I recently came back from a weeklong camping retreat for Christian faculty and their families in beautiful Catalina (an island an hour’s boat ride away from the Southern Californian mainland). This year’s conference theme was “Power Revealed: Gifts, Dangers, and Possibilities.” Not surprisingly, the topics of race, race relations, and institutional racism came-up repeatedly in sessions and informal conversations.

I recently came back from a weeklong camping retreat for Christian faculty and their families in beautiful Catalina (an island an hour’s boat ride away from the Southern Californian mainland). This year’s conference theme was “Power Revealed: Gifts, Dangers, and Possibilities.” Not surprisingly, the topics of race, race relations, and institutional racism came-up repeatedly in sessions and informal conversations.

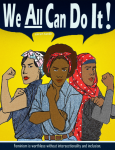

As they had last year, the conference organizers again provided an optional time/space for faculty women of color to gather together for a luncheon. Last year’s meeting (which I also attended) had been so successful that an assemblage of faculty women of color in the greater LA-area have been getting together periodically ever since for networking, mutual encouragement, and fun.

Without betraying the confidentiality of what was disclosed in our luncheon, something that surprised me was the ambivalence that a few attendees expressed about the very term “women of color.”

I also became privy to some confusion—and even discomfort—that some other folks (outside of the luncheon) felt about the term. For example, one Asian American woman had not thought that the term “women of color” included her since she had assumed that the phrase was simply the newest (perhaps politically correct?) way of referring to black or African American women. And one white guy told me that he had long found the phrase “[X] of color” (e.g., “communities of color,” “people of color”) odd, because wasn’t it simply a reversal of the antiquated and maligned term “colored people”?

The ambivalence, confusion, and discomfort I encountered at the conference about “women of color” was something I hadn’t anticipated. For in the academic and professor circles I frequent, the descriptor “[X] of color” is commonly used without comment (e.g., I’m on the steering committee of the Women of Color Scholarship, Teaching, and Activism group of my professional organization and arguably the most-respected leadership/professional development organization for Christian ministers and scholars in my field provides substantial grant and fellowship opportunities for students “of color,” by which they mean persons of African, Latino/a, Asian, and First Nations descent.)

I have since done a quick internet search to see if the hints of dissonance I heard at the conference were echoed elsewhere. Sure enough, questioning the purpose, scope, and desirability of the term is a “thing.”

Here are three examples:

- DiversityInc’s popular “Ask the White Guy” column has provided a response to the question “Is ‘People of Color’ Offensive?” (Short answer: no, “it’s a respectful-sounding phrase…in common use” that is reminiscent of “Dr. Martin Luther King[‘s] us[e] [of] the phrase ‘citizens of color’ in his 1963 ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech”).

- The NPR program “Code Switch” did a piece a few years back entitled “Feminism and Race: Just Who Counts as a ‘Woman of Color’”? (Short answer: the term is inclusive of Asians and Latinas, among others).

- The feminist digital media site Everyday Feminism recently introduced a video clip (reproduced below) about the origins of “women of color” with this lead-in: “Have you ever wondered where the term ‘women of color’ came from? Have you mistakenly assumed that it was created by white people? Are you unsure about how you feel about it?”

I was heartened to see several sites pointing to well-known human rights and feminist activist Loretta Ross’s mini-history lesson of how the term came to be. Methinks the three minutes it’ll take to watch it will be well worth your time.

For those wanting these ideas to simmer, gratefully Andrea (AJ) Plaid of Racialicious, has provided a transcript:

Loretta Ross: Y’all know where the term “women of color” came from? Who can say that? See, we’re bad at transmitting history.

In 1977, a group of Black women from Washington, DC, went to the National Women’s Conference, that [former President] Jimmy Carter gave $5 million to have as part of the World Decade for Women. There was a conference in Houston, TX.

