The 2015 Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded in part to a Chinese woman (Tu) for her identification and isolation to treat malaria of a chemical known as Artemisinin. The name of that chemical derives from the fact that it is found in varying amounts in the ‘family’ (technically, genus) of plants known as Artemisia. The name of that family derives from its association with the goddess Artemis.

Because Tu’s work began in China in the 1960s it is understandable that even if she knew this about Artemisia (a term I use to refer to any one plant or all of the plants of that family) it would not have been a ‘careerbuilder’ for her to point it out to those for whom she was working. It was bad enough that she was a woman. At that place and time, however, if she had said or done something that could be associated with Western culture her name might not even be known today.

Nevertheless, because those awarding the Nobel Prize are free from discrimination or intimidation, it is startling that in the explanation provided for the award no mention is made of the Western legacy of Artemisia. To begin with, the very fact that the Prize was being awarded to a woman for a plant named after a goddess should have elicited at a sense of uncanniness that arguably deserved mention. Be that as it may, the failure to mention that Artemisia has a long history of being used medicinally in the West not only as an insect repellent but also to treat fever–a common symptom of malaria–is simply inexcusable.

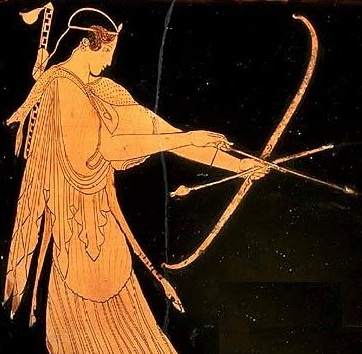

It is, however, not surprising. Notwithstanding that Artemisia was thought of in the ancient Hellenized world as a panacea, there should be little doubt that its relationship to Artemis and its use by women to treat health issues unique to women contributed to its marginalization and neglect by a medical profession dominated by men. The historical (and modern anecdotal) evidence would otherwise have attracted far more scientific scrutiny than it has to date. For it seems Artemisia, inter alia, (1) ameliorates symptoms related to menstruation and its cessation, (2) prevents conception, (3) induces abortion and (4) prevents, impedes or reverses the growth of cancer cells, especially breast cancer cells.

Moreover, thousands of years of usage–the ultimate ‘lab test’ Darwin particularly prized–both medicinally and for culinary purposes indicate there to be no substantive risks in doing so. Indeed, the very fact that Artemisia is virtually ubiquitous in the Northern hemisphere suggests that at a very early stage in human evolution women took its seeds with them wherever they went. Ironically, Artemisia’s very ubiquity is another contributing factor to what looks suspiciously like willful ignorance about it. For if modern science were to confirm the efficacy to which its traditional medicinal usage attests, then it would mean that those profiteering off of its more expensive and more risky alternatives would be out of business. Yet, if Artemisia is as efficacious as it seems to be, its ubiquity ultimately will render moot debates about whether, when or how women manage what are essentially symptoms of being a woman.

Because its ubiquity is evidence of the antiquity of Artemisia it is fair to assume it would have been known to Sappho. Although there is no reference to Artemisia in her poetry, a relatively long fragment focuses on Artemis (S. 44(A)(a)). It constitutes not only one of the earliest references to her but it is the only such reference in ancient literature that can be attributed to a woman and hence is uniquely authoritative.

After narrating how Artemis came to be called the “Virgin Deerhunter,” Sappho adds, “Eros never comes near her.” Though the fragment breaks off at that point, it seems to mean she thought of Artemis as having a force field around her. It is tempting to compare this to how one type of magnetic or electrical charge repels, rather than attracts, another of the same type. It appears, though, that Sappho had the force of a chemical reaction in mind, a reaction primarily detected by taste.

Sappho appeals to the sense of taste in characterizing Eros in another fragment as “bittersweet” (S. 130). While she refers to him with a word commonly translated ‘creature’ it could mean ‘insect’–a meaning consistent with how Eros was thought of in antiquity (most familiar today as Cupid of the Latin tradition). Because a flying insect such as a mosquito is directly experienced in being bitten by it, Sappho’s association of how Eros, as such an insect, ‘tastes’ to one bitten by him curiously combines myth and fact.

