When I was 19, I fell hard into the kind of deep depression that hits college kids whose unstable upbringings, rife with inconsistency and trauma, left them ill-prepared to face the self-direction and responsibility of independence. I didn’t grow up religious despite my father’s attempts to turn visitation weeks into conversions, but had started attending the local Episcopal cathedral months earlier after seeing its stunningly beautiful windows on a historic tour. Having taken basic stained glass courses when I was 18, I’d been mesmerized by the artistry and would sit in a different pew each week, drifting into and out of awareness of the service, eyes trained on the nearest window, lost in contemplation, love pouring in.

When I was 19, I fell hard into the kind of deep depression that hits college kids whose unstable upbringings, rife with inconsistency and trauma, left them ill-prepared to face the self-direction and responsibility of independence. I didn’t grow up religious despite my father’s attempts to turn visitation weeks into conversions, but had started attending the local Episcopal cathedral months earlier after seeing its stunningly beautiful windows on a historic tour. Having taken basic stained glass courses when I was 18, I’d been mesmerized by the artistry and would sit in a different pew each week, drifting into and out of awareness of the service, eyes trained on the nearest window, lost in contemplation, love pouring in.

When the darkness became too much and I sought more of that love through spiritual care and reflection, I walked into the church library and thumbed through the directory looking for resources, and was hopeful to discover that the Episcopal Church had convents. That afternoon, I dialed the number for the nearest convent, and in that especially dramatic way of depressed 19-year-old artist types with backgrounds in theater, I declared that I couldn’t handle life in the world anymore and that I might want to become a nun. Sister Ann told me that their order was less an escape from the world than a new way of being fully present in it, but invited me to spend Christmas at the convent.

What started out as a holiday visit became several months of me spending every day that I wasn’t in class or at work at the convent, living in the guest house, attending five services a day, helping with maintaining the grounds, and spending as many waking hours as I could in the library, face buried in the works of medieval women mystics. Over the coming years, I’d spend many long weekends in retreat at the convent, and the sisters became my second family. I visited with women I was dating and later with a Muslim boyfriend, and everyone was always welcomed with love. When my first child almost died as a newborn and I called to ask for prayer, two sisters drove to be with me in the hospital. I still cry now, twenty years later, when I tell people the story of a parish priest leading the small group gathered in my hospital room in prayer after my son’s first surgery, and how my heart swelled when halfway through the Lord’s Prayer, teary eyes closed, I began to hear the familiar lilt of women’s chanting over our soft-speaking voices.

Before moving to start a new life as a single mom a few states away with my infant son, I visited the convent. One of the sisters to whom I had become especially close was nearing the date when she’d take her final vow – that of poverty. She gave me a small, delicately-wrapped gift box, and when I opened it, inside were earrings and a bracelet, both of jade. The accompanying card said, “For Christy, who is a shining example of Christian love.” The words sounded like they were meant for someone else, and I had a hard time wrapping my mind around how anyone could see me that way. I felt like a bad Christian – a weird and broken queer kid whose life story read more like a How to Sin Like You Mean It manual than an Example of Christian Love. All of my experiences with Christians before the convent, particularly living in the American South, had been experiences of judgment, exclusion, and shame. Whatever brief moments of “fitting in” I’d experienced among Christians had been achieved at the cost of authenticity, earned by denying and repressing parts of myself and my belief and my story that would have otherwise brought down shame and judgment.

Before moving to start a new life as a single mom a few states away with my infant son, I visited the convent. One of the sisters to whom I had become especially close was nearing the date when she’d take her final vow – that of poverty. She gave me a small, delicately-wrapped gift box, and when I opened it, inside were earrings and a bracelet, both of jade. The accompanying card said, “For Christy, who is a shining example of Christian love.” The words sounded like they were meant for someone else, and I had a hard time wrapping my mind around how anyone could see me that way. I felt like a bad Christian – a weird and broken queer kid whose life story read more like a How to Sin Like You Mean It manual than an Example of Christian Love. All of my experiences with Christians before the convent, particularly living in the American South, had been experiences of judgment, exclusion, and shame. Whatever brief moments of “fitting in” I’d experienced among Christians had been achieved at the cost of authenticity, earned by denying and repressing parts of myself and my belief and my story that would have otherwise brought down shame and judgment.