This group of Black women carried into that conference something called “The Black Women’s Agenda” because the organizers of the conference—Bella Abzug, Ellie Smeal, and what have you—had put together a three-page “Minority Women’s Plank” in a 200-page document that these Black women thought was somewhat inadequate.

(Giggles in background)

So they actually formed a group called Black Women’s Agenda to come [sic] to Houston with a Black women’s plan of action that they wanted the delegates to vote to substitute for the “Minority Women’s Plank that was in the proposed plan of action.

Well, a funny thing happened in Houston: when they took the Black Women’s Agenda to Houston, then all the rest of the “minority” women of color wanted to be included in the “Black Women’s Agenda.” Okay?

Well, [the Black women] agreed…but you could no longer call it the “Black Women’s Agenda.” And it was in those negotiations in Houston [that] the term “women of color” was created. Okay?

And they didn’t see it as a biological designation—you’re born Asian, you’re born Black, you’re born African American, whatever—but it is a solidarity definition, a commitment to work in collaboration with other oppressed women of color who have been “minoritized.”

Now, what’s happened in the 30 years since then is that people see it as biology now.

(Murmurs of understanding, agreement)

You know? Like, “Okay…” And people are saying they don’t want to be defined as a woman of color: “I am Black, “I am Asian American”…and that’s fine. But why are you reducing a political designation to a biological destiny?

(Murmurs of agreement)

That’s what white supremacy wants you to do. And I think it’s a setback when we disintegrate as people of color around primitive ethnic claiming. Yes, we are Asian American, Native American, whatever, but the point is, when you choose to work with other people who are minoritized by oppression, you’ve lifted yourself out of that basic identity into another political being and another political space. And, unfortunately, so many times, people of color hear the term “people of color” from other white people that [PoCs] think white people created it instead of understanding that we self-named ourselves. This is term that has a lot of power for us.

But we’ve done a poor-ass job of communicating that history so that people understand that power.

Thank you, Loretta Ross! I am constantly learning from you! While I didn’t before know this birthing story, I have long intuited Ross’s basic point that the term “women of color” is political, not merely factual. In using and self-identifying with this term, we women of color need not assume that our stories are the same (since they aren’t). Instead, we can willfully employ it in solidarity with others who live and struggle and move embodied in the world at the intersections of gender and race, along other factors (e.g., class, religion, sexuality/marital status).

Did you previously know the origins of the term “women of color” (or, like me, are you just now learning about this particular moment in history)? What now do you think of it? If the term still unsettles you, would you care to explain why and what might you offer in its stead? If you support the (continued) use of this term, how can we do better than a “poor-ass job” of communicating its history and intended (activist) meaning?

Grace Yia-Hei Kao is Associate Professor of Ethics and Co-Director of the Center for Sexuality, Gender, and Religion at Claremont School of Theology. She is the author of Grounding Human Rights in a Pluralist World (Georgetown University Press, 2011) and co-editor (with Ilsup Ahn) of Asian American Christian Ethics (Baylor University Press, 2015-forthcoming). She especially cherishes her friendships with her two faculty women of color colleagues (pictured below).

Thank you, Grace. Your post is very informative. I appreciate you taking the question and exploring it in this way.

With Gratitude,

Marcia

LikeLike

Thanks Marcia for taking the time to offer an affirmation! :)

LikeLike

Maybe the phrase needs to be expanded to Women of Color United for Change. It then could become an accepted acronym, such as WCUC

LikeLike

Bernadette – I appreciate the point. Your “United for Change” part would make the intention of “women of color” explicit. As I understand it, there’s no shortage of acronyms for WOC groups (e.g., WOCA stands for Women of Color in the Arts).

LikeLike

Thanks Grace. I don’t think the expression, “people of color” is offensive. The bottom line is that we all know what the term refers to, and that it is highly respectful of diversity within the context of equality. And so there’s no need to change anything. Language can be twisted in a thousand ways to criticize things, that is, if someone is determined to go negative and make a fuss.

