As the Jewish High Holiday of Passover draws to a close, I have been reflecting on this seasonal ritual so central to collective Jewish identity and so significant to me personally.

The Haggadah, the script for the Seder gathering, enjoins all Jews to experience the Exodus—the liberation of the ancient Hebrews from slavery in Egypt —as if it were happening to each of us in our own time. Because I was born in Cairo to an Arab Jewish family that left Egypt when I was two, I always felt Passover to be mine. No need for “as if”: our Exodus was all too real. Yet, from my parents’ accounts, life in Egypt had been delightful. I could not reconcile the Haggadah’s dreadful representation of ancient Egypt with my family’s treasured memories of contemporary Cairo: I could not understand why we celebrated deliverance from an Egypt we loved.

Because the Hebrew word for Egypt, Mizraim, can mean “the narrow place,” I eventually understood the Exodus symbolically: as spring follows winter, Passover marks our emergence from cold constriction into warm freedom—but this image only works in the northern hemisphere.

A wider political vision makes the holiday more universally meaningful, and numerous nontraditional Haggadahs offer thoughtful guidance. I first used E.M. Broner’s Women’s Haggadah; later I relied on the Velveteen Rabbi’s Haggadah. Today I turn to Jews for Racial and Economic Justice’s Nobody’s Free Till Everybody’s Free; Tikkun’s Liberation Seder; T’ruah’s The Other Side of the Sea calling us to end contemporary slavery; and Rabbi Brant Rosen’s Expanding the Telling.

As Rabbi Rosen puts it,

the more we broaden our understanding of who ‘we’ are in this story, the more sacred will be our telling. . . . the Exodus story is not only about Israelites or Jews, but all who have cried out to God from the pain of persecution and oppression.. . . our telling of this story cannot be complete unless we include the experience of the Palestinian people, whose Exodus story is all too real and all too ongoing.

A writer who can help us towards a more expansive understanding of Passover is Egyptian-Jewish Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff who poignantly represents the rupture in her sense of self created by Passover.

Kahanoff belongs to my mother’s generation: I think of her as a literary foremother who helps me understand what it means to be Egyptian, Jewish, female, and feminist. Born in Cairo in 1917 to Iraqi and Tunisian parents, Kahanoff moved to the U.S. in 1940 and eventually settled in Israel, where she died of cancer in 1979. She was known for her essays (now available in a new collection, Mongrels or Marvels) advocating Levantinism as a multicultural, Middle Eastern alternative to European Israeli colonialism, orientalism, and racism. Throughout her career, Kahanoff returned again and again to the troubling violence against Egyptians inscribed in the Passover liturgy.

In her 1946 story, “Such is Rachel,” a young boy voices her distress: “It’s horrible,” he says about the Ten Plagues, “cruel”: “God couldn’t have done those things.” Similarly, in a 1959 autobiographical essay, Kahanoff recalls her childhood dream: “We and the Egyptians would be free together, and no one would set us against each other.”

In another essay, “Passover in Egypt,” Kahanoff describes her childhood friendship with a Muslim girl, Kadreya. Kadreya imagines “a religion where God is also a woman, not only a man”; she refuses to believe Kahanoff’s description of the Pharaohs’ oppression of the Israelites: “It’s not possible,” she protests. “I swear that not my father, or his father, or my grandfather’s grandfather would do such things to your father, his father, or his grandfather’s grandfather. I love you; you are my friend.”

Kahanoff assures Kadreya that “it’s all written in a book called the Haggadah.” Kadreya sobs, and Kahanoff is equally distraught. Yet when she attends her first Seder, her distress intensifies: “I couldn’t tell her about the Ten Plagues that had devastated Egypt.” Too ashamed to speak, Kahanoff withdraws from the friendship.

In her 1951 novel Jacob’s Ladder, Kahanoff has Ramadan, Easter, and Passover coincide: “in the streets, people lived in a common frenzy, by which Egypt welded their diversity into a unity.” Yet at home, her young heroine is shaken by the violence of Passover. She suffers with the Egyptian firstborn smitten by God and seeks an answer to her agonized question: “Is it wrong that I should love Egypt as my country?”

In her last published piece, “Welcome, Sadat” (1978), Kahanoff again highlights Passover, admitting that in her earlier representations she had not fully revealed the “anxiety, and even the terror” she felt as a child:

Most people summon up the “Exodus from Egypt” once a year; I bore it within me every day of the year, riddled with doubts concerning the Lord’s grace and love. Why should innocent fellahin have to pay such a heavy price for the Hebrews to be set free, while it was certainly in the Lord’s power to demand of Pharaoh to listen to Moses and let the Hebrews go. It seemed to me that the matter was not only cruel but a huge waste.