Given that context two facts become surprisingly relevant: Artemisia is an effective insect repellent and most types taste bitter. Therefore, Sappho had a factual basis for believing the plant Artemisia actually to be Artemis (she may have used the names interchangeably) because of the effect its bitterness had on Eros as an insect. Perhaps she tasted something of a homeopathic principle at work, with the ‘bitter’ of the bittersweet sting of the insect cancelled by the bitterness of the plant (cf. the magnetic or electrical charge analogy).

Precisely what type of Artemisia was known to Sappho and what type of insect she associated with Eros cannot be determined. Yet, not only is precision not necessarily applicable to the interpretation of poetry, but it is not, as a matter of scientific procedure, even logical (as Charles Peirce aptly noted). Especially where evidence is wanting, precision rather than generality or even vagueness risks cutting off in advance (praecidere) the relevant possibilities of what actually may prove to be true.

It is possible the ‘Eros’ insect for Sappho was the gadfly, oistros in Greek, the Latinized form of which was used to name the female hormone estrogen. That name was coined by ‘scientific’ men out drinking at a London pub in the 1930s (a “happy thought” as one of them put it). The only thing ‘happy’ about that thought–which implies a diagnosis of menstruation as a type of monthly malaria (and even madness)–is how it now can be related to S. 44(A)(a). For some attribute Artemisia’s effectiveness in certain cases to its ability selectively to target estrogen dependent chemical processes. Therefore, it would seem that what Sappho tasted as a mythological drama–a ‘Hunger Game’ between ‘bitter’ enemies–is in fact being played out on a molecular level when Artemis as Artemisia enters a woman’s bloodstream.

Stuart Dean has a B.A. (Tulane, 1976) and J.D. (Cornell, 1995) and is currently an independent researcher and writer living in New York City. He has studied, practiced and taught Tai Chi, Yoga and related disciplines for over forty years. Stuart has a blog on Sappho and the implications of her poetry for understanding the past, present and future: http://studysappho.blogspot.com/

Stuart Dean has a B.A. (Tulane, 1976) and J.D. (Cornell, 1995) and is currently an independent researcher and writer living in New York City. He has studied, practiced and taught Tai Chi, Yoga and related disciplines for over forty years. Stuart has a blog on Sappho and the implications of her poetry for understanding the past, present and future: http://studysappho.blogspot.com/

Thanks Stuart, your references to Sappho, in diverse contexts at FAR, are much appreciated. Just a citation here of the poem you mention and where Sappho delights in the bittersweet (Campbell/Loeb).

Once again,

limb-loosening Love [Eros]

makes me tremble,

the bitter-sweet,

irresistible creature.

LikeLike

Thanks Sarah.

LikeLike

Thanks, Stuart, for this informative and interesting post. I could easily relate to this sentence: “For if modern science were to confirm the efficacy to which its traditional medicinal usage attests, then it would mean that those profiteering off of its more expensive and more risky alternatives would be out of business.” For years, I’ve chewed on fennel seeds to relieve gastro-esophageal reflux–a remedy that works (at least for me) immediately–instead of swallowing Omeprazole, a pill prescribed by my gastroenterologist for the malady. Am exploring more and more the benefits of “alternative medicine.”

LikeLike

Thank you Esther. I first learned of Artemisia in part due to my interest in Tai Chi back in the 1970s. A Korean MD taught me how to treat my then girlfriend (now wife) with moxibustion. So I have about 40 years of anecdotes involving debates I have had over using nature first before using expensive Western approaches. FYI: several of the Artemisia’s are deemed especially useful for gastrointestinal issues.

LikeLike

Actually, the Nobel committee has been getting a tremendous amount of flack from the scientific community for awarding a ‘traditional’ medicine because of the links to alternative medicine.