LikeLike

ABsolutely it bothers me; in fact it saddens me that our thinking is so shallow. To me, the term underlines our on-going prejudice. Women are women; that”s it. !!!!!!!!!!To distinguish any person according to any part of their body is insulting, demeaning and negative.

LikeLike

Mary – I’m wondering if you viewed/read Loretta Ross’s explanation of the origins of the term. If I interpret your comments most charitably, you don’t like the idea of dividing women (as a whole) into sub-categories based on other distinguishing features. I can appreciate the concern, but surely you could imagine someone saying something similar about the term “women” – why divide humanity into two (or even more) sexes or genders? Why not just speak of humans? The point is that generalizing in these ways can be illuminating, though we must always be mindful of the ways that categorization helps — and potentially hurts.

LikeLike

Sarah – thanks for taking the time to respond and I agree with you – the term “women of color” already has significant traction. I’d vote for educating us all more (myself included) than changing the helpful term!

LikeLike

The term women of color never has made me uncomfortable, but I am delighted to know its history, that it is a self-naming with a political purpose. Right on, write on!

LikeLike

Elizabeth – thanks for your affirmation; I just might “steal” it from you as I comment on well-written student activist papers (“right on, write on”)!

LikeLike

It seems to me that any acceptable term which unites women from non-white backgrounds is a good thing. Too often people from various non-white backgrounds oppress each other rather than joining together which is exactly what certain white male powers want them to do. I am glad I now know the origin of the term.

LikeLike

I could have phrased the above more effectively–the “powers” want division not unity.

LikeLike

Juliana – I appreciate these sentiments so much. All who are steeped in feminist history know what patriarchal systems have done, so either “white male powers” or “the powers” would be appropriate (since we are not talking about individual acts of discrimination but structural oppression).

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this post. I appreciate the greater understanding of the origin of the term as well as a better sense of what it signifies for you. At the same time, I have had a sincere question about the designation “people of color” for a number of years, but have been afraid to raise it for fear of coming of as insensitive. I am also new to this forum and have been pleased by the thoughtfulness and kindness exhibited throughout the discourse. So, I would like to voice my question here.

By way of self-disclosure I am a Jewish man who readily passes as white. I continue to wrestle with the intersections of my own experience of privilege and othering. I know I have more to learn and grow, so I ask this question in hopes of deepening my understanding.

My question about the phrases “people of color” or “women of color” is: Doesn’t it implicitly accept the normative status of Euro-American or “white” as people without color? What I mean is, if only those who represent a minority in our society are said to be “of color” then does it allow the majority to see themselves as without color? Perhaps a good analogy might be that I don’t have an accent, but anyone who speaks differently than me has an accent. I understand the primary focus of the term is political, encouraging solidarity, and not related to biology or skin color, but perhaps the difficulty in communicating that effectively relates to the phrase itself referring to the external characteristic of color. I was drawn Loretta Ross’ description of those who have been “minoritized”. I like this (better than minority) because it recognizes the active quality of exclusion and the dynamic nature of these relationships. Referring to minoritized communities seems to me to imply a greater expectation that change is possible.

As I write this, what arises within me is a comparison with the problem we have seen with majoritized people responding to Black Lives Matter with All Lives Matter as a way to evade the persistent issues that necessitated the Black Lives Matter movement. Do you see the phrase “People of Color” similarly? Does my proposal that it would be helpful if we all recognized ourselves as having color reflect a similar insensitivity to the experience of those who have been more strongly minoritized than I have? Or would we be better off using language that more directly describes the experience we want to describe so that we can continue to work to change the dynamics?

