and false, and the true understanding of divinity provided by rational contemplation or philosophical thought. For Plato “God” was the self-sufficient transcendent One who had no body and was not constituted by relationship to anything. For Aristotle, God was the unmoved mover.

Jewish and Christian theologians adopted the distinction between mythical and philosophical thinking in order to explain or explain away the contradictions they perceived between the portrayal of God in the Bible and their own philosophical understandings of divine power. While some philosophers would have preferred to abolish myth, Jewish and Christian thinkers could not do away with the Bible nor did they wish to prohibit its use in liturgy.

Thus theologians developed the method of allegorical interpretation in which the anthropomorphism of the Bible was understood to symbolize higher truth. Thus, God did not really “walk” in the Garden of Eden, nor did God actually “get angry” with his people; the higher truth embedded in these tropes had to do with the love of God for the world. For some theologians even the notion of God’s love for the world had to be qualified by asserting that this “love” was dispassionate and implied no “need” the part of God for the world.

When my theological companion Judith Plaskow and I began to discuss our understandings of Goddess and God with each other, it became clear that one of our main differences was about whether or not it makes sense to think of God or Goddess as a kind of “person” who can and does “care about” and “love” the world. Judith invoked traditional notions of the anthropomorphic fallacy to defend her notion that God is an impersonal power of creativity that is the ground of being. She criticized my notion of a Goddess or God defined by a relationship of care, compassion, and love for the world as anthropomorphic.

In response to Judith, I defended anthropomorphism. I argued that if we value love and understanding in ourselves, then it makes sense that we “attribute” these “personal” qualities to divinity and “find” them in the divinity we know through our experience.

I find philosophical support for my experience of divinity as a power or presence that loves and understands me and all other beings in the world in the relational philosophy of Charles Hartshorne. Hartshorne considered the (western) philosophical and theological tradition’s notion that God is dispassionate (without feeling) and has no need for this or any other world to be the height of theological folly.

He argued in contrast that God should be understood to be the most relational of all relational individuals, the most feeling of all feeling individuals, and the most loving of all loving individuals. Such a divinity is defined by relationship to the world, and its relationship to the world is best understood as love and understanding, encompassed in Hartshorne’s notion of “divine sympathy” (or empathy) for the world.

So—I responded to Judith–if experiencing divine “feelings” for the world and attributing consciousness feeling for the world to deity constitutes “anthropomorphism,” I affirm anthropomorphism and do not consider it a fallacy.

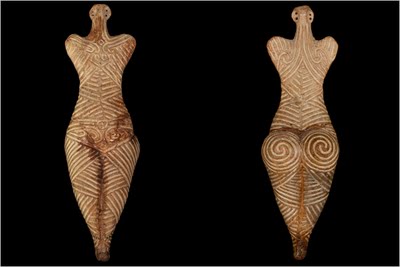

At the same time, I do not view Goddess as “really” having a human-like body, such as the ones portrayed in Greek statues, or even such as the ones portrayed in feminist art. In fact, the only images of Goddess that resonate with me are those in which she takes animal and plant as well as human forms. For me the world is the body of the Goddess.

Recently a friend commented to me that she found her new Buddhist practice liberating because it did not require her to “visualize the Goddess” in female (or any other) form. In addition, she stated, in her Buddhist practice she had stopped “asking the Goddess for things.” This conversation provoked me to rethink my earlier “affirmation” of anthropomorphism—and will no doubt lead to revisions of the book manuscript.

Although I have Goddess “figurines” in my home—mainly the early part-human, part-animal ones, my “practice” has never involved “visualizing” a female Goddess and then praying to her. As I said to my friend, I “feel”and “sense” the Goddess rather than “seeing” her. For me the presence of the Goddess is a feeling–that I sometimes sense entering through the pores of my skin–of a loving presence that cares about me and about every other individual in the world.

I do in fact sometimes experience this presence in places that have been considered sacred by others, such as caves and mountains in Crete, and I also have experienced it in the icons of the Panagia (Mary Mother of God) at sacred places in Crete. But I do not privilege visualizations of the divine presence in the human form. I also experience daily “the grace of Goddess” in the birds that bathe in my fountain and in the butterflies and bees that fly in my garden.

There was a time when I prayed to the Goddess intensely “for things”—for a lover, for my Greek citizenship, for the success of our Goddess pilgrimages. I was often disappointed when I did not receive what I asked for. This has led me to change the form of my practice of prayer. Now I am more likely simply to ask the Goddess to be with me in all that I do and in times of need—rather than to ask for specific outcomes.

