Vanessa Rivera de La Fuente is Muslim, feminist, and a human rights activist

Photo: Personal archive

Background: Journal O ‘Globo, one of the most important newspapers in Brazil, belonging to the transnational media group of the same name, published this interview with Vanessa Rivera de la Fuente on Islamic Feminism. Given its relevance to the discussion on the subject, it was translated by prominent Islamic feminist and scholar Keci Ali to share it with English-speaking readers.

The Muslim women’s movement has different agendas in accordance with the reality of each country. In Latin America, the Muslim Vanessa Rivera fights against prejudice about Islam.

by Isabela Aleixo*

Vanessa Rivera de La Fuente is Chilean and Muslim. Besides being an academic researcher, she’s also an Islamic feminist engaged with questions of gender, human rights, and social development. Vanessa has wide experience in social projects in Latin American countries.

In an interview with CELINA, she discusses the prejudices that Muslim women face in Latin America, explains the movement’s demands, destroys stereotypes, and declares: “I’m a woman and I demand to be treated as a person.”

Do you consider yourself an Islamic feminist? Why?

I consider myself a feminist woman, who lives feminism in all the distinct facets of her life: I’m Muslim; I’m a single mother; I’m a professional woman, an academic; and I’m a women’s rights activist. I’m feminist with all my life experiences. I think being a woman in male-dominated society is itself a political fact, so everything that I am as a woman can be resignified by feminism, including being Muslim. Islam is integrated into my life and my political struggle, which is intersectional. It’s based on the radical idea that all women are people and we deserve equal rights and a world free of violence.

Continue reading ““If All Knowledge Must be Reinterpreted, Why Not Religion?” Says Islamic Feminist”

I was once asked “why do I stay Muslim”? That was the question prompt, and it begged an answer…Reason #2: I believe Islam has vagueness in the Quran (I answered

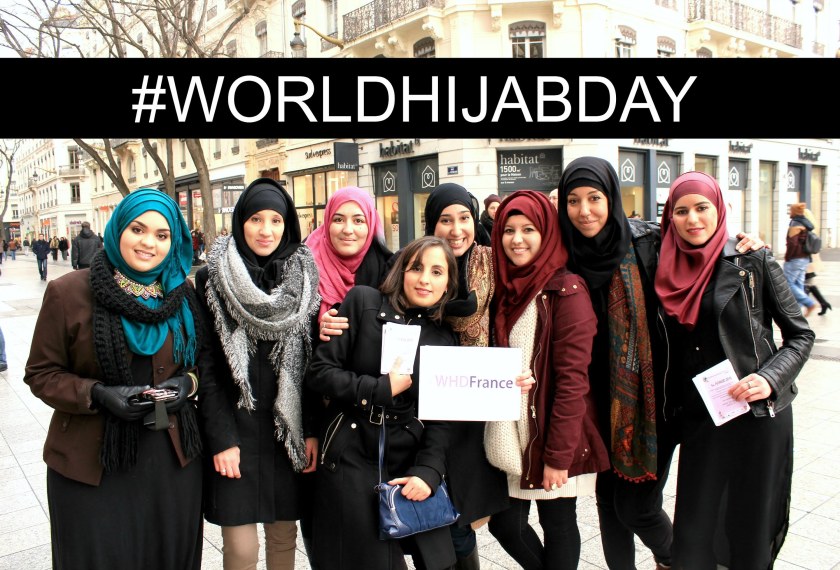

I was once asked “why do I stay Muslim”? That was the question prompt, and it begged an answer…Reason #2: I believe Islam has vagueness in the Quran (I answered  When World Hiyab Day (WHD) was held for the first time in 2013, I was an enthusiastic supporter. Even my friend Maria de los Angeles from Venezuela, wore a headscarf for a day in sisterhood. She went to her job and celebrated her birthday in a tropical country, fully head-covered.

When World Hiyab Day (WHD) was held for the first time in 2013, I was an enthusiastic supporter. Even my friend Maria de los Angeles from Venezuela, wore a headscarf for a day in sisterhood. She went to her job and celebrated her birthday in a tropical country, fully head-covered.

When I was growing up in 1950s Bensonhurst, in Brooklyn, NY, my identity as a Jew was often called into question. “You mean you’re Jewish? And you don’t know about gefilte fish?” my best friend’s Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish mother asked, shocked to discover that our family ate stuffed grape leaves rather than stuffed cabbage. “What kind of a Jew are you?” schoolmates challenged. When I answered “Sephardic . . . from Egypt,” they would reply. “But all the Jews left Egypt a long time ago, isn’t that what Passover is about?” “No,” I would say, having been taught the words by my father. “Some Jews returned to Egypt when they were expelled from Spain.” [Later I would learn that some Jews actually lived in Egypt for millennia, never having left.] “There are no Jews in Egypt,” my little friends would retort. “We never heard of any Jews in Egypt. You can’t be Jewish.”

When I was growing up in 1950s Bensonhurst, in Brooklyn, NY, my identity as a Jew was often called into question. “You mean you’re Jewish? And you don’t know about gefilte fish?” my best friend’s Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish mother asked, shocked to discover that our family ate stuffed grape leaves rather than stuffed cabbage. “What kind of a Jew are you?” schoolmates challenged. When I answered “Sephardic . . . from Egypt,” they would reply. “But all the Jews left Egypt a long time ago, isn’t that what Passover is about?” “No,” I would say, having been taught the words by my father. “Some Jews returned to Egypt when they were expelled from Spain.” [Later I would learn that some Jews actually lived in Egypt for millennia, never having left.] “There are no Jews in Egypt,” my little friends would retort. “We never heard of any Jews in Egypt. You can’t be Jewish.”

Before coming to the U.S., I felt disconnected from feminist theory. I thought this framework labels women as haters of men and seekers of obscure rights. I was not sure who could identify with it or belong to it. For me, it was just a scholarly concept women used to justify their rights. I could not perceive it as an empowering tool, even if it is being so popular. While there is no problem having the concept to be loud and popular, this loud voice did not speak for me. I could not let it represent me or speak on my behalf. Every time I google it, I see angry faces, naked women, people yelling, women in chains, and much more. Instead of accepting it, I resisted it.

Before coming to the U.S., I felt disconnected from feminist theory. I thought this framework labels women as haters of men and seekers of obscure rights. I was not sure who could identify with it or belong to it. For me, it was just a scholarly concept women used to justify their rights. I could not perceive it as an empowering tool, even if it is being so popular. While there is no problem having the concept to be loud and popular, this loud voice did not speak for me. I could not let it represent me or speak on my behalf. Every time I google it, I see angry faces, naked women, people yelling, women in chains, and much more. Instead of accepting it, I resisted it.