Christmas morning. I don’t usually have Sundays free and our family holiday celebrations lean nontraditional, so I’d come to a special ecstatic dance celebration and brought my 9-year-old daughter with me. As the music started and people all around us began to flow and move, I reached out to touch her hand. As if she’d been doing it for years, she shifted into a beautiful contact improv flow with me, rolling her arm down and across mine as she beamed love and radiance right into my heart.

Christmas morning. I don’t usually have Sundays free and our family holiday celebrations lean nontraditional, so I’d come to a special ecstatic dance celebration and brought my 9-year-old daughter with me. As the music started and people all around us began to flow and move, I reached out to touch her hand. As if she’d been doing it for years, she shifted into a beautiful contact improv flow with me, rolling her arm down and across mine as she beamed love and radiance right into my heart.

This child brings up so many feelings in me as I watch her grow.

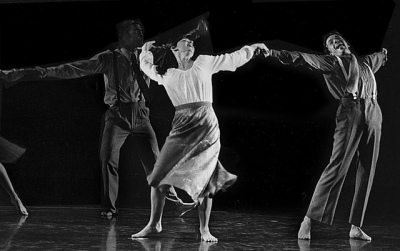

On many occasions at ecstatic dance, I’ve looked around the room and been overwhelmed by the beauty of the dancers and their joyful embodiment. When delight, peace, and ease are conditioned out of many of our bodily relationships through past traumas, body issues, or simply living in a disembodied or misembodied culture, feeling comfortable in our own skins is simultaneously an intentional act of cultural resistance and a profound act of self-care and self-love. Being present in the ecstatic dance space with lovely people moving confidently in fluid, sensual, emphatic, and silly ways fills my heart to overflowing on any given dance day.

Being present in that space with my daughter, looking around the room and imagining what it must look like through the eyes of a 9-year-old girl, gave it a whole new hue of meaning. People danced alone or with partners, men danced with men and women with women, all without shame over their bodies or feelings. The occasional dancer who slipped off to sit on the periphery, nursing tears that flow in the way holidays bring for some, was joined, held, hugged, cried with. My little girl danced with joyful abandon surrounded by men and women of all ages and shapes, present in their bodies and feelings, moving in ways that felt good, glowing with presence and the freedom of acceptance.

And yet the tears reveal that the ability to be fully present in our bodies and feelings is not always fostered in our families of origin and childhood communities. Those whose bodies fail to fit the normative center of standard acceptability, whether through appearance, size, or disability, may be too timid to claim the full freedom of embodiment in the face of cultural messages that equate diversity or limits with imperfection. Disability theologian Deborah Creamer, even as she points out that not all limits are advantageous, highlights the spiritual benefits of a model that accepts diversity of bodily limitations as normal and part of divine complexity: “The limits model demands that we reject unrealistic ideals or illusions of perfection, recognizing that such images lead to unproductive and dangerous dualisms.” Divine omnipresence, by nature of its all-containing expansiveness, necessarily contains diversity, limitations, and imperfection as part of its perfection. This is not a sign of our brokenness, but of our unity.

Theologian Nancy Cardoso Pereira has explored the ways in which the commodification of sexuality disconnects us from our bodies: “Alienation is not negation of the body, but an expropriation of sensuality and the erotic to the service of the appropriation of the product.” Capitalist co-optation of pleasure and bodies into markets of exchange reduces the body to its trade value, and the historical cramming of the untamed erotic into legalistic, medical, and psychological discourses reduces the body to its conformity and controllability – from an ars erotica to a scientia sexualis, from a “symbolics of blood” (and of flesh, skin, taste, and touch) to an “analytics of sexuality.” In exploring the ways we have translated the desire for sex into an “injunction to know it,” and how this knowing of sexuality has supplanted having of sex, reveling in desires, and embracing the pleasures of our bodies, Michel Foucault concludes that “the rallying point for the counterattack against the deployment of sexuality ought not be sex-desire [and thus more discourse], but bodies and pleasures.”

So what would it look like if from an early age, we grew up feeling safe in our bodies? What if our bodies weren’t shamed, violated, or abused, but were celebrated, honored, and loved, by us and by those who raised us, surrounded us, and taught us? What if as little kids, we all grew up regularly seeing adults – young and old, with and without disabilities, across the spectrums of gender and orientation, with all shapes and sizes of bodies – loving themselves, dancing freely, and caring for each other in vulnerability, with tender compassion, fully embodied and present with their feelings?

I know we can’t recreate the past – each of us is here shaped by the stories that brought us to our current awareness. But each of us is also here creating something new, for those who are now growing up and those who are yet to come. Pagan theologian Christine Hoff Kraemer posits that “when the right to pleasure is considered to be a basic human right, acts that do not nurture the body become clear ethical violations in a way that American society does not currently acknowledge.”

This has profound implications for social justice, but also for our personal practices of bodily presence and sexual expression. Would I have accepted years of my body serving the primary purpose of pleasure for others, a sex toy in tissue and disaster, without autonomy or direction or self-compassion, had I grown up with models for embodied joy and intentional, sensual presence? Would it have taken as long to come to a place where any lips that graze this tender flesh breathe blessing and respect across goose-bumped skin, and any touches, experienced only with consent, feed love, adoration, and shared pleasure deep into the parts of my soul that once laid abandoned or ignored, formerly littered with doubts and fears and self-loathing?

I want something better for my children. I want something better for all 9-year-olds – those we are raising, those we once were, and those whose lights will dot the future with sparkling hope and revolutionary fire. Will you help me create it?

