Part 1 was posted yesterday.

That richness of self may be what May chased her entire life: for herself to be enough. Eight years later in Journal of a Solitude, May further explores her relationship with solitude:

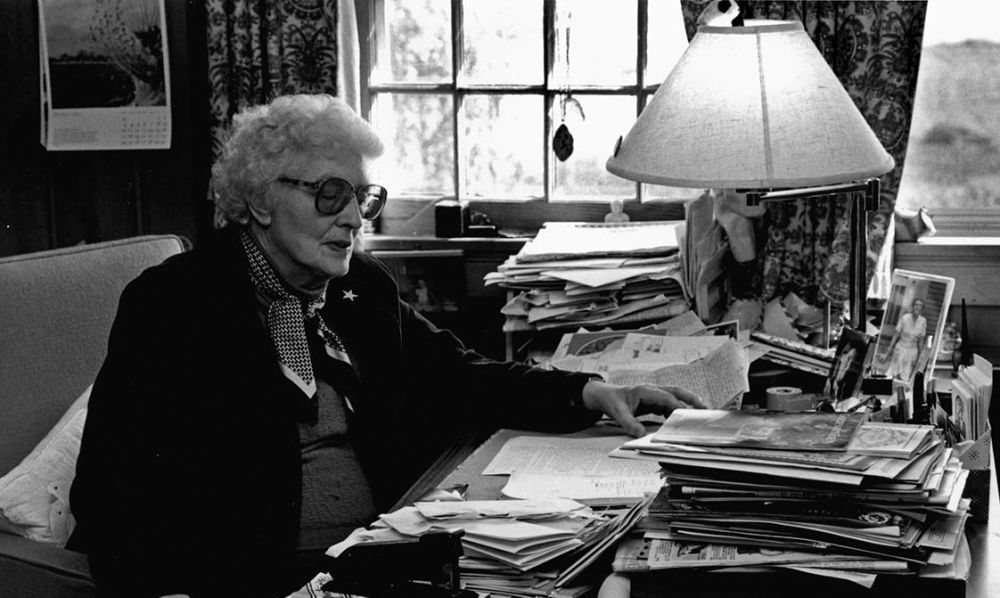

May’s house in Nelson, NH

“Later on in the night I reached quite a different level of being. I was thinking about solitude, its supreme value. Here in Nelson I have been close to suicide more than once, and more than once have been close to a mystical experience of unity with the universe. The two states resemble each other: one has no wall, one is absolutely naked and diminished to essence. Then death would be the rejection of life because we cannot let go what we wish so hard to keep, but have to let go if we are to continue to grow”(57).

But May knew the drill, and wrote such to a friend, “I came to see that my loneliness (acute and awful) was really a loneliness for myself”(Peters 279).

In Journal of a Solitude, May reveals the challenges surrounding the writing of Mrs. Stevens in 1965, the guts it took, the mission she had in mind:

“On the surface my work has not looked radical, but perhaps it will be seen eventually that in a “nice, quiet, noisy way” I have been trying to say radical things gently so that they may penetrate without shock. The fear of homosexuality is so great that it took courage to write Mrs. Stevens, to write a novel about a woman homosexual who is not a sex maniac, a drunkard, a drug-taker, or in any way repulsive; to portray a homosexual who is neither pitiable nor disgusting, without sentimentality; and to face the truth that such a life is rarely happy, a life where art must become the primary motivation, for love is never going to fulfill in the usual sense.

“But I am well aware that I probably could not have “leveled” as I did in that book had I had any family (my parents were dead when I wrote it), and perhaps not if I had had a regular job. I have a great responsibility because I can afford to be honest. The danger is that if you are placed in a sexual context people will read your work from a distorting angle of vision. I did not write Mrs. Stevens until I had written several novels concerned with marriage and family life”(91).

The need to mask in life and art, the patience to slowly roll out the truth, in a “nice, quiet, noisy way.”

Margot Peters weighs in on Mrs. Stevens in May’s biography:

“While Hilary Stevens might outrage those who believe that women artists are not deviants, her claim that women must find their own language and subjects in the dominant world of men’s literature was a radical concept in 1965. Mrs. Stevens’s idea of “woman’s work” also goes far to explain the puzzle of May Sarton’s own oeuvre: how such an aggressive, volatile, and violent person could produce novels and poems that ultimately transcend conflict. Like Hilary Stevens, May believed that her creative demon was masculine, her sensibility feminine”(254).

”Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing was a novel before its time. In coming years, as the gathering momentum of the feminist, gay, and civil rights movements raised America’s consciousness and women’s studies departments sprang up on campuses across the nation, Mrs. Stevens brought its author a fame she had sought all her life”(259).

While living in Nelson, May received letter upon letter from women envying her seemingly ideal situation, but May wanted to set the record straight, that her living alone in a small rural town in New Hampshire was not the panacea so many imagined.

“No partner in a love relationship (whether homosexual or heterosexual) should feel that he has to give up an essential part of himself to make it viable. But the fact is that men still do rather consistently undervalue or devalue women’s powers as serious contributors to civilization except as homemakers. And women, no doubt, equally devalue their own powers. But there is something wrong when solitude such as mine can be “envied” by a happily married woman with children.

“Mine is not, I feel sure, the best human solution. Nor have I ever thought it was. In my case it has perhaps made possible the creation of some works of art, but certainly it has done so at a high price in emotional maturity and in happiness. What I have is space around me and time around me. How they can be achieved in marriage is the real question. It is not an easy one to answer”(Journal 123).

Make no mistake, although May was living alone, she was not alone. She had frequent visitors and was often off lecturing, leading workshops and teaching seminars. Nelson was an attempt to extract, one met with mixed results.

May Sarton grappled with life’s intangibles while living as close as possible to tangible pleasures; she struggled with darkness in the greatest sense and basked in full-on light in the intimate moments, where she found peace. Nothing was meaningless; everything was meaningless. She bared her soul and her heart, revealed her gifts and vulnerabilities in a way not many dare.

“Rage is the deprived infant in me but there is also a compassionate mother in me and she will come back with her healing powers in time”(Peters 339). How accurately May’s sums herself up here; for all her crossness and fire, she was generous to a fault, gifting thousands of dollars to friends every single year.

May became a gardener, as was her mother. In Nelson, she planted, weeded, harvested and displayed vibrant, oh-so-necessary flowers. It became a true labor of love, for even if she wasn’t up to doing such work, she forced herself out of doors to commune with the rocky soil, the scent of dirt and plants, the distinct hope of growth and blossoms. This seemed the antidote to starving for love and light:

“For a long time, for years, I have carried in my mind the excruciating image of plants, bulbs, in a cellar, trying to grow without light, putting out white shoots that will inevitably wither. It is time I examined this image. Until now it has simply made me wince and turn away, bury it, as really too terrible to contemplate.”(Journal 57).

May lamented in a letter to a friend,

“My rage and woe come from great and prolonged suffering that the critics have never never given the poems a break. I see the mediocre winning and I suppose to keep going I have to get mad…better than committing suicide. It is a fight to survive somehow against the current. I am a salmon leaping the waterfalls”(Peters 279).

Thank you for passionately and patiently swimming against the current, May.

May Sarton is a #NastyWomanWriter.

(Here’s the post about May’s resting place in the Nelson cemetery: The Phoenix Takes Its Rest: Visiting May Sarton’s Grave.)

©Maria Dintino 2019

Works Cited:

Peters, Margot. May Sarton: a Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Sarton, May. Journal of a Solitude. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1973.

Sarton, May. Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1965.