In his essay “The Body’s Grace,” Rowan Williams puts forth that the rationale of the Christian community is “to so order our relations that human beings may see themselves as desired, as the occasion of joy.” While Williams focuses his essay on ways in which sexual intimacy transforms us spiritually by allowing us to see ourselves as God sees us – as an occasion of joy – I was struck as I reflected on his work by the fact that the first time I remember seeing myself as an occasion of joy for another was not in the presence of a lover, a parent, or a preacher, but in the love of a religious sister with whom I’d poured out all my shortcomings and failures in letters and tears and plainsong. To have my deepest flaws witnessed in love and accepted without reservation or judgment introduced me to the experience of grace – the experience of being loved as God loves me, as God loves God. Years of experiencing judgment through the words and actions of Christians I had known did little to draw me into the presence of God; if anything, they drove me away from the label “Christian.” What Sister Ann offered was not judgment but acceptance, not punishment but healing, not separation but the unifying reflection of divine grace that binds us to each other and to God in the shared experience of unearned blessing and radical love.

In the two decades since receiving this gift of grace, I’ve come to see my path as more interfaith than specifically Christian, yet I still draw inspiration and guidance from medieval mystics as well as modern Christian thinkers like Matthew Fox, Thomas Berry, and Sallie McFague. But this grace that is found in seeing ourselves as occasions of joy for others, for ourselves, and for God? It is the standard against which I compare every Christian evangelist, every politician who claims moral authority, and every executive order or law passed in the name of religious freedom and spiritual protection. If our actions and words do not welcome the uprooted refugees seeking safety for their children and freedom from violence or protect the vulnerable in their access to basic necessities of living and healthcare, then they are not words of compassion or grace. If our laws do not allow queer and trans people to move freely through their communities without harassment and exclusion, our laws are not laws of freedom. If divine love is not extended through our actions and activism to people of color as fully as white people, to women as fully as men, or to protections of tribal people and lands more fully than corporate, then any claim to love we harbor is limited by its exclusivity, distorting and hoarding grace as if it were a limited resource. If we are called to show others, through their interactions with us, that they are occasions of joy, then we are failing, America. We can and must do better.

bueatiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

I admire your persistence, I admire the women at the convent, and I agree with your conclusion. People who claim to be people of faith–no matter what their religion is–are often self-deceived, but those nuns sound like the real deal. I’m glad you found them. But we do have to do better than we’re doing at present.

LikeLike

I’m glad I found them, too, Barbara. I’m often impressed that the monastics I’ve known (most of whom have been in Episcopalian orders) have been some of the most devoted, open-minded, fully compassionate people I’ve known. One of my old college friends is a brother in the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, and I had tea with him at the monastery while visiting Cambridge last fall. We talked at length about where we each are in our current spiritual lives, and the warmth and acceptance were tangible. Once you’ve experienced that kind of Christian love, the expectation and possibility are set high for others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved this post, Christy. It mirrored my own experience with most Sisters throughout my life. Wish I had lived so lovingly and with open heart. But I keep trying and growing.

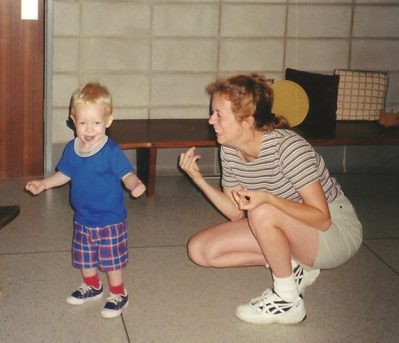

Loved the picture of your boy too! I pray his health is strong, his heart is happy, and his feet continue to dance. Yours too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Barbara! He is now 6’2″, a college junior, parkour enthusiast, and fire spinner, so he’s definitely strong, healthy, compassionate, and bright!

LikeLiked by 1 person

:-)

LikeLike

A beautiful post, Christy. Thanks. I believe that love is at the core of all religions. That’s where they come together. So as a loving pagan, I’m making telephone calls, writing letters to the editor, boycotting Trump’s goods and services, and hoping in these ways to open up a little more acceptance, if not love, for people under threat from the Trump administration.

LikeLike

The love at the core of all religions is what fuels my interest in religion, as well as my frustration with religious-based discrimination and othering. Hopefully as each of us speak out and act in ways that are in accordance with our understanding of that love, change will happen.

LikeLike

I also have known grace among the sisters, Episcopal and Roman Catholic. Thank you for this beautiful post. It brought back memories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Moving and beautifully written essay – being witnessed by others who see us for who we are and being accepted is probably the most powerful aspect of Love that I have even experienced…

LikeLiked by 1 person