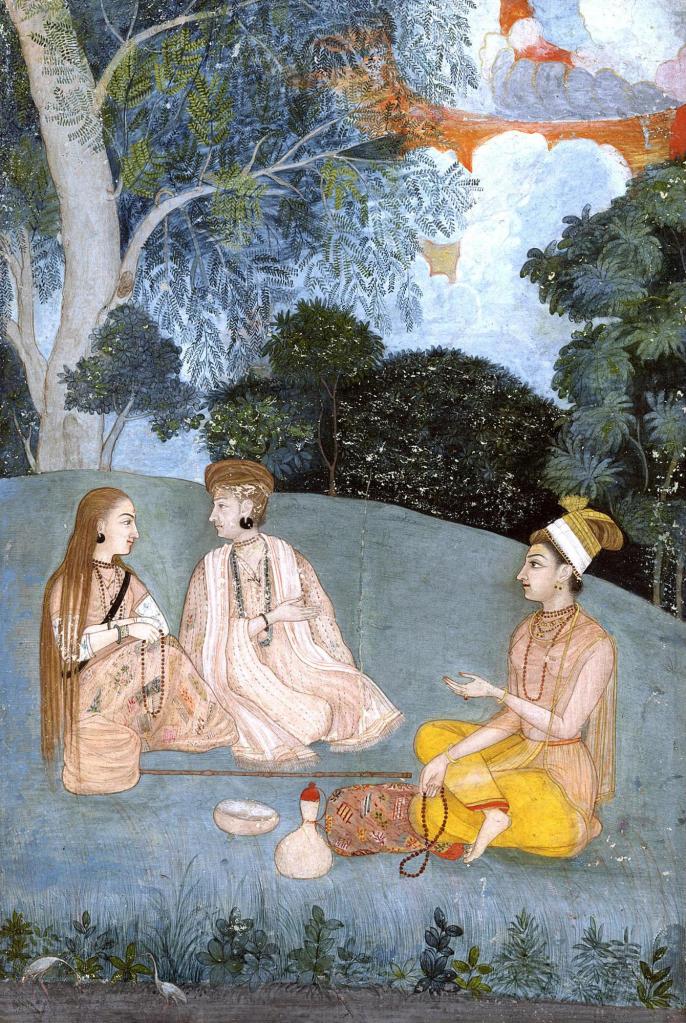

Painting of a noblewoman seeking counsel from two Tantric yoginis, in the Mughal style, about 1750. From the British Museum’s recent exhibition, Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution. A beautiful starting point to learn about Indian spirituality in its original context. May all our paths be crossed by wise teachers.

