As so many of us recoil in horror at the Trump administration’s cruel attempts to enforce an impenetrable border between the U.S. and Mexico, I find myself struggling to understand what he and his supporters mean by “borders,” and why they are so invested in maintaining them. The administration’s vicious immigration policy, recently epitomized in a brief tweet on June 19th, 2018—Juneteenth, the day in 1865 when slaves were finally freed throughout the U.S. at the end of the Civil War—“If you don’t have Borders, you don’t have a Country” has sent me back to Gloria Anzaldúa’s visionary 1987 book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza.

As so many of us recoil in horror at the Trump administration’s cruel attempts to enforce an impenetrable border between the U.S. and Mexico, I find myself struggling to understand what he and his supporters mean by “borders,” and why they are so invested in maintaining them. The administration’s vicious immigration policy, recently epitomized in a brief tweet on June 19th, 2018—Juneteenth, the day in 1865 when slaves were finally freed throughout the U.S. at the end of the Civil War—“If you don’t have Borders, you don’t have a Country” has sent me back to Gloria Anzaldúa’s visionary 1987 book, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza.

Grounded in her experience as a queer mestiza raised in the Texas/Mexico borderlands, Anzaldúa’s bilingual, cross-genre manifesto argues for the transformative role of the mestiza, no longer “sacrificial goat” but “officiating priestess at the crossroads”:

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning of a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war.

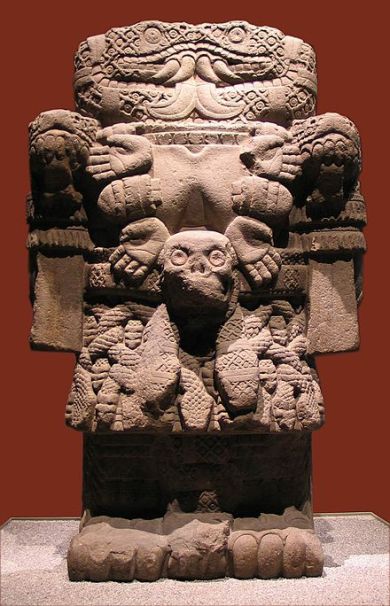

A central image Anzaldúa uses to help uproot the toxic dualism she diagnoses so compellingly is Coatlicue, the ancient Aztec earth goddess who symbolizes “the fusion of opposites,” incorporating “heaven and the underworld, life and death, mobility and immobility, beauty and horror,” and, most importantly, “the eagle and the serpent,” animals that, “like the ocean,” do not “respect borders.”

It is dualistic thinking that creates borders, dualistic thinking that is at the root of the Trump agenda, dualistic thinking that we must work to undo, in ourselves as well as in others. But how?

We must begin, I suppose, by acknowledging the easy comfort we all find in boundaries, of drawing within the lines. “Borders,” Anzaldúa tells us, “are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge.” Borderlands, on the contrary, are “vague and undetermined” places “created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary”:

The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants. Los atravesados live here: the squint-eyed, the perverse, the queer, the troublesome, the mongrel, the mulato, the half-breed, the half dead; in short, those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the “normal.”

Living in the borderlands—whether those between “nations,” “races,” “genders,” “religions,” or “sexualities,” can be uncomfortable, though, as Anzaldúa argues and demonstrates, with respect to gender here, but equally true for nation and race and all the other dualisms:

There is something compelling about being both male and female, about having an entry into both worlds. Contrary to some psychiatric tenets, half and halfs are not suffering from a confusion of sexual identity, or even from a confusion of gender. What we are suffering from is an absolute despot duality that says we are able to be only one or the other. It claims that human nature is limited and cannot evolve into something better. But I, like other queer people, am two in one body, both male and female. I am the embodiment of the hieros gamos: the coming together of opposite qualities within.

Several years ago, I faced within myself the intimate challenge of life in the borderlands. A man I had just started dating, and to whom I was deeply drawn, suddenly announced that he had decided to begin taking hormones, that—at the age of 65, after a lifetime of gender dysphoria—he was ready to transition. Would I join him on the journey? He expected that I would, for, after all, I had spent more than twenty years living as a lesbian, loving women. Surely I would continue to love him as he became the woman he had always felt himself to be.

But I found that I could not, that the categories of “male” and “female” were more rigidly fixed in me than I had realized. For several months I struggled to accept my lover’s transition, still only in the planning stage at that point, trying as hard as I could to visualize a transformation from “he” into “she,” or even “they.” Despite my own bisexuality and theoretical embrace of gender fluidity, I could not, in my body or even in my use of language, come to terms with this challenge to my perception (I had thought him such a “masculine” man!) and sense of self. Ashamed, I abandoned my new friend.

I should have done better. As, of course, should the U.S. and all the other nations and individuals that are currently seeking to enforce national and gender and sexuality and religious and racial boundaries.

But, as Anzaldúa reminds us, we must first honor and acknowledge the challenges we face when we begin to enter the borderlands. And we must have compassion for those who are still too frightened to venture beyond their “safe” spaces. It’s our job, as “priestesses of the crossroads,” to usher them in.

The struggle is inner: Chicano, Indio, American Indian, mojado, mexicano, immigrant Latino, Anglo in power, working class Anglo, Black, Asian—our psyches resemble the bordertowns and are populated by the same people. The struggle has always been inner, and is played out in the outer terrains. Awareness of our situation must come before inner changes, which in turn come before changes in society. Nothing happens in the “real” world unless it first happens in the images in our heads.

