The liturgy of Yom Kippur states: “On Rosh haShanah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed: who will live and who will die, who by fire and who by water…” This prayer refers to a legend mentioned in the Talmud, in which the righteous are written in the book of life while the wicked are written in the book of death (and those of us who fall in-between get our own book of “in between” people.). During the High Holiday season Jews pray again and again to be written in the book of life, but by the end of Yom Kippur the language has changed: we pray to be “sealed” in the book of life. But what is this “sealing”?

The liturgy of Yom Kippur states: “On Rosh haShanah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed: who will live and who will die, who by fire and who by water…” This prayer refers to a legend mentioned in the Talmud, in which the righteous are written in the book of life while the wicked are written in the book of death (and those of us who fall in-between get our own book of “in between” people.). During the High Holiday season Jews pray again and again to be written in the book of life, but by the end of Yom Kippur the language has changed: we pray to be “sealed” in the book of life. But what is this “sealing”?

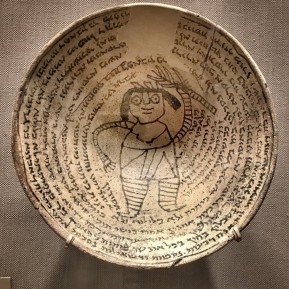

This season, as part of my sabbatical writing project, I have been studying the magical practices of Mesopotamia in the 6th-8th centuries. One fascinating example of these practices is the making of “incantation bowls.” This ritual, done by Jews as well as Christians and Mandaeans, involves inscribing a ceramic bowl with a spell of protection or healing, and then burying it under a threshold or in the corner of a home. The words frequently are written in a spiral or other pattern, and sometimes include an image of a chained demon at the bottom of the bowl. Typically the spells invoke divine and angelic names against demonic forces. Sometimes the bowls even speak of “divorce”—particularly, divorcing the demon Lilith and sending her away. Most typically, the bowls use the language of “sealing”—i.e. sealing demons out of a home.

The bowls, excavated from Mesopotamia, are from the same period as much of the Babylonian Talmud. In fact, the two major witnesses we have to this place and period in Jewish history are the Talmud, and the incantation bowls. The incantation bowls, as well as some talmudic texts, show us that Jews, like others at that time, were concerned about subtle malevolent forces that might harm them.

Here is one typical example of the text of such a bowl:

Sealed and countersealed are the house, dwelling, possessions, sons, daughters, cattle, and soul of Ahai son of Ispandarmid and Ispandarmid daughter of Qiomta his wife, and all the members of their household. They are sealed and countersealed from a demon, from a persecutor, from a male and female idol, from a Lilith… and from anything evil. They are sealed and countersealed by the name YH YHWH Tzevaot. Amen amen selah, haleluyah haleluyah.[1]

Here’s another one, made for Ahat daughter of Imma and her children and extended family:

Sealed and countersealed and fortified are Ahat, the daughter of Imma; Rabbi, Malki and Dipshi, the sons of Ahat; and Yanai the daughter of Ahat, and Ahat the daughter of Imma, and Atyona the son of Qarqoi, and Qarquoi the daughter of Shilta, and Shilta the daughter of Immi—they and their houses and their children and their property are sealed with the seal-ring of El Shaddai, blessed be He, and with the seal ring of King Solomon, the son of David, who worked spells on male demons and female liliths…[2]

Here’s part of another one, which I love because of its language about the bond of heaven and the seal of earth:

They [the demons] are bound and sealed, bound by the bond of heaven and sealed by the seal of earth (isirin b’isra d’shemaya vechatimin bechatma d’ara), bound by the seven bonds that are not loosened and sealed by the seven seals that are not broken… sealed by the great seal (chatma raba) that is not loosened.[3]

The “great seal” mentioned in this bowl may refer to the seal which God used to seal the universe so that chaos would not enter. There are a number of Jewish sources that deal with God’s sealing of the world to protect it from primordial chaos, including the Babylonian Talmud (Sukkah 53b) and Sefer Yetzirah (a mystical text of the 6th-7th century). In these tales, it is the Divine name itself that God inscribes in order to seal the boundaries of the earth.

It is notable that the incantation bowls are always written for an individual who is named (i.e. they’re not made generically but for a specific person). It’s also notable that they are frequently made for, and maybe by, women. Typically, women had more access to material ritual (i.e. magical objects and practices) than they did to sacred text—though these bowls are in fact both artifacts and texts. A number of feminist authors, among them Maggie Anton and Dorit Keidar, have suggested that these bowls were written primarily or entirely by women.[4] Maggie Anton has written a series of novels on the subject (the Rav Hisda’s Daughter series). If this speculation has truth to it, then the God who seals the world using divine names is acting in a manner parallel to a sorceress.

At the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute several years ago, we had Maggie Anton come and teach for the weekend, and then the group made incantation bowls: for healing, for protection, for fertility, for anti-racist social justice, and more. It was powerful to watch people work on these bowls, bringing to life this ancient practice that Jews once used to express their fears and hopes. We discussed what to do with them: display them, break them, bury them as was the ancient custom. As I watched my own community work with this practice, I understood these vessels to be a way that my ancestors set their intentions, exercised their creativity, and claimed their spiritual power. While I know it wasn’t always possible to keep away illness, violence, and sorrow, no matter what rituals one performed, I see in these bowls a desire to protect one’s loved ones in a dangerous world, a desire that I relate to very deeply in this uncertain time.