Yes, alternative medicine is an anathema to the scientific community for the reasons you stated as well as the fact that most traditional medicines do not have to go through the rigorous rules and testing that modern, chemical derivatives must go through (the traditional herbs have been ‘grandfathered’ in) to comply with federal regulations. In the current field of alternative medicine, this can then lead to people making all kinds of claims about their herbal product, some of them true, others just plain quackery.

Nevertheless, for many chronic illnesses, Western pharmaceuticals can be ineffective and primarily treat symptoms. There will continue to be a robust market of desperate patients and their families for alternatives.

LikeLike

Very interesting! I learned about Artemis in junior high when I read Edith Hamilton, but Edith sure didn’t do the research you’re doing. (How could she??) I didn’t know about Artemisia until I took an herb class maybe 20 years ago. Thanks for doing the work and sharing what you know with us.

LikeLike

Thank you Barbara. Although I knew of Artemisia generally I did not realize its importance to women’s health until I did the research for my last post on Phaenarete, the mother of Socrates. I hope to write more on it–specifically related to Artemisia Vulgaris (Mugwort), which grows in abundance all over Manhattan. Here the research is fun and easy: I literally ‘sleep’ on it.

LikeLike

I loved this, Stuart, and learned a lot! Thank you for making a scientific subject such a pleasure to read (I am usually scared of the hard sciences!).

LikeLike

Thank you Vibha. If you are curious and/or have time, I have an entire section on ‘Sappho & Science’ on my blog on Sappho where I explain why I became interested in the scientific implications of her poetry and provide hyperlinks to similar posts.

LikeLike

I would very much enjoy that. Thank you for letting me know, Stuart!

LikeLike

Stuart, I gotta say, when I first saw your posts (from a guy!) showing up in FAR, it got my dander up. But you have consistently been so informative, so approachable, so downright knowledgeable that I now look forward to your writings. And this was another great one. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you very much. I appreciate your candor. From my first post over two years ago I have been mindful that my audience here would rightly have doubts about what I have to contribute–I keep meaning to write a ‘meta-post’–a post about why I am writing posts for a feminist forum. For now suffice it to say that my sympathies with many issues related to feminism began shortly after my second daughter was born when people began asking me “Aren’t you going to try for a boy?”

LikeLike

I presume we can know what form of artemesia grew on Lesbos in antiquity. That would probably be the same form that grows here today. In addition, we could check the works of Theophastos the biologist and botanist from Eressos (where Sappho may have been born). He lived a few hundred years after Sappho, but since many island plants are endemic, that should not be a major problem. Surprisingly a book I have on the plants of Lesbos esp those with medicinal properties does not mention artemesia.

LikeLike

I do not recall seeing Theophrastos mentioned in any of the literature I researched on this but I will keep an eye out for anything he might have said that could be relevant. In general, based on my harvesting Mugwort throughout my neighborhood in NYC (Washington Heights), I know that it can be very difficult to distinguish it from other Artemisias (Tarragon, for example) depending on the time of year you harvest it and what part of the plant you use (lower leaves vs. flower tops). It would not surprise me if there was more than one type growing in Lesbos depending on proximity to water sources and altitude. Though it might not explain the lack of reference to it in the book you have, there is little doubt in my mind that it often is passed over in silence because of the stigma of its use as a contraceptive/abortifacient.

LikeLike

A book on medicinal plants of Greece mentions artemesia absinthium (wormwood) as the common form growing in Greece.

LikeLike

Thanks Carol–that makes sense based on references to that type in ancient literature.

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you–I am humbled and grateful you took the time to read it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Mused by Magdalene and commented:

Once again,

limb-loosening Love [Eros]

makes me tremble,

the bitter-sweet,

irresistible creature.

I just referred in a poem of my own to the stories held in the names of plants and then I stumble upon this fascinating article. I’m very happy to pass it on.

LikeLike

Thank you very much!

LikeLike