When I was growing up, home was the last place I wanted to be. It’s not that ours was an abusive or angry household: both parents loved me and my mother labored to create a calm, clean space to contain us all. It’s just that I felt suffocated.

When I was growing up, home was the last place I wanted to be. It’s not that ours was an abusive or angry household: both parents loved me and my mother labored to create a calm, clean space to contain us all. It’s just that I felt suffocated.

Part of the problem was that we were immigrants. My parents were struggling to find their way in an alien culture, and, with little else to hold onto, they clung to their customs and traditions. I wanted to be “American,” to mingle with classmates, to venture into the vastness (New York City!) just beyond our door. The Middle Eastern culture from which we hailed had strict rules for women and girls, and my mother expected me to follow them. She herself was an excellent cook, a creative seamstress and scrupulous housekeeper, a devoted and dutiful wife. I rejected all of it, refusing to cook, ripping out seams, balking at my weekly chores of dusting and vacuuming and ironing. Instead I dreamt of life as a writer, a renegade, an outlaw. My role models were hobos and witches and gypsies; more than anything, I yearned to be free, longing to “walk at all risks,” like Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh.

It’s true too that our home was always cramped. At first, my parents and I lived in one rented room. Later, we were five in a tiny, two-bedroom, one-bath apartment. I shared a room, first with my infant brother and then with my elderly grandmother. When he grew older, my brother slept in the living room . . . None of us had any privacy, and so rooms of our own became cherished dreams. I moved out when I was eighteen, and I have been moving, again and again, ever since.

This year of being mostly homebound, confined to the company of my husband and our two kittens, has been–for me, as for so many others–a challenge. And also an adventure. Just this past week, when eighteen inches of snow blanketed the hills that surround our upstate New York house, I did not set foot outside for a full seven days, spending my time cooking, cleaning, and knitting–yes, knitting! My grandmother had been a knitter. And for the longest time I’d wanted nothing to do with my grandmother.

These days, to my surprise, I’m learning to value the women’s work my mother and grandmother tried to teach me, finding pleasure in the slow rhythms and rich textures of needlework; the simple, repetitive steps of preparing daily meals.

And this house where we find ourselves: it’s a twelve-hundred square foot, two- hundred-year-old farmhouse deep in the countryside, a slightly ramshackle, tumbledown affair. But it’s a house with a deep history, a history that binds me in its spell.

When my brother acquired the house as a ski getaway in 2003, he befriended the neighbors, Elnora Mulford and her son Gordon, each of whom lived in modern homes on either side of this one. Elnora had moved to this farmhouse as a young bride in the 1930s. Gordon was born in the bedroom where we now sleep; he lived here until his own marriage in the 1960s.

When my brother acquired the house as a ski getaway in 2003, he befriended the neighbors, Elnora Mulford and her son Gordon, each of whom lived in modern homes on either side of this one. Elnora had moved to this farmhouse as a young bride in the 1930s. Gordon was born in the bedroom where we now sleep; he lived here until his own marriage in the 1960s.

I first started spending time in the house in 2005, after being displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Slowly, as my brother used the house less and less, I came to use it more and more . . . until four years ago, when my brother turned it over to me and my new husband Mike.

But until this year, I hadn’t actually lived here.

It wasn’t a deliberate, conscious choice. Just before the lockdowns began, I was at a writing retreat in New Hampshire. Mike had planned to spend a month alone here—a retreat of his own. On March 14th I returned in a panic; a few days later I insisted on adopting two new kittens (my beloved cat Ginger having died a few months earlier) . . . and so, while the pandemic raged in New York City, we burrowed into this country home, little dreaming that the days would become weeks would become months. Although we visited the city occasionally, the cats kept us bound. They were having enough trouble adjusting and we didn’t want to traumatize them by displacing them again. Perhaps it was ourselves we didn’t want to traumatize.

As the days continue to stream past, I discover that this house is the perfect container for my dreaming self. Unlike any other place I’ve lived, it has an upstairs and a downstairs, although the upstairs is no more than a finished attic. There’s even a very unfinished basement, visibly dug from the rocky earth. There are windows (many of them old and cracked) on all four sides. And, best of all, there are layers and layers of palpable history: the massive rough-hewn beams that frame the house; an old metal bedstead left here by the Mulfords; antique chests and dressers purchased at local auctions by my brother and his partner; artwork that Mike and I bought during trips abroad; and now, best of all, throws and blankets and shawls I’ve recently knitted. Outside, too, there are perennials I planted just a few years ago, bushes and trees that have flourished since my brother first set them in the ground, a massive Norway spruce we believe to be at least as old as the house.