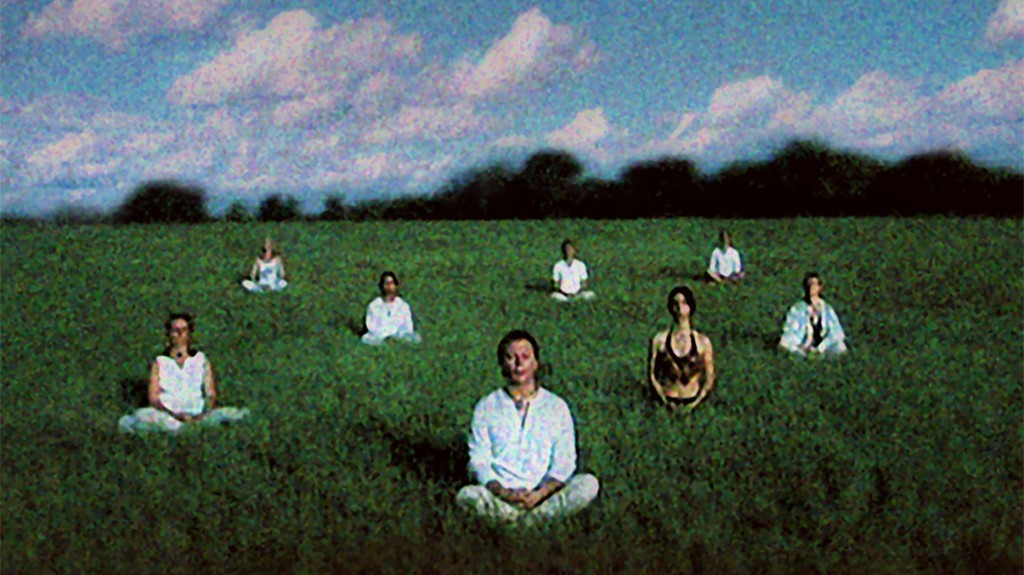

I’ve received a tremendous response to my essay on cults, published on Feminism and Religion in December last year. The topic continues to be a burning issue as more and more survivors break their silence on the spiritual abuse they suffered. Cults are a feminist issue because women and girls suffer the worst abuses at the hands of male cult leaders.

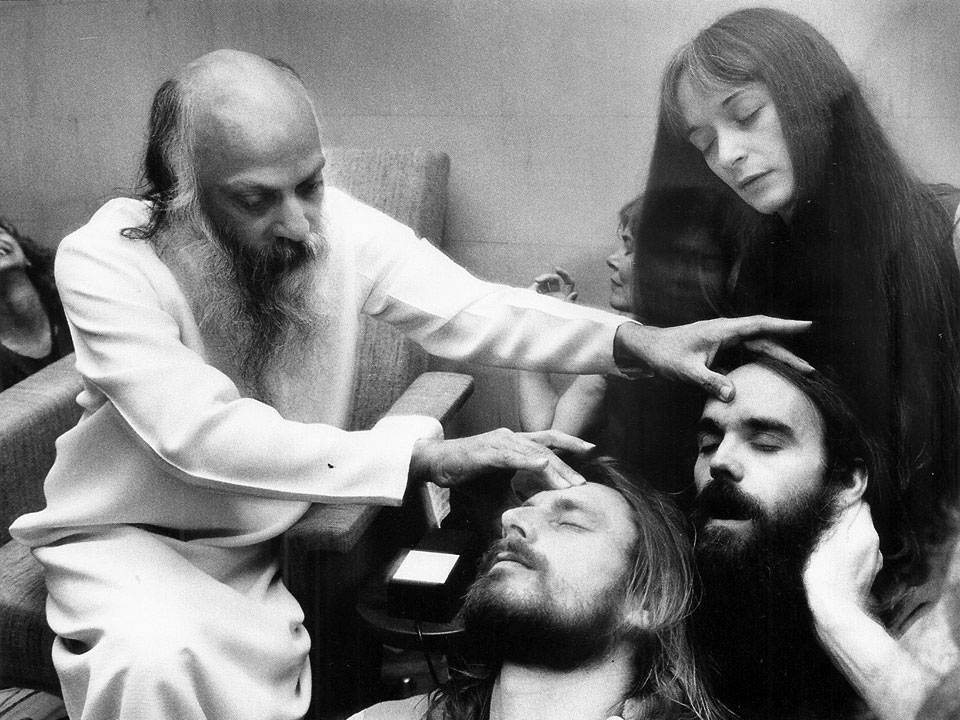

To fully understand how this cult dynamic works, I highly recommend watching Dan Shaw’s lecture on the subject, in which he explains how cult leaders are traumatizing narcissists whose goal is to subjugate their followers and “purify” them by utterly destroying their sense of self. Yet for me, the most haunting moment of his presentation came just near the end, during the Q & A session. An audience member and survivor of Siddha Yoga, the same cult that Shaw once belonged to, asked, “Are there gurus that people can trust?” She asked if guru-driven spirituality was “inherently subjugating.”

Shaw, perhaps understandably not wanting to come across as a white man casting judgement on another culture’s deeply-rooted spiritual traditions, wiggled out of answering by saying that it was up to the individual to discern if a particular guru was safe or not.

But I think this anonymous woman’s question deserves a more nuanced answer.

In Hinduism, since the age of the Upanishads, gurus have played a crucial role in preserving wisdom teachings in a religion with no centralized authority figure or governing body. The teachings are passed on orally to disciples who worship the guru as a divine being in order to realize their own innate divinity. I would love to hear from Indian feminists on how this guru-disciple relationship plays out in India today, particularly with female practitioners.