I conclude from this that it is important to distinguish at least two different meanings of “anthropomorphism.” If anthropomorphism means that divinity has a specific human-like (female, male, or inter- or transgender) physical form, then I would agree that it is an error to be avoided.

However, if anthropomorphism means that deity has human-like (and animal-like and plant-like and mineral-like) consciousness and feelings, then I would argue that this second form of “anthropomorphism” is not an error.

I would add that when we pray to a Goddess or God who cares about the world, we should not assume that all of our prayers “for things” can or will be answered. The kind of “answer” to my prayers I now find most meaningful is the experience of divine presence in the world, in myself, and in all others. She is the grace of life in me, and She is with me in all that I do, loving and understanding me as no one else can, always inspiring me to love and understand the world and all of the individuals in it more.

Carol P. Christ will be leaving in a few days on the spring Goddess Pilgrimage to Crete which she leads through Ariadne Institute–early bird special for the fall tour until June 15. Carol can be heard in a recent interviews on Goddess Alive Radio and Voices of Women. Carol is a founding mother in feminism and religion and women’s spirituality. Her books include She Who Changes and Rebirth of the Goddess and the widely-used anthologies Womanspirit Rising and Weaving the Visions. Follow GoddessCrete on Twitter.

Great post Carol, thank you! I have long understood humanity to be god/dess makers. All over the world in different places people have, since time immemorial, created deities that reflect the properties of their surroundings and themselves. Seeing god or goddess personified in human form is a natural product of this process, but like you, I also see the earth as the body of goddess. I wish I could attach an image here of the paintings I did inscribing the goddess markings from the back/front figurines in your post onto a female body… the earth inscribed on her body…

LikeLike

Great topic and essay, Carol. Vincent Van Gogh, the famous Dutch painter, thought of God as a painter–just as he (Vincent) was. In his letters to Theo (his brother), when thinking about injustice, noted that the world was one of God’s “studies” that just didn’t come off right. It may have been one of God’s bad days. Point being–we humans understand the divine or the spiritual through the prism of our experience, as Majak has said. Thanks for writing.

LikeLike

A very tender, and inspirational sharing, thanks so much, Carol!! To me, the gods and goddesses are all the individuals we love (including friends, family, colleagues, coaches, cats, dogs, etc) — they have so much power over us, just because we love them and likewise they are filled with beauty and grace, no matter their age or attractiveness. We wait on their every word, because we are alert to their thoughts, their insights. Like the Greek gods, we seek to placate and appease them, because we hope for love in return.

Jesus also says in the Gospels, “Ye are all gods.” And that is basically the teaching of Zen Buddhism, that we all possess Buddha Nature, whether we know it or not. An alley cat has it too, and every tree, or flower, or rock, or even a picket fence. HOORAY!!

LikeLike

I suppose I am making a stronger statement than…we think of God through our experience. I am saying that to the best of my knowledge and ability to think…God or Goddess IS a conscious feeling individual.

LikeLike

Brava! Of course we also anthropomorphize animals, too. Bambi. Thumper. The animals that live with us. I like to consider gods and goddesses as embodied but also as forces and consciousness.

LikeLike

Or is it that they really are little “fur persons” to quote Doris Lessing? Hee hee…

LikeLike

Thank you for this succinct and beautiful post!

LikeLike

The christian god’s posited complete lack of actual need or love for us feeds nicely into the conceptualization of a patriarchal family’s dominating father who can be terrifyingly cruel or absent — but justify this behavior by stating he’s doing it for your own good. However, every study I’ve read clearly demonstrates that social and cognitive development for human beings (which I perhaps naively presume is one of the goals of spirituality) occurs less within a coldly impersonal power paradigm, and more in being present for each other: touching, caring, and loving. Harry Harlow’s (rather horrible, in retrospect) studies on dependency in monkeys was just the beginning of this understanding regarding the importance of nurturing companionship: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Harlow.

Recently I’ve also started working on my gratitude by offering thanks before each meal. Initially I started out thanking the Goddess for the sources of the food on my plate, the soil and rain and sun and plants which sustained it, the humans that grew and harvested it, and that transported it to the local store and sold it to me. However, while reading your post here I came to the curious realization that I’ve also been referring to Goddess as all these blessings as well. I think that is how I prefer to think of Her: as lovingly incarnate within all the elements which go into the make-up of the cycle of life itself. Am I understanding correctly that this is somewhat akin to what you are describing?