When my parents left Egypt, they left behind everything they’d grown up with, all the objects that carried their deepest associations and memories. They taught me to scorn such things—what others value as mementos or souvenirs—rightly reasoning they can be lost in a moment. But while we have them, it is lovely, I’m learning, to be grateful for them, to let the spirits embedded within them, the memories and feelings they evoke, surround and comfort us. As I move through this house, I feel bound to my own and others’ histories, lodged in a rich and complex life that nurtures and sustains me. And as I sit still and knit, I sense myself knitting (knotting) up the by now long, loose threads of my own life, shaping them into a coherent and comforting whole.

I am so grateful to have this chance, feeling, as William Wordsworth hoped for himself over two hundred years ago, that my days can now be “bound each to each by natural piety.” To be homebound, I’m learning, can be a gift.

I am so grateful to have this chance, feeling, as William Wordsworth hoped for himself over two hundred years ago, that my days can now be “bound each to each by natural piety.” To be homebound, I’m learning, can be a gift.

Joyce Zonana is the author of a memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey. She served for a time as co-Director of the Ariadne Institute for the Study of Myth and Ritual, and is also literary translator. Her most recent translation is Tobie Nathan’s A Land Like You (Seagull Books), a novel that celebrates the lives of Arab Jews in Egypt in the first half of the twentieth century.

How lovely you are enjoying the quarantine.

The things women have always done. They are more important and more rewarding than we understood when we were young. Of course the division of roles and women’s work was and is overlaid with a large dose of patriarchal control in our world and that may have been what we wanted to escape even without being able to name it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes . . . part of the problem, too, was that those were the ONLY things we were allowed/supposed to do. I can value these things now because I’ve also been able to teach, write, travel, etc . . . not options back then!

AND, another aspect of my longing to escape and my rejection of women’s work was a rejection and devaluing of embodiment–a stance your work has taught us is deeply embedded in patriarchal religious traditions. As we embrace the Goddess, we can value our own bodies and our physical lives in the world.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Such a salient point Joyce – I too was taught that woman’s work was my role in life. It crushed my creativity for many years…

LikeLike

Oh yes, the patriarchal control – I think you are so right Carol. I feared it – and ran away to an island in Maine to escape it – yet I had no idea what I was trying to escape as a 19 year old. That conditioning is still with me cropping up when I am most vulnerable sad to say.

LikeLike

… just lovely Joyce. I so understand your desire to leave, and your appreciation now of domestic life. The story is beautiful: there is joy and calm to be found in the current madness – I will hold this in mind and heart.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for your response Glenys!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Joyce

I’m so happy for you to have found a place that brings you happiness and a peace that you express so well. My home in Danbury where I spent summers as a child has always provided that for me. My wife Susan who you met when we had lunch is suffering thru the final stages of cancer. Being here brings her comfort and the support of my lifelong friends that also live here has eased our pain. I hope you and Mike continue to develop the roots country living can offer.

Lenny

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Lenny for reading and responding. I am so sorry to hear aboutt Susan. Wishing you strength and comfort and peace.

LikeLike

What a beautiful essay, Joyce. Greatly enjoyed reading it and loved the story of your escape.

You escaped your home, and that was a good thing. I hated the city I lived in as a young woman. Three days before my 21st birthday I packed a bag and flew as far as my money would take me, which was London–then and now the city of my heart.

I have not been back to the awful city of my youth in 55 years. I now live in a part of the country mostly populated by “lib’ruls” and I love it.

Also enjoyed the account of your newly discovered affection for the domestic arts. Thank Hestia that many of us have rediscovered them and can now appreciate how essential they are to human happiness.

Happy New Year to you and yours!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you goddessfiction. I was thinking of Hestia as I wrote this. Glad you called her in!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have actually recently returned to my homelands, the place of my birth and growing years, so I could be closer to my mother: I wanted to see her more often (she is 90 and quite well). It is something I thought I would never do; I couldn’t get out of here quick enough after secondary school, and always stressed when I visited. But I enjoy this place so much now – it is beautiful country. I have returned with my partner of 20 years, and he helps my mother too. I know now that I came back as much for myself, as for my Mum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As An Egyptian Citizen, I Apologize To You And All Egyptian Jewish Why Had To Leave Egypt By Stupid Procedures And Unfair Rules . I Need To Tell You That Gamal Abd El -Naser Didn’t Harm Only Jewish But He Badly Affected On All The Egyptians And On Egypt Itself . Egypt And The Egyptians Still Suffer Deeply Suffer From His Political And His System And His Mentality , Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind words, Samy. I believe we will be able to heal that wound of the past, if not in this generation, then in the next.

LikeLike

Beautiful post. Love the photo of your cozy house and the amazing tree!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Elizabeth. It IS an amazing tree!

LikeLike

Such a beautiful moving essay – I love it that you are finding your way home to the grandmothers in every sense of the word. And I love the story. You have discovered such valuable truths and have become a powerful model for others.

