Wren, the first bird to sing at dawn, is known as the Herald of Dawn. It calls out its joy as each day begins.

Wren, the first bird to sing at dawn, is known as the Herald of Dawn. It calls out its joy as each day begins.

Fairy tales are intwined in our imagination and our spirituality. As Jane Yolan writes, one of the subtlest and yet most important functions of myth and fantasy is to “provide a framework or model for an individual’s belief system.” (1)

In the Reclaiming spiritual tradition, we often use fairy tales in healing and self development work. These stories act as warp and weft as we weave and spin complex ritual arcs and other events that take place at extended Witch Camp sessions. In Twelve Wild Swans, Starhawk points out that fairy stories are “more than just encouraging and inspiring. They are also templates for soul healing from Europe’s ancestral wise women and healers. When the ancient Earth-based cultures of Europe were destroyed, these stories remained.” (2)

Continue reading “Sleeping Beauty: An ancient tale for these challenging times by Diane Perazzo”Note: If you’ve been reading Athena’s story for the past two days (link to Part 2 here), you know what’s happened to her before her third birth. You’ve read her version as I heard it in my mind and wrote it down. Part 3, here, is mostly speculative, based on hints in books I’ve read during the past twenty-plus years. If you’ve read The Greek Myths by Robert Graves (who is said to be The Authority), you’ve met Medea in the context of the yarn about the Golden Fleece, but I’m leaving Jason out of this story. I’m also leaving Theseus (also associated with Medea) out. These boys have no role in Athena’s story of her meeting and her shamanic rebirth at the hands of the great Medea, who is sometimes called a sorceress. Read on.

And so with the help of the great Hera, who remembered how I had once loved her (and she still loved me), I left Zeus’ stony kingdom. Hera helped me depart, though I soon forgot her help. I suppose she is still there. After all, her own lands had been taken long before, her own throne stolen long ago, her temples and altars supplanted. I suppose she has nowhere to go now. For all I know, great Hera remains at the declining god-king’s side, where poets still deprecate her and laugh at her and call her a nagging wife. A god-king as impotent as he is now needs such a strong wife, does he not? I regret that I no longer know her.

But I could find no other kingdom that would give me charity or honor, found no other king or god who would wed me or let me speak for him, and so I become disillusioned with kings and gods and epic tales. I put down my spear and shield and abandoned my armor and helmet, though I always kept my owl (who often flew above me) and my ragged plume.

And so, twice homeless, twice born and twice dead, friendless and scorned by the men I had so harshly judged, I wandered through the world, and all anyone saw was a woman, a gray, anonymous woman carrying a stick and a drooping feather. I walked up and down in the world and had no home. I had neither friends nor sisters nor protégées to honor me, neither priestesses nor queens to love me. I had no one at all. I had nothing at all. I wandered alone through all the lands around the wine-dark sea, alone in the lands around the central sea, alone in the lands along the ocean sea and the northern sea. For uncounted years I wandered alone, stopping here and there, but never staying anywhere, searching for what I never found and no longer remembered. I went in a plain gray cloak with my stick in my hand, my sad plume in a pouch at my belt. Sometimes I ate, but more often I went hungry. Up and down upon the earth I walked, and so my pride and anger began to be worn away.

Continue reading “Thrice-Born Athena, Pt. 3 by Barbara Ardinger”Read Part 1 here.

Note: This part of the story concerns what nearly everybody who has read the mythology knows about the Goddess of Wisdom. But what you’ve read in, say, Edith Hamilton or Robert Graves is the patriarchal version. What would the story be like if Athena told it herself? That’s what I imagined as I wrote her story. Read on to learn more about her Greek incarnation.

After our tribe was conquered by the warriors who lived across the seas, I wished to die, and I was indeed close to death when I was carried off by the bloody hero who fancied me. I longed to die every time he violated my body, every time he crushed my mind. But I was carried away alive, a living trophy for that warrior-king. I was secured in his warship as it sailed across the sea to his hard and stony land. Weak though I was, men still fought over me. Eventually I was claimed by their god-king Dyaus, whom you may know by his commoner name, Zeus. I was claimed as his prize of war, dragged up the stony mountain that came to be called Olympus, and flung into his harem until I should become strong enough to bear his weight upon me in mating. And still I longed to die.

Continue reading “Thrice-Born Athena, Pt. 2 by Barbara Ardinger”

Note: Inspired by Mary Sharratt’s excellent post on February 13 about the heroine’s journey and by Elizabeth Cunningham’s beautiful novel The Wild Mother (who is Lilith), I took a dive into my archives and found this story about Athena, which I first wrote back in the late 1980s. That was about the time the Goddess rapped me on the head, so to speak, and said, “Pay attention.” The story is based on research I did at the time. I’ve now done some rewriting for FAR. Read on and hear the voice of Athena not as a player in the usual Greek myths but as a goddess of wisdom who is one-unto-herself.

My first birth was in the dark continent to the south of the Black Sea, always described by Homer (who invented much of what you take as true in his two long stories) as the wine-dark sea. That is, I was born in what is now Libya in northern Africa. I was born in a many-chambered palace beside a clear lake and received into the world by a tribe of strong women. I was the first-born child of Metis the Wise. You may have read that Metis was the daughter of Oceanus and a Titaness of great cunning; that’s what the “traditional wisdom” says about her. Not true. Metis was one-unto-herself, the queen of a great tribe, holder of the sacred serpents, and painter of wild scenes on tall red cliffs that exist into your day. I was the daughter of daughters from the beginning of the earth, whom some have called Amazons. I knew nothing of that name, however, for I was simply a much beloved child of a thousand thousand foremothers and a hundred living mothers.

