This was originally published on September 9, 2015

This essay is inspired by Donna Henes’s brilliant post, I am Mad. Too often as spiritual women, we are told we have to perform niceness all the time, even if it means compromising our boundaries and principles.

Mainstream religions tell us we must forgive those who mistreat us. Too many women in very abusive situations literally turn the other cheek–to their extreme detriment. As Sherrie Campbell points out in her essay The 5 Faults of Forgiveness, the obligation of forgiveness oppresses survivors of abuse because it makes it all about the perpetrator and not about the healing, dignity, or boundaries of the survivor.

In my own Catholic upbringing I learned to swallow my anger and rage until it erupted in depression and burning bladder infections. My background did not teach me to skillfully dance with anger and it’s been a difficult learning curve for me. But I learned the hard way that owning my anger was crucial if I wanted to stand in my power and speak my truth.

Once when I felt a particularly strong need to break out of a dysfunctional situation, I had a powerful dream of a black snake, as beautiful as it was terrifying. In the course of the dream, I realized that the huge black snake was my own repressed anger, power, and strength. The beautiful inner self longing to be claimed.

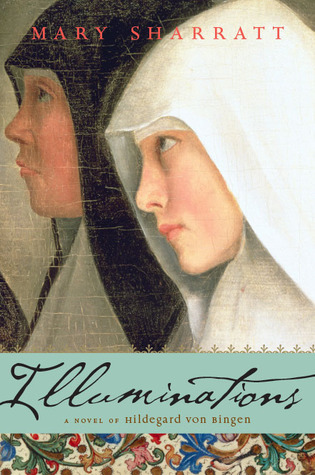

Meek and mild women don’t make history. Hildegard von Bingen, whose feast is coming up on September 17, famously spoke her mind and ferociously stuck up for what she thought was right, famously locking horns with Emperor Barbarossa himself. She also defied her archbishop and suffered an interdict as a consequence, nearly dying an excommunicant. But she was a strong woman who would not be silenced. We should all be so brave and bold.

Claiming our true spiritual power means claiming each part of ourselves, including our fierceness. Our scary side.

Fierceness means embracing our gut wisdom. Voicing the sacred NO to protect ourselves and our loved ones from compromising situations.

I see modern day women like holistic healer Susun Weed embodying this fierceness as she empowers women and girls to recognize the sacredness of their own bodies, the holy mysteries inherent in menstruation, childbirth, and menopause, which are too often pathologized in male-dominated medicine.

Over the years I’ve learned to trust and act on my own inner knowing and discernment. To know when to say NO. By using strong, no bullshit women like Hildegard and Susun Weed as my role models.

Each time I trusted myself enough to act on my gut wisdom, to trust the inner NO, and speak my truth, it has served me well, although it’s sometimes been a painful learning process.

Anger and fierceness wake us up to what is wrong and needs to be changed. There is so much energy in anger that can be harnessed for healing and transformation. Fierceness is the strongest, most protective form of love, the ferocity with which a mother bear defends her cubs.

Coiled inside each one of us is a snake of great power. Let us all dance in our power and strength.