In order to transform what is happening at the Mexico/U.S. “border” (and elsewhere) we must first break down the borders within our heads—all the borders in all our heads. Mr. Trump tells us “If you don’t have Borders, you don’t have a Country”; my response today is: “Who needs countries? Who needs genders? Who needs races or competing religions? What we need is Coatlicue.”

Joyce Zonana is the author of a memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey. She served for a time as co-Director of the Ariadne Institute for the Study of Myth and Ritual. Her translations from the French of Henri Bosco’s Malicroix and Tobie Nathan’s Ce pays qui te ressemble are forthcoming from New York Review Books and Seagull Books.

Thank you for sharing your thought-provoking insight. I guess that the message is exactly was mos appropriate for me to hear today, my 50th birthday!

LikeLike

Happy Birthday! Thank you for reading and responding.

LikeLike

When I was in graduate school for psychology, we learned that analyzing variables as continuous, evolving concepts, rather than as categories, is usually the more statistically robust method. I think that sitting with the ambiguities possible in gender, race, religion and other demographic variables can be discomforting, but, as you’ve so aptly described, believing there to be clear boundary lines where there are in fact borderlands can cause much destruction and suffering.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your comment, Suzanne. I love the notion of “variables as continuous, evolving concepts.” It’s certainly truer to lived experience, no?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant post! I remember visiting the West Coast and meeting a man from Central America who explained how artificial and harmful the United States border is. People and animals have been moving up and down that terrain for millennia. Nation states are an artificial and relatively recent human construct that is already becoming obsolete.

I am also reflecting on boundaries, as in personal boundaries and how that relates to borders. Having worked with survivors of sexual abuse and other forms of violence, I know that being able to assert and protect physical and emotional boundaries is essential.

I wonder how this personal need relates to political and geographical boundaries.No conclusions, just pondering. Thanks again for this thought-provoking post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s an important point, Elizabeth . . . yes, I agree that we need emotional/physical boundaries for safety and health; perhaps our vulnerabilities in those respects might lead to our intransigence about the political/geographical . . . don’t know. But, as you say, “nation states are an artificial and relatively recent human construct.” Migration has always been a part of human life on this planet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As a trauma survivor and advocate for survivors myself, I had the same pause when I considered personal boundaries. I agree it deserves careful consideration, but, at first glance, what comes to my mind is the idea that survivors often have to work to establish boundaries where before none were recognized, but may, at a later stage, also spend time building flexibility and nuance into what previously was rigid out of necessity. The more I contemplate these ideas, the more I am drawn to the ideas of developmental and cognitive psychologists. We first learn as children to put things into categories (think of the child who mislabels animals, for instance) but then, as we go into adolescence, we (sometimes!) are able to envision the world as consisting of both stark and subtle differences, with concepts overlapping and spilling into each other. I would argue that, in relinquishing certainty and “the Truth” and by conceptualizing our personal boundaries as natural structures, subject to the forces of nature and ever-changing, we gain the ability to hold our own space as sacred as well as to invite others into that space when we so desire. We can also then, potentially, meet others as full-fledged Mystery, layer upon layer to be revealed, rather than as a series of labeled, known entities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I wrote this, Suzanne, I was thinking too about my own “boundary issues” when I was younger (and still today, at times) . . . I had a very poorly developed sense of self and was rarely able to protect myself against all sorts of incursions, emotional and physical . . . so I needed to develop rigid boundaries . . . which I have lately been learning to relax in order to experience and encounter, as you say so beautifully, “full-fledged Mystery.” Thank you for your thoughtful comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said, Suzanne. As we become more secure in our ability/right to choose, to say “yes” or “no,” or “I need time to think about it. I’ll get back to you,” we can be more flexible and nuanced in our responses to others. How might that confidence and flexibility be reflected in relations between nations?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“the idea that survivors often have to work to establish boundaries where before none were recognized,”… I know that was true for me – flexibility came afterwards – it’s a process. Great point!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds like we are making a distinction between “borders” and “boundaries”, which has meaning for me, also with a history of abuse. But when I moved into these apartments a few years ago, there was a woman (now deceased) who was no respecter of boundaries. She would get “into people’s faces and space” and pry into personal issues. It felt like an assault. She used to be the head nurse on a hospital ward and probably saw nothing adverse in her behaviour. But I used to put something between us, like my walker. I wonder if that is the feeling and image that Trump is arousing in people; the sense that personal space is being invaded. And I wonder if he himself carries a feeling of being “invaded”. He is a very damaged person who proves that money can’t buy happiness or wholeness. And he is a person very dangerous to the welfare of the world in his present position.

LikeLike

Great comment, Barbara. Yes, I think Trump is indeed arousing people’s fear of invasion of their personal space and it may well be that he himself has those very same fears. Or else he’s entirely cynical and manipulative. Hard to say. In either case, he’s very very dangerous to us all. And, yes, boundaries and borders may not be the same thing at all!

LikeLike

I don’t think the Ogre-in-Chief has any inner being. All he has is narcissism, which requires borders so he can be better than anyone else. Yes, he is highly dangerous to the planet and every being that lives on it.

Thanks for writing this interesting, lucid study of personal borders and boundaries and your own history. Good luck to your friend. And you, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Barbara!

LikeLike

“What we need is Coatlicue.” This image says it all.

I loved the honesty in the telling of your personal story. If only more of us would share them. We are all struggling with this inner split. It is perhaps the greatest disease of all time.

Thank you so much.

By the way, Anzaldúa’s work helped me change the way I saw the world – and it gave me a place to “be.”

LikeLike

Thanks so much Sara. The image is, of course, Anzaldúa’s: she showed the way!

LikeLike