The data came as somewhat of a shock to me. I stumbled across it one day in The Civilization of the Goddess, a mammoth book by the late Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas about what Gimbutas dubbed “Old Europe” – a culture area in southeastern Neolithic Europe that she maintains was centered around female deity.

Until she had the temerity to suggest that people at some point in the past might have worshipped goddesses rather than gods, Gimbutas had a sterling reputation among academics, even being hired to teach at two of the most prestigious of all American archaeology departments, Harvard’s and UCLA’s. After presenting her goddess theory of Old Europe, however, Gimbutas came under attack by a few powerful male archaeologists, after which her reputation among academics began to plummet (see Spretnak 2011 for a good accounting of Gimbutas’ fall from grace).

Before I get to the data that so startled me, I need to tell you a bit about archaeologists. Like the members of many academic disciplines, they disagree with each other – sometimes vehemently (and perhaps even somewhat more vehemently than scholars in other disciplines). One thing however they all agree on is this: the higher the quality and quantity of grave goods buried with an individual, the higher that individual’s status in her or his society.

Okay, now the data: Gimbutas presents a long list of Old European burial sites, almost all of which show that in Old Europe, those who were buried with quantities of high-quality grave goods – believe it or not – were old women and young girls. And sometimes even infant girls. Women in the mid-range of the age-spectrum were rarely if ever so honored, nor were men — of any age. I’d never heard of any other evidence like this before, nor had I ever expected to.

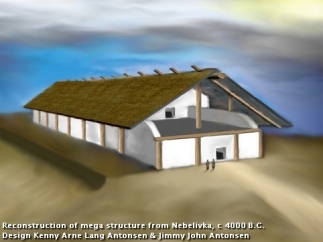

By now you must be a little curious about “Old Europe.” From roughly 6000 to 3500 BC. this ancient culture area covered what is today Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Hungary and Slovakia as well as parts of Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Ukraine, Albania, Greece and the former Yugoslavia. When it peaked around 4500 BC, says archaeologist David W. Anthony, “Old Europe was among the most sophisticated and technologically advanced places in the world” and was developing “many of the political, technological and ideological signs of civilization” (Wilford, 2009). Gimbutas’ insistence that Old Europe was goddess-oriented, is based to a great extent on the amazing numbers of female figurines unearthed there, many of them otherworldly. What’s more, Old Europe has produced few figurines or other artwork of males, otherworldly or otherwise.

Here are a few of Gimbutas’ examples of high-status Old European women’s burials (with a comment here and there about how the male graves contained either nothing or “only a few tools”):

In western Poland: four older women aged 50 to 70, and a man 50-55 were buried near a house. While the man had nothing in his grave, the women’s graves were filled with jewelry, beaded belts, vases, and other prized possessions.

“In the cemetery of Cernica at Bucharest … the richest grave out of 362 graves was of a girl about sixteen years old….”

Also in western Poland: “huge long barrows were raised” to bury one, lone woman. An example: “At Sarnaowo in Kujavia … a triangular barrow thirty meters long covered a central grave pit in which the bones of a woman about 70 years old were found. She was buried in a wooden coffin.”

In Old European cemeteries in western Hungary, “in addition to the great numbers of vases in female graves, the most exceptional graves … were those of girls and female infants. Boys’ graves were poor and adult and mature male graves were equipped rarely with more than one or several tools.”

“In the cemetery of Aszod, the most outstanding grave was that of a teen-age girl which contained a large temple model of clay with a bird’s head on top, standing on a human foot.”

“The graves of girls and female infants were consistently equipped with exceptional ritual objects not found in other graves.”

“The same pattern repeats in a number of [Old European] culture groups where cemeteries are known. Most frequently teen-age girls were either richly equipped with jewelry or included in their graves [were] items of exceptional ritual value” (Gimbutas 1991: 334-38).

To me, one mystery surrounding this amazing data is why no one has focused on it before (of course it could be that someone has and I just haven’t read them yet). This cemetery data provides incontrovertible evidence that female-ness was highly regarded in Old Europe – evidence no archaeologist could argue with. It also adds support to Gimbutas’ insistence that Old Europe was not a patriarchy and was not ruled by men, and also to her notion that the religions of Old Europe did indeed revolve around female, not male deity.