Minoan Snake Goddess, ca 1600 BCE, Knossos, Crete

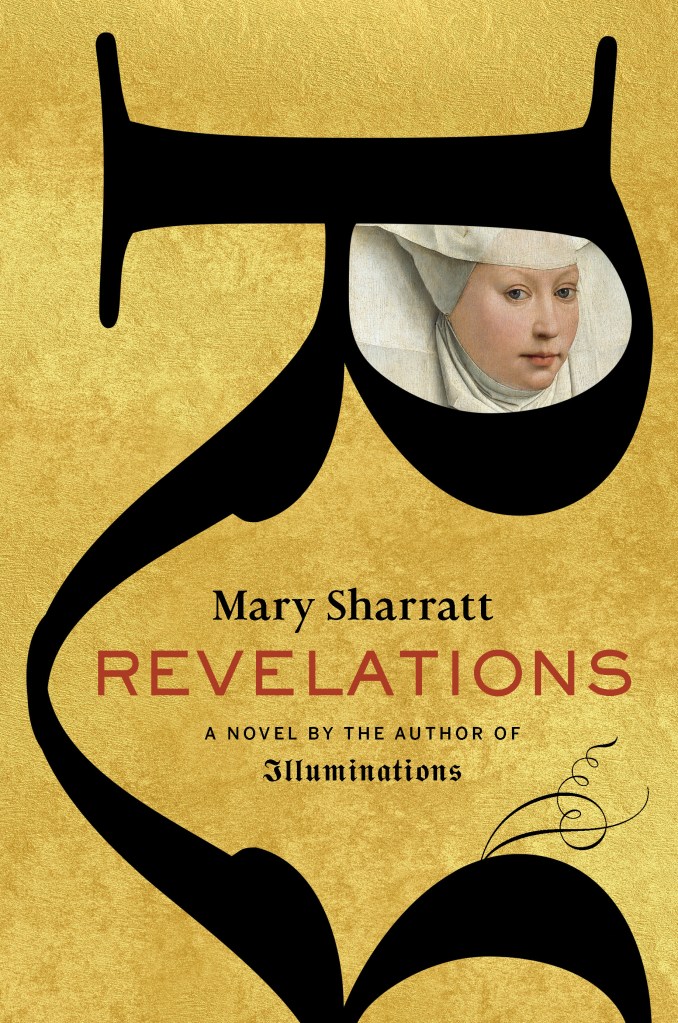

Mary Sharratt is committed to telling women’s stories. Please check out her acclaimed novel Illuminations, drawn from the dramatic life of Hildegard von Bingen, and her new novel Revelations, about the mystical pilgrim Margery Kempe and her friendship with Julian of Norwich. Visit her website.

Mary Sharratt is on a mission to write women back into history. Her acclaimed novel

Mary Sharratt is on a mission to write women back into history. Her acclaimed novel

When I was about eight years old, I dreamed one night that I stood inside the workings of an immense instrument, so big it filled the sky. It was crafted of wood and gold, and although there was no obvious source of light, it was brightly illuminated. I could have confused it for the inner workings of a clock except that I could hear the sweet music it produced resonating throughout its cavernous hollows. It was curious to me that there seemed to be no atmosphere there either to breathe or to carry sound. Within it, I did not perceive any movement. And, there was no actual melody that it produced, which could be sung or repeated. There was only an enveloping harmonic thrumming. The sound was multiplicative and voluminous although not piercing. I understood it in the dream to be cosmic, structural, primordial, and generative. When I awoke, I had the feeling that I had seen something divine. It was not heaven. It was not God. It was more like the instrument of the universe, or the universal instrument, created as a first work among creation

When I was about eight years old, I dreamed one night that I stood inside the workings of an immense instrument, so big it filled the sky. It was crafted of wood and gold, and although there was no obvious source of light, it was brightly illuminated. I could have confused it for the inner workings of a clock except that I could hear the sweet music it produced resonating throughout its cavernous hollows. It was curious to me that there seemed to be no atmosphere there either to breathe or to carry sound. Within it, I did not perceive any movement. And, there was no actual melody that it produced, which could be sung or repeated. There was only an enveloping harmonic thrumming. The sound was multiplicative and voluminous although not piercing. I understood it in the dream to be cosmic, structural, primordial, and generative. When I awoke, I had the feeling that I had seen something divine. It was not heaven. It was not God. It was more like the instrument of the universe, or the universal instrument, created as a first work among creation

Hildegard, who lived from 1092 to 1179, was the tenth child of a family of minor nobility in the Holy Roman Empire. She’s a sturdy child who loves the outdoors and enjoys running through the forest with her brother. But early in the novel, she learns that she is to be her family’s tithe to the church. Her mother has already arranged for this bright and curious eight-year-old child to be the companion to Jutta von Sponheim, a “holy virgin” who yearns to be bricked up as an anchorite in the Abby of Disibodenberg. Being an anchorite means that, like Julian of Norwich (about 250 years later), this girl and her magistra are bricked in. There is a screened opening in the wall through which their meager meals are passed and through which they can witness mass and speak to Abbott Cuno, the other monks, and visiting pilgrims, but they can never go out. Never. In the Afterword, Sharratt writes that “Disibodenberg Abbey is now in ruins and it’s impossible to precisely pinpoint where the anchorage was, but the suggested location is two suffocatingly narrow rooms and a narrow courtyard built on to the back of the church” (p. 272). As Sharratt vividly shows us, Hildegard survived in that awful place for thirty years.

Hildegard, who lived from 1092 to 1179, was the tenth child of a family of minor nobility in the Holy Roman Empire. She’s a sturdy child who loves the outdoors and enjoys running through the forest with her brother. But early in the novel, she learns that she is to be her family’s tithe to the church. Her mother has already arranged for this bright and curious eight-year-old child to be the companion to Jutta von Sponheim, a “holy virgin” who yearns to be bricked up as an anchorite in the Abby of Disibodenberg. Being an anchorite means that, like Julian of Norwich (about 250 years later), this girl and her magistra are bricked in. There is a screened opening in the wall through which their meager meals are passed and through which they can witness mass and speak to Abbott Cuno, the other monks, and visiting pilgrims, but they can never go out. Never. In the Afterword, Sharratt writes that “Disibodenberg Abbey is now in ruins and it’s impossible to precisely pinpoint where the anchorage was, but the suggested location is two suffocatingly narrow rooms and a narrow courtyard built on to the back of the church” (p. 272). As Sharratt vividly shows us, Hildegard survived in that awful place for thirty years.