Valuing “woman work” comes hard to many of us probably because it is not valued by the culture as a whole. We are conditioned to denigrate or simply dismiss it – I certainly did.

Yet, unlike you, I have always needed home because I never really had one with my parents – and my greatest joy has been in creating a home space regardless of where I was. Fortunately for me, I recognized that my home had to be attached to the outdoors and the forest/water. The one time I rented a space in a local town I withered away in less than two months. The outdoors is an extension of home – here in my woodland cabin that I built (not literally) I am always attached to the outside because of the windows I had put in.

Thank you for sharing your story with us. I hope that many women who read this and feel that constriction will open in a new way.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you for your generous response, Sara. I’ve always loved creating home too, but I always found myself leaving. This is the first time I’ve really, deeply, settled in. And in the country. It’s a revelation!

LikeLiked by 2 people

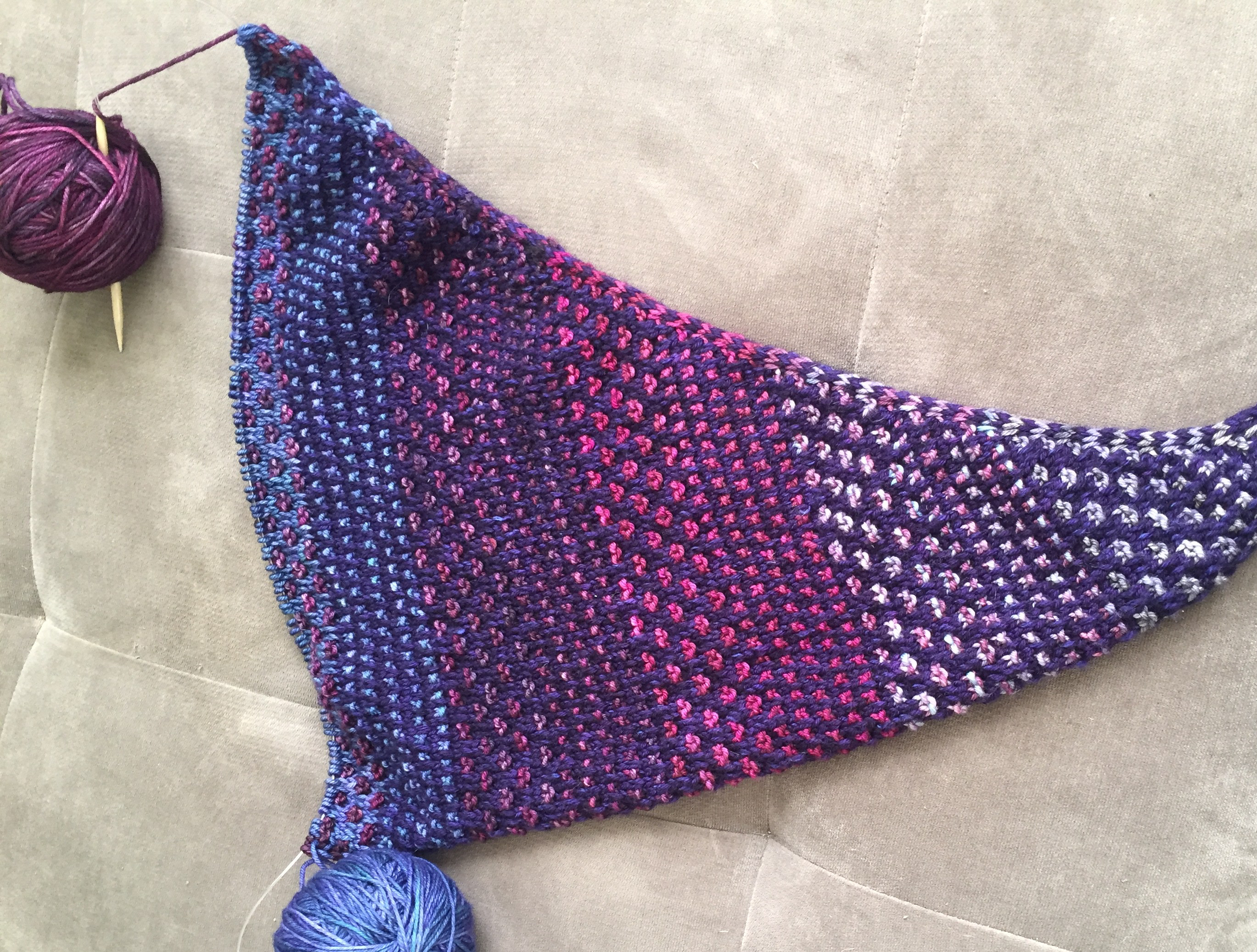

I grew up in a house in Ferguson, Missouri, and escaped to college and graduate school. I haven’t lived in a real house like yours since I was in high school. Your house looks wonderful! And that tree–well, about all I see here in Long Beach are palms and jacarandas and olive trees, so I’m really envious of where you’re staying home. In a house like that, it’s no doubt useful to relearn “women’s work.” And your knitting is beautiful. We’re all doing what we can to endure and survive the pandemic. Thanks for your story! I’m feeling inspired by it. Bright blessings to you and your house. Be safe there!