Gimbutas suggests that Old European women honored with loads of grave goods were either priestesses, or in the case of infant and young girls, members of a hereditary line of priestesses. This explanation however fails to explain why no women from the middle of the age spectrum appear among Gimbutas’ high-status females (any hereditary line of priestesses would, of course, contain women in the middle-age category). For quite some time this mystery perplexed me. It was only after sitting down to write this paper that one possible solution occurred to me: what sets the honored group apart is this: they don’t menstruate.

Unlike menstruating women, the honored women were holding on to their blood – which was no doubt deemed sacred, holy, and extremely powerful. Granted, teenage girls were sometimes part of the exalted group, but they could have been pre-menstrual. Of course I’m sure other possible solutions to the mystery exist. I’ll let you, dear readers, ponder the issue; maybe you’ll hit upon an even better solution than mine.

Sources Cited

Gimbutas, Marija. 1991. The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Spretnak, Charlene. 2011. “Anatomy of a Backlash: Concerning the Work of Marija Gimbutas.” The Institute of Archaeomythology, vol. 7, article 4. http://www.archaeomythology.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Spretnak-Journal-7.pdf. Accessed 3/17/14.

Wilford, John Noble. 2009. “A Lost European Culture, Pulled From Obscurity.” The New York Times, Nov. 30, 2009.

____________________

Jeri Studebaker is the author of Switching to Goddess and Breaking the Mother-Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years (forthcoming February 27, 2015). She has degrees in archaeology, anthropology and education, and lives in southern Maine.

I just received a book to review by two women archaeologists on Goddesses. They state, with reference to Cynthia Eller, who has no expertise in archaeology, that the theory of matriarchy and Goddess worship in prehistory has been disproved. Imagine that! I don’t know about you, but I think Gimbutas has a lot more expertise in the area than Eller, and furthermore that the proof or disproof of Gimbutas’s theories is complicated by deeply political issues, including the fact that Gimbutas disputes that patriarchy is universal and inevitable–a claim that cannot help but be deeply upsetting to many, especially those trained that patriarchies are the highest civilizations imaginable, which is everyone who went to college.

LikeLike

It’s unbelievable that any archaeologist would use Eller as a reference for anything about archaeology. I’m embarrassed for these two authors. If I remember correctly, Eller says that in order to write her Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory she was fed information by a male archaeologist friend of hers. If so, I wonder why the friend didn’t publish the book himself – or at least bill himself as second author?

As for the idea that patriarchies are the highest civilizations imaginable, some academics at least are admitting this just isn’t so. Archaeologists for example are now pointing out that the first “civilizations,” the first cities, were not in fact marvels of advancement but instead places of unimaginable misery: poverty, disease, slavery, hunger, and all of it presided over by a few elite males at the top — making sure everything stayed that way.

LikeLike

I am not able to evaluate how typical the examples you cite are, but I do note that Gimbutas often stated that grave goods in Old Europe were generally few and relatively equally distributed between male and female graves.

Just looked up that pages you cite and here is Gimbutas’s conclusion:”The most honored members of the Old European society were elder females, perhaps heads of the stem [clan]…Their graves do not indicate the accumulation of personal possessions, but are marked by symbolic items…” (CofG, 338)

It seems to me that Gimbutas is arguing that the women were honored because the social structure and symbol system was centered on the female clan, with leadership by the elder women. However she also notes that an equal number of male graves have grave goods suggesting that these men were “lead” traders. However, in neither case is there evidence of hierarchical class distinctions marked by the accumulation of vast treasure troves of private property.

Heide Goettner-Abendroth’s research on matriarchal societies corraborates these suggestions by Gimbutas, but it is important to recall (as Spretnak notes) that Gimbutas called these societies “matristic” rather than “matriarchal” in order to fend off the assumption that OE cultures were based on hierarchy and class divisions, as patriarchal societies are.

LikeLike

Yes, thanks, Carol, for bringing up this passage from Gimbutas:”The most honored members of the Old European society were elder females, perhaps heads of the stem [clan]…Their graves do not indicate the accumulation of personal possessions, but are marked by symbolic items…” I agree that Old Europe shows few if any signs of social stratification. I like to think that the Old Europeans perhaps functioned somewhat like The Minang of Southeast Asia. Peggy Reeves Sanday, who studied them, says the Minang aren’t ruled by men or women, but by adat matriarchaat, a set of rules based on nature and motherhood. What’s interesting about the data in my article, I think, is that the women honored were not mothers, but the women bracketing mothers on either side of the age spectrum.