However legitimate and honorable these systems might be in their original cultural context, I think it’s fair to say something gets lost in translation when Eastern spirituality moves West. Great abuses have come to light. Katy Butler, in her article, “Encountering the Shadow in Buddhist America,” writes that guru abuse has become so prevalent due to the “unhealthy marriage of Asian hierarchy and American license that distorts the student-teacher relationship.”

It’s pertinent to point out that many of these misbehaving gurus, lamas, and swamis are white men. Spiritual hierarchies can be abusive across cultures—look at the sex abuse scandals in the Catholic Church. Cults are not necessarily “Eastern” or “foreign.” There are plenty of Christian cults, self help cults, and wellness cults.

Another thing that often gets lost in translation is what Eastern spirituality actually intends to offer the student. Many Western students turn to Eastern disciplines like meditation and mindfulness for stress reduction, but that is not their original purpose. These disciplines are intended to liberate the practitioner from the wheel of death and rebirth, to transcend this world of suffering and our worldly attachments, in order to enter an enlightened state—i.e. not to be reincarnated again, a goal some Western people might find world-denying and nihilistic.

Dr Willoughby Britton, professor of psychiatry at Brown University, speaking to Rachel Bernstein on IndoctriNation podcast asks, “How problematic or paradoxical is it if you believe that enlightenment is a destination that someone else can take you to? What dependence does that create?”

The goal is unmeasurable and the endpoint keeps shifting according to the power dynamics. You become much more dependent on the teacher who decides if you have reached this invisible destination. If you’re being charged a lot for the teachings, the teacher may decide that you don’t achieve the end result for a very long time.

Willoughby says practitioners can empower themselves by asking themselves the following questions:

Where do you want to go with this practice?

If you are seeking enlightenment, what does that mean for you?

You get to define your own outcomes and measure your success by what you want to show up in your life, i.e. better sleep, reduced anxiety, improved relationships, and inner peace.

In evaluating teachers and spiritual groups, ask yourself:

What were you initially promised?

Has it been achieved after all your hard work?

Do you feel you are closer to your goal?

Or have your initial reasons been shifted by the teacher into their reasons and their goals that are no longer yours?

Are you under pressure to perform for and please the teacher?

Are you expected to use scripted, stilted language to describe your experience?

If you question the teacher and the teacher retaliates, that’s your tipping point, says Britton. If you say that a practice isn’t working for you and the response you get is, “Well, that’s because you don’t have the right karmas/aren’t dedicated enough/haven’t reached the right level of spiritual maturity” etc., you need to leave and find a different group.

In order for anyone to have a healthy experience with a teacher, you need the freedom to say, “I think this isn’t working for me, and, in fact, it’s hurting me and I need to move on.” Depending on how people respond to you setting your boundary, you’ll know if you’re in a healthy space or not.

As Dan Lawton says on another episode of IndoctriNation Podcast, a spiritual practice can only be as healthy as the person teaching you that practice. The endgame for a lot of teachers is often building a personal brand around the supremacy of a certain spiritual practice. Once you’re locked into that box, there are a lot of things you’re not going to be able to see and there’s a possibility of doing real harm to your students.

Good, ethical teachers, whether they call themselves gurus or not, are deserving of deep respect. But they need to be vetted and held accountable. And maybe in the West, at least, the obligation to see the teacher as enlightened or divine is indeed too subjugating. Maybe it would much healthier to look up to them as a wise elder or mentor. Surrendering our agency to another human is always going to be subjugating.

Perhaps we can follow the example of the female seeker in the 18th century painting above, who is taking counsel from two yoginis, female practitioners who live in the forest, outside the strictures and hierarchies of patriarchal society. Instead of placing all our hopes in one exalted individual, why not instead seek the deep wisdom of the female collective?

Mary Sharratt is committed to telling women’s stories. Please check out her acclaimed novel Illuminations, drawn from the dramatic life of Hildegard von Bingen, and her new novel Revelations, about the mystical pilgrim Margery Kempe and her friendship with Julian of Norwich. Visit her website.