Kahanoff eventually came to an explicitly feminist resolution to her conflict, arguing in 1968 that “We need not be bound forever by the terms set by our ancient myths and holy scriptures. . . . we might interpret them within the context we now live in.” She suggests beginning with a new version of Ishmael and Isaac:

According to the patriarchal tradition only one son may be blessed; to supersede him the other son must either eliminate or dominate him. But a patriarchal society is not the one most of us would choose to live in today. . . . Hence, we might want to rewrite the story of Ishmael and Israel—and of their respective mothers—to give a happier opening onto the future.

Sarah and Hagar were rivals and victims within the framework of a patriarchal society; and while they are still among us, nothing prevents them from establishing a new covenant for themselves and their children.

This too is my Passover dream. Next year in Cairo and Jerusalem.

Joyce Zonana is the author of a memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, An Exile’s Journey. After participating in Carol Christ’s Goddess Pilgrimage to Crete in 1997, she served for a time as Co-Director of the Ariadne Institute for the Study of Myth and Ritual. Her essay “‘And she loved brown people’: Jacqueline Kahanoff’s Affirmation of Arab Jewish Identity in Jacob’s Ladder” appears in Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews in America, Vol. 13 of the Casden Review (2016), ed. Saba Soomekh, and is forthcoming in Sephardic Horizons.

Joyce Zonana is the author of a memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, An Exile’s Journey. After participating in Carol Christ’s Goddess Pilgrimage to Crete in 1997, she served for a time as Co-Director of the Ariadne Institute for the Study of Myth and Ritual. Her essay “‘And she loved brown people’: Jacqueline Kahanoff’s Affirmation of Arab Jewish Identity in Jacob’s Ladder” appears in Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews in America, Vol. 13 of the Casden Review (2016), ed. Saba Soomekh, and is forthcoming in Sephardic Horizons.

good post

LikeLike

I love the way you show us another way of being Jewish, Sephardic not Ashkenazi, Levantine not European, and feminist.

Kanoff says: “We need not be bound forever by the terms set by our ancient myths and holy scriptures. . . . we might interpret them within the context we now live in.”

I believe there is no other way to go for feminists (and others advocating peace and justice for all) in traditional religions. Judith and I discuss this in our forthcoming book. The question of course, is how far is too far. There is no clear answer to this question, as it will be decided in communities.

LikeLike

Thank you Carol. Yes, I completely agree: to make our traditional religions entirely inclusive, we must transform them. Off the top of my head, I want to say we cannot go too far . . . .

LikeLike

Wonderful summary. I, too, always felt that the Hebrew (male) God set the Egyptians up; if God had been female, would she have softened Pharaoh’s heart rather than harden it?

LikeLike

Yes. That’s the kind of miracle to celebrate! And it’s entirely possible.

LikeLike

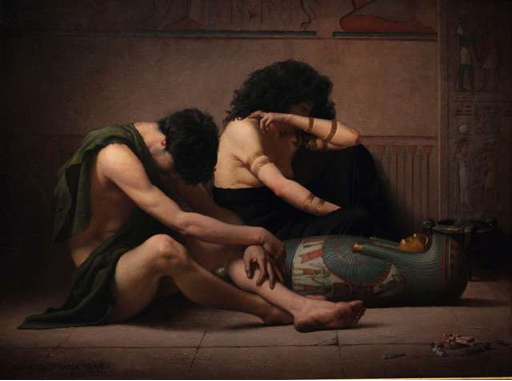

Love the Lynne Feldman painting, the matriarch at the head of the table. Found her online, interesting, very beautiful website.

LikeLike

Yes, her work is quite inspiring!

LikeLike

I love that painting also, Sarah. Off to a date with Ms Google am I!

LikeLike

I’ve been taking an e-course on World Religions through their Scriptures, (I’m only four (4) classes behind the others! 8-/). The classes on the Bible (Hebrew and Christian Scriptures) has led to more wondering about the story in Genesis 3 and how it’s been interpreted and how it effects our doctrine, ritual, etc. Someday, I will sit down and re-write the story.

LikeLike

And we will look forward to reading it!

LikeLike

Thank you, Joyce, for this essay. I especially like the inclusion of the following quote: “As Rabbi Rosen puts it, the more we broaden our understanding of who ‘we’ are in this story, the more sacred will be our telling. . ..” Looking forward to the day when this “broadening out” will be the norm in all religious traditions.

LikeLike

Thank you Esther. I was really struck by that quote as well. His Haggadah is wonderful.

LikeLike