Continue reading “Thrice-Born Athena: A Secret History (Part 1) by Barbara Ardinger”

Rabbit plays in tall grasses, dances in the moonlight, nibbles on nature’s greens, then freezes if danger is sensed. With a thump as a warning, rabbit hops away in a flash, disappearing down its rabbit hole.

Rabbit plays in tall grasses, dances in the moonlight, nibbles on nature’s greens, then freezes if danger is sensed. With a thump as a warning, rabbit hops away in a flash, disappearing down its rabbit hole.

Continue reading “Rabbit, The Feminine, and The Moon by Judith Shaw”

Consider the following four birth stories:

Continue reading “Aren’t We All Divine Children? by Janet MaiKa’i Rudolph”

Recently, I wrote a novel about the Buddha’s wife disguising herself as a man to join his religious community. When I showed the manuscript to a Buddhist friend, whose knowledge and practice I respect greatly, he expressed apprehension that it violated the basic myth of Buddhism. I assumed he meant that my storyline of gender deception strays too far from the versions of the Buddha’s life as recorded in the traditional canon, which adherents regard as the Buddha’s inviolable teachings. The last thing I wanted to do was to misrepresent these teachings.

What does it mean “to violate a myth”? If I had portrayed the Buddha as a psycho-killer or wife-beater, I could appreciate this charge, but I had presented an enlightened Buddha whose values were in alignment with standard scripture and the mores of his day. The change I made was to tell the story from a woman’s point of view, and to do so, I modified some of the traditional legends and created new material to make my choices plausible. Predictably, my modifications came up against many of the stories’ misogynistic elements.

Continue reading “Buddhist Misogyny Revisited – Part I by Barbara McHugh”

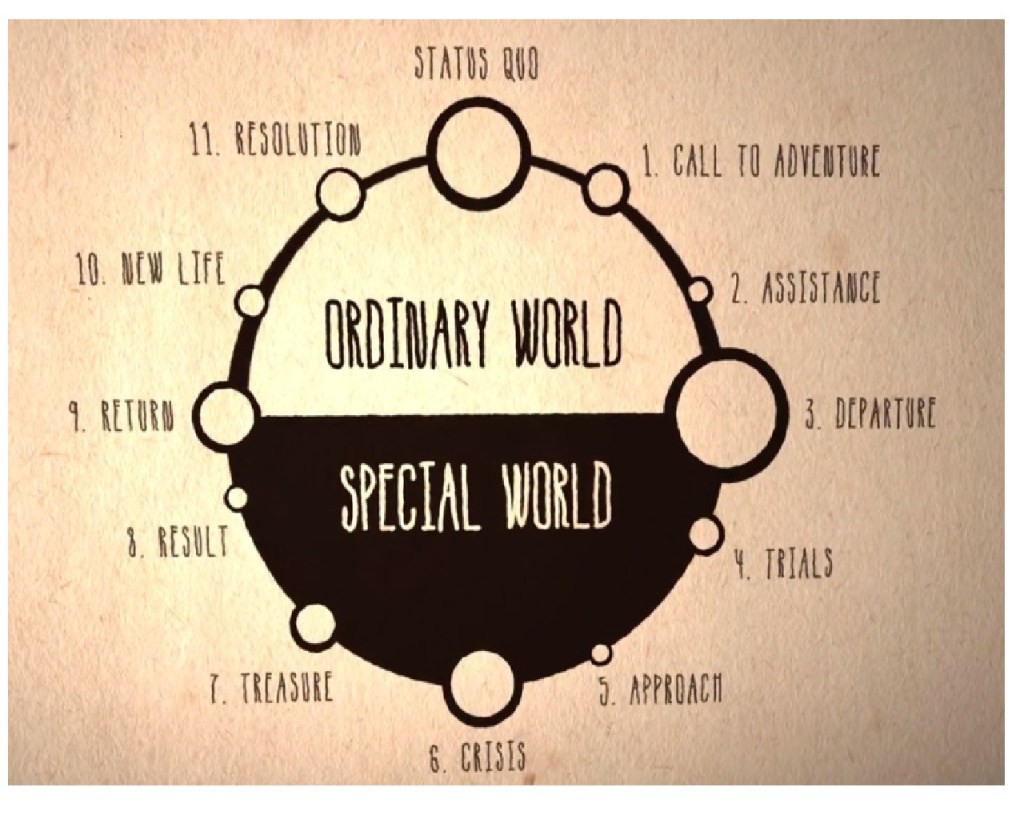

Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, the Hero’s Journey, is outlined in his 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Drawn from his studies of comparative mythology and Jungian psychology, the Hero’s Journey has become a foundation myth of modern culture. The hero, generally young and vigorous, sets off into the unknown to battle antagonistic forces and returns transformed, a hero and guide to his people.

As Campbell writes in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

The Hero’s Journey has served as the go-to template for Hollywood screenwriters and bestselling novelists. We see this mythic pattern of the conquering male hero played over and over again in popular culture. Think Luke Skywalker in the original 1977 Star Wars—or any protagonist in a George Lucas or Steven Spielberg movie. Creative writing teachers encourage their students to pattern their story arcs on the Hero’s Journey to give a sense of archetypal depth and resonance. But this technique has been overused to the point of becoming a cliché. A deeply sexist cliché. Continue reading “The Via Feminina: Revisioning the Heroine’s Journey by Mary Sharratt”