LikeLike

Carol, in reply to your “I am not able to evaluate how typical the examples you cite are,” I believe Gimbutas is saying they are definitely the norm “in central and east-central Europe during the 5th millennium BC.” See page 338 in Civ. of The Goddess: In the context of talking about the comparative richness of the graves of older women and young girls (re: ritual objects), Gimbutas says that “The most honored members of the Old European society were elder females … and girls….”

LikeLike

Sorry to keep going, but child graves are close to the center of the communities, my speculation would be that it was hoped that the community would continue to “look after” the spirits of these children who never grew to adulthood, and perhaps also that the children’s young spirits would encourage “regeneration” and “rebirth” of life in the community.

LikeLike

That’s fine! I love your comments, Carol, and “the more the merrier.” What you say here makes perfect sense, and is very touching.

LikeLike

Great to see such a fascinating enigma shared at FAR. Thanks Jeri.

Here’s my take on it, just an idea. It’s possible that since the supreme deity in Old Europe was female, being born female may have meant you were destined for immortality. Maybe males were thought to return to this world and keep being reborn, until they chanced to incarnate themselves as females. If that were true, the males didn’t need the riches, because they weren’t making the crossing to the transcendent realm, but rather they needed help to keep re-birthing in Earthly existence symbolized by the earthly tools, buried with them.

P.S. I love that empty space between the two hands of the goddess figurine — infinite forms of liberation, openness, variations in ideas are suggested there.

LikeLike

What a fascinating and creative idea, Sarah! It’s one that never would have occurred to me, but it makes sense. Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing if the Old Europeans believed in reincarnation or not.

LikeLike

Most archaeologists are stymied about how the Neolithic package (domestication of plants and animals, rectangular buildings, living in villages, and pottery) spread so fast throughout Europe because migration patterns of people were much slower. My unproven theory is that the Neolithic package was spread by WOMEN. Women who knew the technology were married into hunter-gatherer tribes and taught their women, who were then married into other tribes, etc. As keepers and propagators of valuable technology, they would have naturally held esteemed positions in their society.

Not sure why the teen girls would have elaborate graves. Maybe their schoolfriends (why not have Neolithic package school for the girls?!) were mourning their departed classmate?

LikeLike

Your idea that plant and animal domestication was spread by women is a novel one. I’m wondering though how women would move from a sedentary lifestyle into a nomadic one. Would they do so by choice? I suppose they might in times of long-term drought, when and if their sedentary birth communities were falling apart. Parents in such communities might want to send their daughters out to the relative safety of groups that moved seasonally to where the food was.

As for teen girls, I’m not sure they’d be mourned any more than others in their societies (dead babies, children, dead spouses, grandfathers, etc.). My guess is, the nature of the goods deposited in graves in a society is something heavily determined by general cultural rules.

Keep coming up with your novel ideas!

LikeLike

I’m talking about the very early transition from hunter-gatherer (paleolithic +23,000 BC) into early agriculture & pastoral (neolithic 7000 BC). Women would move from a sedentary lifestyle into a nomadic one through religious conviction (ex. spread the technology/bounty of the goddess). The nomads would want to settle down because the sedentary people seem to be doing better versus nomads because the herds they follow are changing patterns due to climate change.

The transition from neolithic (Old Europe) into Bronze Age (Indo-European) would be much later (3000-2000 BC), and, according to Gimbutas and DNA evidence, come in waves.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing about Gimbutas and Old Europe. I think Carol’s comments are helpful additions to your post. One thing in your post I questioned as soon as I read it is the word “ruled” in your title. I don’t think Gimbutas would have used that word. Crones didn’t “rule” those towns.

It’s also interesting to remember that the horsemen, whom Gimbutas called Kurgans after the kinds of graves they built, who invaded and conquered Old Europe came from the Caucasus Mountains and the Russian steppes. To this day, there’s a lot of violence being exported from those areas, many of them with names ending in “-stan.” The Kurgans included that old serial rapist Zeus, who “married” a Great Goddess named Hera and demoted her to housewife. No, Greek mythology isn’t literal history. Some of it reflects what happened all over Old Europe.

I hope we’ll hear from you again.