LikeLike

Russ – I appreciate your inquisitive spirit and very thoughtful reflection. Some of the points you raise (about normalizing one experience while inadvertently drawing attention/stigmatizing others) remind me of a blog I came across last night while composing my post – “Controversial Opinion Time: I Hate the Phrase ‘Person of Color'”, http://powderroom.kinja.com/controversial-opinion-time-i-hate-the-phrase-person-of-1634451508. And I think, given the contexts in which the phrases people of color/women of color originated, any “correction” that “we all have color” — even said with the best of intention — would rub folks the wrong way for precisely the analogous reason you described in the “all the matter” retort to the “black lives matter” movement (i.e., if the phrase “of color” is intended to unite different oppressed groups who are struggling in their own way against institutional racism and the structural privileging of whiteness, then any such “white people have color, too” would be read as negating or minimizing the racism that non-whites experience institutionally and personally).

Does that help? I wanted to add that I appreciate how your Jewish identity complicates your understanding of “whiteness.” As you know, many folks do not know how “whiteness” came to be (e.g., the Irish in America eventually “became” white but weren’t originally treated as such, as did Jewish folk, and there are some who speculate that Asians may eventually be regarded as white (since in some cases they are treated as “honorary whites”), while others insist that the perceived otherness of Asians is so strong that we as a group will always be regarded as the “perpetual foreigner”).

LikeLike

Grace, thank you for your response to my question. Thanks also for the link.

I appreciate that responding to a person claiming to be “of color” with “we all have color” would have the same effect of “all lives matter”. But what about in a conversation about what is the best way to describe/name/unite “different oppressed groups who are struggling in their own way against institutional racism”? Is color the best way to capture this experience and encourage inclusion of all struggling against institutional racism? It seems to me that continuing to focus on the symbolic uses of “white” as normative and “black” or “of color” as alternative and subversive (especially since, as you say, what these designate continues to change) could be replaced by more direct terms like “minoritized” (I can’t think of a good replacement for “white” at this point, “minoritizing”?).

LikeLike

Russ – I’m enjoying this continued engagement. There are a bunch of white scholars I know and respect who are actively involved in interrupting white privilege and in combatting racism (e.g., my colleagues Jennifer Harvey, Rebecca Todd Peters, and Cynthia Moe-Lobed come immediately to mind). To my knowledge, they are perfectly fine with being seen and labeled as “white” (since that is how they are perceived and they are aware of their privilege). Phrases like “people of color” of “women of color” shouldn’t be taken to imply that only they are — or should be — concerned about interrogating institutional whiteness.

Maybe an analogy would help. I am a straight ally to the LGBTQIA community. I don’t feel the need to label myself (or be labeled) as (also) “queer,” my advocacy comes from a different place than it would be if I were myself transgender or bisexual or lesbian, etc. And in campus (or other) events, I feel fine about the entire community of well-intentioned folk agitating for social justice on these issues being comprised of members of the LGBTQIA community + straight allies.

Does that help?

LikeLike

Thanks Grace. I am also appreciative of this continued interchange. It is certainly helpful for me to continue to reflect on my understanding and try to articulate ideas that have been wrestling inside me for a while. The link that you mentioned was also really helpful for me.

I appreciate your highlighting of the role of allies not needing to be included in the group the label is meant to delineate in order to join in the work against discrimination or domination. I am certainly invested in trying to be a better ally for people in the LGBTQIA community, for women, and for people of color. I try to take responsibility for the privilege that I have received because of my perceived “whiteness”. I can call myself “white” remaining cognizant of the symbolic meaning of that as part of the institutional racism in our society.

I guess my basic question is: While I thoroughly understand the importance and significance of a way of uniting the community of women (or people) who experience the othering “structural privileging of whiteness” in a collective term (recognizing the diversity within it), is there something powerful for you in calling this “of color” or is the term powerful for you because it has taken hold as the accepted way to address this group? Here I am not challenging your attachment to the term, but trying to understand the locus of the power in the term is for you. I hope that makes sense.