LikeLike

Hi Collie, Gratitude is my practice too. Technically speaking my view is panentheism, which I understand to mean that divinity is “in” the world, “in” everything, and also a consciousness that holds is more than the sum of the parts.

LikeLike

Thank you for this post; you help me to understand my own perceptions of Divine through the reflections elicited by your sharing of your journey. Sadhana for me has become primarily devotion and gratitude rather than, as you and others have commented, asking for particulars. For me, Goddess has no limitations other than my human ones imposed upon Her.

LikeLike

In my view, Goddess does not have all the power because other individuals including me and thee have real power to affect the world. From the point of view of many traditional theologies the power of Goddess is “limited” by the real power that other individuals have. Some theologies state that Goddess “chose” to limit her power so that others could exist. I prefer to think that Goddess always exists in a relational world and therefore that her power is not “unlimited.” This explains why she could not stop the slave traders in their tracks…and many other things.

LikeLike

Hi Carol —

Thanks for this provocative post. As usual, I love the historical framework which you begin with. It helps all of us understand ideas that just seem like “common sense,” but actually are historically enculturated.

I have two responses to your distinction between visualizing Goddess in a human-like form rather than experiencing Her as having “human-like (and animal-like and plant-like and mineral-like) consciousness and feelings.” The first is that you are distinguishing between a visual form of connecting with the Goddess and a kinesthetic form. I believe that for some people visualization of a human form for the Goddess is the best way to connect with Her. Some people are visual when it comes to their most profound experiences, unlike you and I, who find our greatest profundity in the kinesthetic, i.e. feeling the Goddess as a presence in our lives. One of Tibetan Buddhism’s main practices is the visualization of the thousand-armed Tara in all Her detail in order to connect with Her love and compassion. (Then, of course, there are those who connect with the Goddess through their auditory sense).

Secondly, like you, I prefer the image of Goddess as including the entire body of the world (or even universe). But I believe that for us as humans, story is one of the main ways that we connect in our lives. And the stories we tell involve people, by and large. Even to FEEL connected to the Goddess, I believe that stories/myts of our Goddesses as actors who are imaged as human can be very helpful. I think of the Demeter/Persephone myth which often informs my life. The problem lies with the patriarchal Greeks — whose influence is felt to this day in our philosophies and theologies — as you note, who drew “a distinction between myth, which they considered to be fanciful and false, and the true understanding of divinity provided by rational contemplation or philosophical thought.” We aren’t just rational beings. We’re emotional and relational beings, and story helps us to connect.

Of course, we’re “god-makers.” Of course, our god-making limits our imaginations re: the ineffable reality of the divine. But that’s who we are. If we remember both our limitations and realize how we as individuals personally connect to what’s beyond us, then we have the best of both worlds. In fact, although I agree intellectually with Judith Plaskow that Goddess is “an impersonal power of creativity that is the ground of being,” my emotional make-up makes it necessary to be in a personal relationship with Her. Inconsistent? Sure is! Useful? You betcha! And when it comes to religion, I believe it’s a psycho-spiritual path that each of us needs to navigate as best she can.

LikeLike

I agree with you that some are more visual, some more auditory, some feel, and some sense through their skins. I am visual too, I see the Goddess in everything, though I don’t visualize her while praying with my eyes closed. But there are different paths for sure.

Judith would agree with you that we need anthropomorphic imagery. However she would disagree with me that this imagery means that God really is a kind of a person who cares about the world.

As for stories, I guess I think we need new ones. I am not much moved by the old ones if they include Gods who rape or hold swords and spears. I do like Demeter and Persephone, esp. as retold by Spretnak. I also like aspects of the Innana story, but not all of it. Perhaps we need to tell new stories, as we are doing about our relation with the power we call divine. These stories would not be about Gods and other Gods or Gods and Demons, but rather about our own serpentine paths to understanding the divine in the world.

LikeLike

Very nice post. Sometimes I ask God to just be with me and guide me to the right choices.

My favorite ‘definition’ of God was from the movie, “Jeffrey” where Father Dan explains: You know as a kid when you play that game in a circle and everyone is hitting a balloon around but at the same time they are trying to keep the balloon from hitting the floor? Well, that’s how God is.”

