This was originally posted on 1/30/12 and then again on 1/29/24. Moderator’s Note: We are posting Carol’s legacy post on Sunday this week rather than Monday because today is the Feast Day of St. Brigid. We also feel this is an important message in these difficult times.

May we remember Brigid on her day in the fullness of her connection to bountiful and life-giving earth by setting a bowl of milk on an altar or special place in the garden on her holy day. Who knows, a snake just might come to drink from it.

The Christian Feast Day of St. Brigid of Kildare, one of the two patron saints of Ireland, is held on February 1, the pre-Christian holiday known as Imbloc. It is well known that St. Brigid has the same name as a pre-Christian Goddess of Ireland, variously known as Brighid (pronounced “Breed”), Brigid, Brigit, Bride, or Bridie. The name Brigid is from the Celtic “Brig” meaning “High One” or “Exalted One.” Brigid like other Irish Goddesses was originally associated with a Mountain Mother, protectress of the people who lived within sight of her and of the flocks nurtured on her slopes.

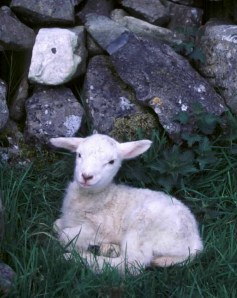

Imbolc marked the day that cows and ewes give birth and begin to produce milk. It was also said to be the day when hibernating snakes (like groundhogs) first come out of their holes. In northern countries, Imbolc signals the beginning of the ending of winter. The days have begun to lengthen perceptibly after the winter solstice when the sun stands still and it seems that winter will never end. At Imbloc spring is not yet in full blossom. But if hibernating snakes come out of their holes, it is a sure sign that the processes of transformation will continue and warmer days will not be far off. As Marija Gimbutas says, “The awakening of the snakes meant the awakening of all of nature, the beginning of the life of the new year.”

St. Brigid’s male counterpart, St. Patrick, was said to have driven all of the snakes out of Ireland. This legend reiterates the Biblical association of snakes with evil and temptation. In Old Europe snakes were symbols of life and regeneration. Moreover, snakes eat mice and rats, protecting granaries and helping to create hygiene and therefore heath in the home. In driving snakes out of Ireland, St. Patrick, like his precursors Marduk, Apollo, and St. George was re-enacting the myth of slaying of the Goddess. St. Patrick may not have driven all of the snakes out of Ireland, but Christianity succeeded in making fear and hatred of snakes nearly universal in Christian cultures. Yet in the Lithuania of Marija Gimbutas’ youth protective snakes were encouraged to live underneath houses and were fed with bowls of milk. Could it be that snakes were lured out of their holes at Imbloc by setting out of bowls of the first milk produced by the lactating ewes and cows?

For agricultural peoples, the day that cows and ewes give birth is not simply another marker of the coming of spring. When human beings domesticated cattle and sheep by providing them with food, care, and shelter, we began to depend upon these animals for milk, cheese, butter, yogurt, meat, leather, and wool. In domesticated herds and flocks, most of the animals are female because the females give birth and produce milk. A few of the males will be allowed to survive, but most will be eaten on feast days and at celebrations of birth and marriage. Agricultural peoples knew that males were needed to impregnate the females, but in celebrating the day that ewes and cows give birth and begin to produce milk, our Old European ancestors were affirming female power to give birth and nurture life. For them, Imbloc was a reminder that the lives of human beings and animals are intertwined in the processes of birth, death, and regeneration in the web of life, which they understood to be the cycles of the body of the Goddess.

“Human alienation from the vital roots of earthly life” may be part of our heritage, but as Marija Gimbutas tells us, “the cycles never stop turning, and now we find the Goddess reemerging from the forests and mountains, bringing us hope for the future, returning us to our most ancient human roots.” Brigid’s day is a good time to think about our connections to milk-giving cows and ewes, and to pledge ourselves to do what we can to end the torture chambers of factory farming, based on the misguided assumption, spawned of patriarchy, capitalism, and modern science, that animals have no feelings and no right to frolic and give birth on the mountainsides of the Mother. And let us not forget the snakes who have been living on Mother Earth far longer than humans and whose movements became the patterns for folk dances and symbols of the dance of life the world around.

(Originally presented in somewhat different form at the Feast of St. Brigid at Christ Church Cathedral in Houston in 2004.)

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I would like to say, you’re misspelling Imbolc.

Here is the correction.

Imbolc is the standard and most common spelling for the Gaelic festival held on February 1st, marking the beginning of spring. While occasionally spelled Imbolg (reflecting Old Irish roots), “Imbolc” is the generally accepted form. It is sometimes also referred to as St. Brigid’s Day or Candlemas.

While I appreciate this post, the consistent misspelling of the day is disconcerting.

LikeLike

Thank you Patty for the head’s up on that one. While we don’t usually “police” the varieties of spellings, in this case it is a clear mistype. I have corrected this post as well as the original.

LikeLike

Thanks. I do not usually edit in public but I see this misnamed a lot.

LikeLike

I wanted to share an experience I had while walking with a tour group on the cliffs above Bride’s Bay in Wales. We had seen St Davids (patron St. of Wales) and were on our way to see the ruins of his small stone cell (David was one who believed in suffering…cold water plunges) but there was also a holy well there, below the small chapel for St. Non, the mother of David. It was thought she had been a Druid before being absorbed into the Roman Church. There was a niche across the one lane road that held the image of Virgin Mary and where some old ways practitioners had left corn dolls.

I knew the snake was a symbol of the Goddess Brigid and so I found t fascinating that as we walked the path in the grassy field leading toward the stone ruin, a large black snake crossed in front of us…heading in the direction of St. Non’s and the well. It seemed to validate the power of the Goddess was still alive in Bride’s Bay.

I also see a lot of confusion in posts on Facebook about St. Brigid being the Goddess. But she may also have grown up in the home of a Druid, and she was an abbess who created the Abbey of Kildare and other convents. Pretty unusual for those days. The confusion may arise from her feast day being on the cross-quarter festival that honors the goddess Brigid.

LikeLike

Ah, how satisfying to read this post which I remember well…This Turning is the first of the year and as we move towards more light may we not neglect the giant shadow that has formed hidden by cultural darkness – Stay awake – not just to light but to darkness…. strength comes from acknowledging both..

LikeLike