I recently assigned my students an article by Kathleen Erndl – “Is Shakti Empowering for Women? Reflections on Feminism and the Hindu Goddess.”[1] I’m sure, like Erndl, many have been fascinated by this question, especially within the Indian context. Does the presence of an abundance of goddesses necessarily translate to social empowerment for women? The answer is indeed complicated in that one cannot reify all goddess worshippers under one static rubric.

I recently assigned my students an article by Kathleen Erndl – “Is Shakti Empowering for Women? Reflections on Feminism and the Hindu Goddess.”[1] I’m sure, like Erndl, many have been fascinated by this question, especially within the Indian context. Does the presence of an abundance of goddesses necessarily translate to social empowerment for women? The answer is indeed complicated in that one cannot reify all goddess worshippers under one static rubric.

Having said that, however, I would like to posit that generally speaking, it would be fair to say Indian culture is a patriarchal one, and that the presence of a goddess tradition does not translate to independence for women. Firstly, the kind of goddesses worshipped by both men and women, are not necessarily the assertive, independent kind. They are often those such as Lakshmi and Saraswati who are maternal and nurturing, and important in their own right. All too often, however, these virtuous traits have been used to disempower women, to keep them in their “socially assigned places.”

There is evidence from early Hindu literature that the above goddesses may initially have been independent forces, but they soon came to be tamed as consorts of male gods; Lakshmi as Vishnu’s wife, and Saraswati as Brahma’s. Second, fierce and independent goddesses such as Kali and Durga may have a large following, but it is only in certain cases such as in Tantric theology specific to the goddess Shakti, identified with Kali, that ritual practices may do away with gender roles, that both male and female members have equal access to Kali. But the important question would be – outside of the ritual context, how do practitioners of Tantra regard women? In other words, do women have equal social – and not merely equal ritual – status? I am not an expert in Tantric discourse, but judging by various commentaries, I have reason to believe that this does not necessarily translate to gender equality in the social setting.

My quest here, however, is to provide an example of what a community with a strong, female leader may look like. I thought of this example because I have been intrigued with and fascinated by my own family experience regarding the cult of Kalawati Aai or Mother Kalawati (I do not use the term “cult” derogatorily as “a group with a powerful and controlling leader” but in the classical sense of “practices centering on an object of reverence”). My aim is to provide a picture of often conflicting ideals within the Hindu setting, to shed light on how this can play out on the ground. My information on Kalawati Aai – considered a saint by her devotees – comes from hearsay and hagiographical accounts for I never met her; she died almost forty years ago.[2]

Continue reading “Was Mother Kalawati a Feminist? (Part 1) by Vibha Shetiya”

In 2003, I picked up a collection of essays on little known Ramayanas. Buried within was a poem by Pathabhi Rama Reddy. Pathabhi, a rebel of Telugu literature, defied not just conventional rules of grammar but also those of popular thinking, best exemplified by his poem, “Sita,” the subject of this post.[1]

In 2003, I picked up a collection of essays on little known Ramayanas. Buried within was a poem by Pathabhi Rama Reddy. Pathabhi, a rebel of Telugu literature, defied not just conventional rules of grammar but also those of popular thinking, best exemplified by his poem, “Sita,” the subject of this post.[1]

Continued from

Continued from  I recently assigned my students an article by Kathleen Erndl – “Is Shakti Empowering for Women? Reflections on Feminism and the Hindu Goddess.”

I recently assigned my students an article by Kathleen Erndl – “Is Shakti Empowering for Women? Reflections on Feminism and the Hindu Goddess.” One of the most exciting times of the semester occurs when we watch “Sita Sings the Blues” in class. This film by Nina Paley – one she has made available to the public by withholding copyright – is a wonderful addition to what has come to be known as the Ramayana tradition. Unlike a few decades ago when scholarship focused on only pan-Indian literary Ramayanas, scholars today are beginning to acknowledge that most people get to know of Rama and Sita through folk and oral tales, women’s songs and local and regional tellings.

One of the most exciting times of the semester occurs when we watch “Sita Sings the Blues” in class. This film by Nina Paley – one she has made available to the public by withholding copyright – is a wonderful addition to what has come to be known as the Ramayana tradition. Unlike a few decades ago when scholarship focused on only pan-Indian literary Ramayanas, scholars today are beginning to acknowledge that most people get to know of Rama and Sita through folk and oral tales, women’s songs and local and regional tellings. We have been hearing a lot about Kali and Durga lately, manifestations of the great goddess (“

We have been hearing a lot about Kali and Durga lately, manifestations of the great goddess (“

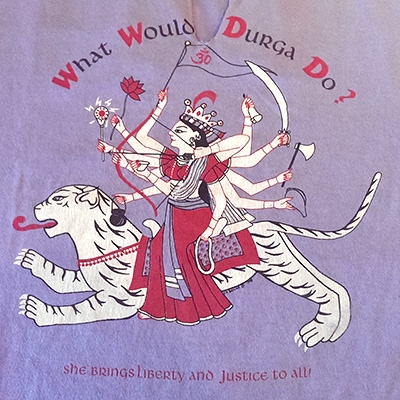

It’s one of my favorite T-shirts. Every time I wear it, people who know who Durga is comment. So do some people who don’t know who the Hindu goddess is.

It’s one of my favorite T-shirts. Every time I wear it, people who know who Durga is comment. So do some people who don’t know who the Hindu goddess is. In contrast to the linearity of our time concept in the West, Indians view life as infinite and cyclical. Although Hindus, like ancient Greeks, believe in four ages of humanity (the so-called yugas), these occur not just once, but repeat cyclically every several million years. Similarly, the creator god Brahma is said to have a daily cycle which has recurring effects on the existence of the world. When Brahma awakes the world is created anew, and when he falls asleep it dissolves once again into the primal waters of eternity. Fortunately for us, Brahma’s day lasts 4,320,000,000 human years.

In contrast to the linearity of our time concept in the West, Indians view life as infinite and cyclical. Although Hindus, like ancient Greeks, believe in four ages of humanity (the so-called yugas), these occur not just once, but repeat cyclically every several million years. Similarly, the creator god Brahma is said to have a daily cycle which has recurring effects on the existence of the world. When Brahma awakes the world is created anew, and when he falls asleep it dissolves once again into the primal waters of eternity. Fortunately for us, Brahma’s day lasts 4,320,000,000 human years. Ramakrishna was one of the major poets who popularized Kali’s worship in Bengal, the northeasternmost province of India. Born in the early part of the 19th century, he was a Hindu saint in a tradition known as bhakti, where devotees lovingly surrender their hearts, minds and spirits to their chosen deity in a practice which leads to ecstatic union with the divine. Such devotion is easier for us in the West to imagine when the beloved is the playful Krishna with his sublime flute-playing and sacred lovemaking. But in Ramakrishna’s case, the object of his devotion was the fierce Kali, the wild and uncontrollable aspects of the sacred, to whom he devoted himself as a child would to its mother.

Ramakrishna was one of the major poets who popularized Kali’s worship in Bengal, the northeasternmost province of India. Born in the early part of the 19th century, he was a Hindu saint in a tradition known as bhakti, where devotees lovingly surrender their hearts, minds and spirits to their chosen deity in a practice which leads to ecstatic union with the divine. Such devotion is easier for us in the West to imagine when the beloved is the playful Krishna with his sublime flute-playing and sacred lovemaking. But in Ramakrishna’s case, the object of his devotion was the fierce Kali, the wild and uncontrollable aspects of the sacred, to whom he devoted himself as a child would to its mother.