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thank you so much Barbara! But palms and jacarandas and olives are also beautiful!

Blessings to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, but I miss oak trees. There was a big one in the yard of the house I grew up in. And weeping willows! I was a tomboy and spent my childhood climbing one in a friend’s yard. Ahhhhh, the olden days of fond memories. Thanks again for your touching story. Are you still knitting?

LikeLike

What a beautiful post! Thank you! I’m so glad you have found a home and a joy in the small, simple acts of daily life. I was lucky in that I was never pressured into doing “women’s work” as I was growing up, so I came to see it more as “human work” that everyone does and I am also finding that the daily tasks bring great joy during this time. I can also relate to how living in a historic home enhances your sense of home. I live in a house not quite as old as yours – 150 years old next year. I have done some research and found out little bits about the everyday lives of all the families who have lived here. I do feel their presence and a sense of belonging to a chain of families who have all loved this house and garden and felt connected to the land it is on. May you have a wonderful New Year and continue finding peace and contentment where you are!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, Carolyn. One of my friends recently reminded me that on the Aran it was men who were the knitters traditionally. Yes, we should see all work as “human work,” all important and valuable and potentially beautiful. How lucky for you to live in a house with history as well. It’s such a gift!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am domestically challenged: When I sew on a button, I need to lie down afterwards for twenty minutes to rest from the ordeal. Accordingly, I rebelled against the life of “women’s work” that was just about the only possibility back in my day, and as soon as I could, I took up writing and academics and later married a man who loves to cook. But when we bought our first house, I, like you, discovered spirit and and a sense of connection to the mementos and other objects that I once believed would only enslave me to a life of drudgery taking care of them. So thanks for this lovely reminder, even though I doubt I’ll ever learn to knit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment Barbara! Lucky you to have married a man who cooks. Perhaps he also sews?

LikeLiked by 3 people

He’s better at it than I am.

LikeLike

:-)

LikeLike

I sewed almost all of my clothes from the age of 13 to 21 and then gave up making clothes in graduate school when minis meant I could buy off the rack. I still have my mother’s sewing machine and use it to make repairs and curtains, but not much else. I also was a second mother to my baby brother. When I went away to college I learned that the life of the mind was more important and valued. Yeah like learning that the idea of a table must precede the making of an actual table or that women have a lesser rational capacity than men!!! I am glad I went to college but there was a lot of brainwashing that went on as well.

You say your house has 1 bedroom plus finished attic. Do you know how big the families were who lived in the house? Did they have many children who slept in the attic or on the floor with blankets? As you know my ancestor who farmed in Cherry Ridge PA had 18 children with 2 wives. My ancestors who farmed in Lyons MI had 4-5 children who lived to adulthood. Wondering about the number of rooms in modest farm homes in the east coast.

LikeLike

My mother was a Domestic Science teacher (cooking and sewing), so guess what..? I made sure I was always bottom in both classes at school and sought the life of the mind instead.

I was born and brought up in the country and couldn’t wait to get away to the city but these days miss the countryside more than ever and we are planning to move somewhere rural in the next year.

As a keen knitter, I would say you’re doing some beautiful colour work there, Joyce! Are they your own choice or the pattern?

LikeLike

I want to sit on your swing. It is so lovely to see your joy in knitting.

Also love your theme of finding joys in the quarantine environment we are in.

May you continue to knit together the joys of your life and of your ancestors.

LikeLike

LOVED reading your story! There is a very dear egyptian family I hold close to my heart, the woman moved here when she was just a teenager! Her father helped spread Christianity in Egypt. Your knitting is beautiful!

LikeLike

Hi Joyce — I enjoyed your post, especially as it relates to finding ways to enjoy the quarantine that has been imposed on us by COVID. For me, that has meant writing stories for my 3-year-old grandson.

When it comes to women’s work, like you, I rejected it as patriarchally imposed domesticity. But I reevaluated that rejection when I started to teach Women’s Studies in the mid-1970s. I never took women’s crafts up, but when I taught the Women and the Arts class, I brought in a quilter and woman who researched the arts and crafts movement of the early twentieth century. I treasure my grandmother’s afghans (knitted). But I still dislike sewing (not as much as barbaramchugh) and cooking. Fortunately, I (like Barbara again), I married a man who loves to cook and cooks really well.

I come from Upstate New York. Where are you living now?

LikeLike