I read this a week or so ago as FAR admin, and I find it so moving. I remember my parents going out to dances without us. So wonderful that you and your daughter could dance together! She is so lucky and so are you. So much dance in America is generation specific. Glad you found a way to break that pattern. And yes, to dance with abandon is to be in your body. So wonderful to learn that as a girl with your mom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that’s one of the things that I love most about our local ecstatic dance community — it is truly intergenerational. We have young folks in their twenties through people in their 60s and 70s, and many of us with families occasionally bring kids who are old enough to know how to honor the dance space. There’s even this adorable young couple who have brought their baby, wearing tiny ear-protecting headphones, and the baby gets passed around as mom and dad dance with friends. It’s a beautiful space to be in, surrounded by this group of people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Christy, Like you I had the wonderful experience of dancing with my 9-year-old daughter. We danced twice a week for 4 -5 years until she was 13 (and even then she occasionally came with me). We danced international folk dance, and for me those times were always the highpoints of my week. Ecstatic dance might have been even better.

LikeLike

Beautiful, Christy! Yes, I will help. I am!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting. I live mostly in my head and have never tried ecstatic dancing. Your daughter and your dancing friends are fortunate. Dance on!

LikeLike

I was a dancer as a kid (my mom was a dance teacher, so I grew up in a dance studio), but I spent a good bit of time in my head, and have appreciated getting back into my body through dance. I still spend a great deal of my time in my head. It’s interesting — through going to ecstatic dance, which is spontaneous, improvised, and freeform, I’ve realized how much of my prior dance was still “in my head.” Memorizing routines, thinking through specific steps, etc. I expected my initial ecstatic dance experiences to be perfect, but I spent a good bit of them continuing to dance through my anxieties over not knowing which ways to move my body. Now that is less so, especially in solo dancing, but I find myself still struggling with knowing what to do in partner dance situations.

LikeLike

It seems to me that the ability to dance equals freedom. If I tried to dance now I’d probably trip, fall, and break my hip! But reading your post Christy, in my mind and imagination my body is twirling and dipping and smiling.

Brings to mind the song, “Lord of the Dance”, and another called “Dance Dance Dance”, a little known song by Jim Manly sung in the United Church of Canada.

“Tall people are gorgeous, short ones are neat

Skinny or bulky each body’s a treat

So dance as you are, you were made by the One

Who calls you to be what you’ve only begun…and we’ll

Dance Dance Dance come dancing with me…

LikeLike

Barbara, If you’re enticed by the thought of dancing, I would encourage you to move to music in ways that feel safe and comfortable to you. Once you start, you gain strength and flexibility, and then tripping or falling is much less likely. Dancing doesn’t have to be athletic. It can just be expressive of what your body feels and wants to manifest at any given moment.

LikeLike

thanks Nancy. actually, I sometimes dance with my walker.

:-)

LikeLike

Nancy, that’s part of why I enjoy ecstatic — there aren’t any “moves” to learn, just moving your body in ways that feel safe and comfortable. Barbara, we do also have several dancers who come regularly who have various disabilities, including my husband, who is a stroke survivor and paralyzed on one side. Sometimes people come, rest on a mat against the wall, and bask in the vibes without dancing at all. It’s really just a lovely, safe, accepting space.

LikeLike

Growing up, I understood the body as something that was secondary (at best) to the soul. The soul, of course, is that immortal part of you. The body is mortal. (I’ve since learned that that separation (body/soul) is an arbitrary construct.) Emphasis was on building up the soul by attending to lots of rules and regulations. Dancing was verboten as it was “the vertical expression of the horizontal desire” and sex (a bodily kind of thing) was highly regulated. Sigh…., however, I don’t think my experience was unique. Thank you, Christy, for showing us a more integrated way of being.

LikeLike

Esther, that’s one thing that I want to explore if/when I do my doctoral work. I’ve noticed in the flow community (ecstatic dance, hoopdance, poi, etc.) that some have a very mind-action model in which the physical is subservient to the mind, and others have a very unified, neutral monism in which the body-soul separation is not a thing. I’m curious how they end up in each of those positions, and how they reconcile it with their movement practice.

I just came home from ecstatic dance, and tonight I was noticing that I dance in different ways with different partners (and I definitely do a lot of solo dancing when I’m there, as well). With some, it’s very sexy and hip-shaky, with some it’s very intimate and comforting, some are silly and fun, and others are very playful and theatrical. It’s nice to have that outlet for so many different kinds of expression!

LikeLike

I grew up, like Esther, “knowing” that the body was something that was secondary (at best) to the soul. I think maybe my dancing self was “saved” by Dick Clark and “American Bandstand.” My sister Barbara and I would stand in front of the TV and try to imitate the dance moves we saw there. Even if our parents thought rock’n’roll was “too sexy,” we just thought it was fun! And fortunately, they didn’t stop us from dancing.

LikeLike

Nancy, I’m glad they didn’t stop you from dancing! Movement can be so fun and playful!

LikeLike

By the way, the “book of the week” on the Greater Good website (which I recommend to FAR readers) is _How Pleasure Works_ by Paul Bloom.

LikeLike

Added that to my wish list. Thanks!

LikeLike

Your daughter is so lucky. I wish all parents could be like this. How healing. And you are right, we can still be parents to ourselves.

LikeLike

LaChelle, that is one of the most wonderful things I’ve discovered in my local dance community — how many of us are parenting ourselves, loving ourselves through discomfort, and reconnecting with our bodies, feelings, and autonomy in ways that we’d been denied in the past. It really is a healing practice for many of us.

LikeLike

That is so amazing. I am glad we can do the empowering work of choosing our own roles and labels, finding new ways to make meaning of them when it seems so real and what we need. Thank you again for this reminder to dance. Oh, how I could use it. :)

LikeLike