LikeLike

I believe that humans invented gods/goddesses to explain things they didn’t understand and as substitutes for parents who were imperfect – a kind of wish for someone/something to be in control, since we are painfully aware that we are NOT in control, of anything at all. Those who suffer most are often the ones who cry out for help from an unseen power. It is very difficult to face life with the knowledge that there is no “big daddy or mommy in the sky” who is in charge, who loves us and will take care of us, but in my mind, making up a story doesn’t solve the ultimate problem of suffering and death (which are the bottom line issues that religion struggles with). I guess I’m kind of an existentialist – I see that life has no inherent meaning, and the only meaning it will have for me is the meaning I give it. At this point in my life, it seems to me that the only point in living is to help those who are worse off than myself. I do try, while also keeping in mind that my imperfect efforts may possibly cause more harm than good. Talking with others who struggle to figure out the best way to use our time on earth – especially at my UU fellowship – works better for me than prayers to an “imaginary friend.”

LikeLike

I revere the powers of birth, death, and renewal. I believe this cycle has inherent meaning. I define the meaning of life as including death, not as an escape from it. Judith would agree with you that I am praying to an “imaginary friend.” I beg to differ. However, I don’t believe this “friend” has all the power or is in control–rather she is (with Whitehead) a fellow-sufferer who understands and (with Hartshorne and others) love divine, all loves excelling. We do have different experiences, and I guess we will never all agree. However, my feeling that I am loved and understood no matter what — and that there is a power who loves and understands everyone and everything — is part of what keeps me going. Others including you and Judith have other ways. To tell you the truth, I have found communities–including sad to say both church and feminist ones–often fall short of offering support to all of their would-be members. That doesn’t mean I don’t need communities, but in my experience, it is better not to expect too much from them. Maybe it is too early in the morning and I need my coffee, but writing this makes me cry for some reason.

LikeLike

It is so difficult to recover from the lack of support once it has been experienced; perhaps it is because we expect so much from these groups once we find them. And we are so frequently disappointed.

I’ve often envisioned a matriarcal society where all women love and support and nurture each other. But the reality of it is that not all women are nurturing and supportive. Just as it is also true that many men are. And nurture and support are godlike qualities.

I feel the all encompassing LOVE of the Goddess as understanding, and encouragement, and the urging to find and use my own wisdom, my own gifts which are divinely given. She will be there to provide strength for the journey. She is in fact the journey.

LikeLike

“That doesn’t mean I don’t need communities, but in my experience, it is better not to expect too much from them. Maybe it is too early in the morning and I need my coffee, but writing this makes me cry for some reason.” You have touched the yearning in the hearts of many of us, and many of us shed a tear. Thank you for your extraordinary insight and beautiful post.

LikeLike

Love this!

In Vedanta, the divine can both be personal and impersonal – it depends on the needs of the seeker. God (or Goddess) being infinite means the divine can take any form that best suits us in that moment. Maybe someone in a moment of crises needs to call out to the Mother to feel her divine love and comfort, but then later is confronted by the cosmic, infinite, formless aspect of the divine. Both are needed and are true aspects of Mother.

LikeLike

Thanks, slimcrescentmoon! As you can see above, I, too, experience Goddess as both impersonal and personal. In fact, after I left my earlier comment, I realized that of course, the Goddess — the ineffable — could be both personal and impersonal. It’s our human limitations that try to categorize Her and put Her in a box. The more I learn about Hindu myth and philosophy, the more I’m attracted to it.

LikeLike

I’ve been reading She Who Changes and thinking about your take on anthropomorphism, and this article clarifies what I was wondering about, so thank you. As a pantheist, I find it hard to reconcile anthropomorphism of any kind with the divine. But I do understand everything in cosmos to be conscious on some level, and I agree with your philosophy of a compassionate, related and loving Goddess/God on that basis. But for me it’s more that human experience is inevitably a reflection of cosmos as a whole. And because we are relational, conscious beings, it follows that the divine is, too. I guess it’s a different way of arriving at a similar feeling!

LikeLike

Fascinating post and conversation. I agree with Nancy that different ways of understanding Goddess works for different folks. Just a few quick (I think) comments on what works for me: I think of the Universe as Goddess, not just the Earth ( e.g., the term “Earth-centered spirituality” is too limited for me and I prefer “nature-centered.) I sometimes think of Goddess as shared, participatory “power” among humans and the divine. This is related to another way of thinking of Goddess–as flow… Another way I understand Goddess is as a spiritual dimension (of the Universe or, as seems to be becoming likely, the Multiverses). Sometimes concrete figures representing specific Goddesses work to represent these for me (and are beautiful so trigger an aesthetic response), sometimes not.

LikeLike