LikeLike

Russ – I totally get the question and your intentions behind it. My response is closer to your second option. As a feminist in the third-wave, I am not like the second- or first-wavers who had to create categories and institutions when none existed previously (e.g., I have always known a world in which feminist theology and journals dedicated to feminist scholarship existed). And so it is with the phrase “of color.” Frankly, I never experientially understood why society even thought to categorize in terms of color and named the colors as such (white, black, yellow, red, brown), since it didn’t seem literally true to me (e.g., many white people having reddish or bluish undertones). But these terms have their histories, which we know, and it’s important to honor the legacy of those who have done good work before us. Though it’s important to interrogate conventional understanding, it’s also important that we have common frames of reference, so that our words mean what others assume we mean by them. (Quick anecdote, I once heard of a clever medical school applicant who checked off the box “African American.” He had Egyptian heritage, so said in his defense that “African American” was literally true. But since “African American” means in common parlance, “those descended from slavery,” his use of “African American” obviously was intended to deceive. Not good.)

LikeLike

Thank you Grace. This is very helpful. I am grateful for your responsiveness to my questions.

LikeLike

Thank you for this post. I always disliked this term because I heard it as a catch-all for non-white people, which seemed somehow as if to say there are whites and then there is everyone else. Especially since I was ignorant of the origin, it sounded to me like a white-dominant term for “others.” I appreciate learning the origin of the term, although I still wonder if it advances an essentialist dualism of “white” and “color.” In any case, I am pleased to learn that it is a term of empowerment and an act of self-naming. Thanks so much again for sharing.

LikeLike

Natalie – thanks for your honest and candid reflections. As you (and others) have named, some of the discomfort that some feel lies in the concern about the creation (or continued support) of a binary. But I’m glad that learning the history and the intentions behind the coining of the term has done something to ease your dislike!

LikeLike

What a great post Grace! Working in politics, the power of naming and the power of reclaiming that “name,” “identity,” or “work” that one does is vital to the overall success of a community as well as the cause being fought for. I wish you would post more on this site (I know you’re extremely busy).

LikeLike

Thanks John for “getting it” and for all the good work you do. And, now that I’m back from sabbatical, I’ll indeed be blogging more here! :)

LikeLike

Thank G-d!

LikeLike

Thanks, Grace, for this mini-history. As a member of the 2nd wave of feminism, my experience with the term “women of color” was positive from the beginning, because I knew it was a term created by people of color. When I started to teach Women’s Studies in 1975 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I think the term we were using was “minority women.” I spent the entire year of 1977 in Germany and when I came back the term had changed to “women of color.” Since I’ve always appreciated self-naming as an act of power, it was easy for me to change over. But I never knew the actual history of the term. Thanks again.

Re: your conversation with Russ Arnold above, it seems to me that there are a variety of ways in which a white woman like myself can acknowledge her discomfort with the normative status of Euro-American or “white” people as people without color. I’ve been in conversations where people of color have pointed out that white is a color, too, as a way of pointing out this hegemony. It seems to me that it depends on the context (i.e. not always is this point of view analogous to “All LIves Matter.”)

LikeLike

Nancy – thanks for sharing your experiences with the term and for adding to the discussion I’ve had with Russ. Though I would put it differently, I get your larger point – it is not that non-whites “have” race while whites don’t — all races are (and have been) socially constructed categories and the powers that be have historically who’s in and who’s out for all sorts of purposes. :)

LikeLike

I visited this site because I’m a lifelong friend of Carol Christ (from college). Because of my age, I recall a different history to this phrase, particularly as it crept into the everyday vernacular. Demographers started observing that the U.S. would soon not be a majority white population about the same time that political activists started using the phrase “communities of color” (rather than “minorities”). It’s probably also a perspective extended from Jessie Jackson’s “rainbow coalition.” While the specific history you reported is interesting, I think the phrase caught on quickly more as a way to recognize both the importance of demographically no longer being in the minority; it was also a means for some people to assert that non-white racial groups have a shared experience. I personally think our experiences are far more nuanced than that, especially for groups that are closer to being immigrants as well.

LikeLike

Gail – thanks for sharing that history; it’s quite possible that there were multiple sources of origin (like the term “third wave feminism” as several independent sources).

LikeLike