LikeLike

You’re absolutely right to question the word “rule” in my title, Barbara. It was a bad choice of wording for an academic paper. I often write for popular periodicals and websites, and here I was using the word “rule” in the modern slang sense rather than the political one. As I replied to Carol above, I don’t think men *or* women in Old Europe “ruled” their communities in the political sense of the word.

As for the immigrants who brought an end to Old Europe, I believe there’s still some controversy about where they came from originally. The archaeologist Colin Renfrew thinks they came from Turkey. Geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza thinks that both Gimbutas and Renfrew are right, i.e., that “peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey.”

To me this is an important distinction. I’m working on a theory that connects long-term starvation with the rise of Indo-Europeans and the patriarchy in general. The Sahara and other deserts stretching across the Middle East and central Asia formed then, relatively rapidly, and I think many groups were caught in the middle of these rapidly expanding deserts, one of which covered Turkey.

LikeLike

My friend Miriam Dexter tells me that most linguists reject Renfrew’s theory in favor of Gimbutas’s. Spretnak also discusses this in the essay you cite.

Here is a link to an article that explains the DNA evidence which in general supports Gimbutas on the IE invasions.

http://www.eupedia.com/europe/Haplogroup_R1b_Y-DNA.shtml

A few years ago I wrote a blog on my father having the IE invader gene, R1b, the most common male dna in Europe. The reason for this is discussed in the linked essay.

LikeLike

Carol, this is a reply to your post: You’re right, most linguists do support the idea that the people who ended Old Europe were war-like, hierarchal people who spoke Proto-Indo-European and who came from the Pontic Steppe. Recent DNA evidence also seems to support this idea. However, I’m not so certain that the PIEs were war-like and hierarchical before around 4000 BC. I took the following from your Eupedia site: “The first clearly Proto-Indo-European culture was Sredny Stog (4600-3900 BCE), when small kurgan burials begin to appear, …. There is evidence of population blending from the variety of skull shapes. Towards the end of the 5th millennium, an elite starts to develop with cattle, horses and copper used as status symbols.”

I think that ca 4000 BC, small groups of people came to the Pontic Steppe from the south and “blended” with the PIE people. They came because at the end of the fifth millennium BC the “5.9 kilo year event” was turning 1/4th of the earth’s land surface into desert, and people were starving and dying by the thousands. I believe that some of the few who survived turned into the first war-like, hierarchical patriarchals. It wouldn’t take many of them to subjugate entire populations on the Pontic Steppe.

LikeLike

Could it be that the elder females had the richest grave goods because

they had the most descendants, still living, to ‘chip in’ for their after-life?

LikeLike

That could be, Heqat, but then why would the infant and young girls also have more grave goods than middle-aged women and most men? They’d have *no* descendants to contribute goods.

LikeLike

No, but they would have parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins etc., who could

have a sense of compensating for the interrupted life and thus, provide more grave

goods for the life that continues, beyond the grave, in which the infants/young girls

reach maturity.

Maybe they are provided with a dowry to attract a protector/partner/patron in the

afterlife? Middle-aged women may be seen to be joining their earthly husbands.

Do men need dowry goods?

Just throwing some ideas out there.

LikeLike

I like your idea that the infants and young girls needed protection in the afterlife. Another thing that ties the young and the old together is their greater need for protection compared to healthy young adults. Nice!

LikeLike

As it is the healthy young adults who are sent off to war to be maimed

or killed, I think their need for protection is far greater. But then, that

is a topic for another thread.

LikeLike

As an educated plebeian, humbly, may I adore you all? The accessibility of this article, intermingled with all the gentle, curious and informationally framed comments, combine and form a (perhaps ancient) sense of solidity in being – of remembering again. As I was reading I simply knew some of these communities were in Poland. My thanks.

LikeLike

It’s true, Shirley, part of the wonderful culture “Old Europe” existed in Poland. Are you (or your husband, children) of Polish descent?

LikeLike

Jeri, thank you for this wonderful article. I’m currently writing about the ancestral wisdom held in the blood which is accessed by the shaman, so it makes absolute sense to me that those who hold their blood would be honoured for their wisdom. Your article has also inspired me to revisit the subject of the Venus figurines, and wonder: in a society where young women are so idolised in the media, and old ladies are practically invisible, as is the case today, could it be that the Venus figurines are in fact cuddly grannies! They certainly have the figures for it!

LikeLike