So as Yom Kippur ends and I recite the ancient formula of “seal us in the book of life,” I will be thinking of my ancestors who made bowls and inscribed them with spells and divine names, and sealed their houses from what frightened them. I will be imagining that, as Maggie Anton speculates, there were women practitioners from whom one could commission such a bowl, and thinking of the comfort and witness those women might have offered the ones who came to them for help. And, I will be setting my own intentions: creating around myself, my family, my community and my world, a ”bowl” full of fierce love.

References:

Duling, D.C. “Testament of Solomon: 1st to 3rd Centuries A.D.” in Old Testament Pseudepigrepha, Vol. 1, ed. James H. Charlesworth (Hendrickson Publishers, 1983), p. 948.

Hunter, Erica C.D. “Incantation Bowls: A Mesopotamian Phenomenon?” in Orientalia, vol. 65, no. 3 (1996), p. 220-233.

Levene, Dan. “Curse or Blessing: What’s in the Magic Bowl?” Presented during the Ian Karten Lecture, University of Southampton, 2002. Published in Parkes Institute Pamphlet, 2002.

Shani, Ayelett, “Bewitched: What makes a Jewish Sorceress?” HaAretz, Dec. 6, 2013. https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-what-makes-a-jewish-sorceress-1.5297200 Accessed Sept. 18, 2019.

[1] Levene, Dan. “Curse or Blessing: What’s in the Magic Bowl?” Presented during the Ian Karten Lecture, University of Southampton, 2002. Published in Parkes Institute Pamphlet, 2002.

[2] Duling, D.C. “Testament of Solomon: 1st to 3rd Centuries A.D.” in Old Testament Pseudepigrepha, Vol. 1, ed. James H. Charlesworth (Hendrickson Publishers, 1983), p. 948.

[3] Hunter, Erica C.D. “Incantation Bowls: A Mesopotamian Phenomenon?” in Orientalia, vol. 65, no. 3 (1996), p. 220-233.

[4] Shani, Ayelett, “Bewitched: What makes a Jewish Sorceress?” HaAretz, Dec. 6, 2013. https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-what-makes-a-jewish-sorceress-1.5297200 Accessed Sept. 18, 2019.

Hi Jill, Thank you for this interesting and informative article on incantation bowls. I’ve never heard this concept of sealing before and I wonder if you would not mind explaining it more. Kind regards, Karen

LikeLike

Thanks, Karen. “Sealing” in the context of the bowls means erecting a spiritual/metaphysical barrier to negative or chaotic forces. It’s often done in magical ritual. Being “sealed” in the book of life is similar but a little different– more like sealing a letter closed so no one can open it.

LikeLike

Thanks Jill, the bowls so beautiful. Love especially the uniqueness of the geometric forms in the last one.

LikeLike

Me too! Thank you, Fran.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jill. I have wonderful memories of that session.

LikeLike

I am so glad!

LikeLike

Very interesting! I think it’s especially significant that the women made these bowls. We need bowls today to seal out the demons called Trump and his friends. Women need bowls with seals of protection so that they will not be sexually or otherwise abused and will be believed. The past week has especially shown us this need. Blessings to you and your students/friends and their bowls.

LikeLike

Yes, we could use a whole shipment of incantation bowls right now…

LikeLike

Sitting here thinking of my pottery bowl, and what I would paint around it. How do I visualize the Holy One and Love at the centre, what are the things within me that hinder and even oppose Good – things in me that I want to change. And the dangers outside, the world-wide resurgence of the extreme right ideology, worship of profit, violence, all those things that scare me and grieve me as I see them in action.

What a fascinating way to meditate, and illustrate, what we experience in our lives. Thank you Jill

LikeLike

I appreciate your reflection so much, Barbara. I hope you make one.

LikeLike

Illuminating essay – I never heard of incantation bowls – a wonderful idea… and surely they were all created by women – prayers and bowls just seem to go together. Just now I would like to imagine that every woman who endured a rape and is re-experiencing that trauma could have one of these bowls buried for her.

LikeLike

What a powerful ritual that would be. Thanks, Sara.

LikeLike

i never heard about bowl which mentioned

shortly every one would like to know more and details about it

thanks “jill hammer”

LikeLike

that is incredible

if the bowls which mentioned as “great seal” to seal the universe only to chaos can’t enter to the world

why the chaos is still have??

LikeLike

Very interesting practice. I’m not particularly supernaturalist, but I can see how these can be adapted to different interpretations of sealing.

LikeLike

If ordinary women made the bowls, perhaps they made them with snake coils, another reason snakes were once viewed as sacred.

LikeLike

Living in Greece I have found that most women use the churches to light candles and pray for their families, for health, healing, getting into college, getting married, etc. This can be dismissed as popular or low religion, it is popular insofar as many people do it, but I no longer view it as “less than” thinking theologically.

LikeLike

Hi Jill

I just acquired one of these bowls with the same image in the first picture. Are you able to translate them? Is there a way I might be able to email images of the bowl I have? The one I also have looks like a lid than a Marisha (Drinking bowl)

LikeLike