Viśākhā is often called the greatest female lay follower of the Buddha. She prompted the Buddha to give numerous teachings. She also donated generously to the Sangha (monastic order). Her crowning contribution was building a monastery called Migāramātupāsāda.

Viśākhā is often called the greatest female lay follower of the Buddha. She prompted the Buddha to give numerous teachings. She also donated generously to the Sangha (monastic order). Her crowning contribution was building a monastery called Migāramātupāsāda.

She is said to either die as a “stream-enterer” (a person who will definitely become enlightened, no matter how many life times it will take). Another account about her afterlife says that she would live for eons in happiness in one of the divine realms before achieving the final Liberation there and then.

Viśākhā appears in numerous Suttas of Theravadin Canon. From the modern feminist point of view, the content of these discourses reinforces patriarchal gender stereotypes. In particular, Viśākhā is portrayed as a caring Mother for her relatives, Bhikkhus (Buddhist monks and nuns), and other people.

Continue reading “Viśākhā: Surrogate Mother of Buddhism by Oxana Poberejnaia”

There is a Sutta in Theravadin Canon called “

There is a Sutta in Theravadin Canon called “ It would not matter if a head of a patriarchal organisation is a feminist or not. She or he will play a role of a head of a patriarchal system. That is, unless she changes the system altogether and it ceases to be patriarchal.

It would not matter if a head of a patriarchal organisation is a feminist or not. She or he will play a role of a head of a patriarchal system. That is, unless she changes the system altogether and it ceases to be patriarchal. When my students read about the Buddhist concepts of non-resistance, non-attachment, and living in the present, one of the first protests I end up addressing is how these ideas seem to negate progress, goal-setting, or success. What my students don’t yet see is how clinging to a particular end can hinder creativity and the pleasure of the journey to a degree that sometimes compromises success.

When my students read about the Buddhist concepts of non-resistance, non-attachment, and living in the present, one of the first protests I end up addressing is how these ideas seem to negate progress, goal-setting, or success. What my students don’t yet see is how clinging to a particular end can hinder creativity and the pleasure of the journey to a degree that sometimes compromises success. Separatism and dualism do not usually serve me. I understand that denying unity and reducing the multi-prismatic complexity of existence muddies up our vision of reality and can sometimes clog up the channels to compassion. So knowing that this perspective is not universal, but temporarily (at least) healing to me, a particular body with a life situation that gives me access to this kind of thinking, I explore taking a maternal perspective toward my body.

Separatism and dualism do not usually serve me. I understand that denying unity and reducing the multi-prismatic complexity of existence muddies up our vision of reality and can sometimes clog up the channels to compassion. So knowing that this perspective is not universal, but temporarily (at least) healing to me, a particular body with a life situation that gives me access to this kind of thinking, I explore taking a maternal perspective toward my body. In the winter of 2013, I went on pilgrimage to Kathmandu, Nepal. While there, I visited the Khachoe Ghakyil Ling (Pure Land of Bliss) Tibetan Buddhist nunnery, the largest in Nepal with about 400 nuns. It’s affiliated with the nearby Kopan monastery where I stayed in the retreat housing. The nuns gave a group of us a tour of the gompa (meditation room), classrooms, workshops, and kitchen. The studies at the nunnery include math, science, and English, Nepali, and Tibetan languages, as well as meditation, debate, ritual arts, and chanting, the same education that the monks receive at the monastery. When not engaged in prayer and education, the nuns produce herbal incense renowned for its healing properties, which clear and uplift the mind. Not surprisingly for their ambitious program, a nun’s average day is 14 hours long.

In the winter of 2013, I went on pilgrimage to Kathmandu, Nepal. While there, I visited the Khachoe Ghakyil Ling (Pure Land of Bliss) Tibetan Buddhist nunnery, the largest in Nepal with about 400 nuns. It’s affiliated with the nearby Kopan monastery where I stayed in the retreat housing. The nuns gave a group of us a tour of the gompa (meditation room), classrooms, workshops, and kitchen. The studies at the nunnery include math, science, and English, Nepali, and Tibetan languages, as well as meditation, debate, ritual arts, and chanting, the same education that the monks receive at the monastery. When not engaged in prayer and education, the nuns produce herbal incense renowned for its healing properties, which clear and uplift the mind. Not surprisingly for their ambitious program, a nun’s average day is 14 hours long. Since I am averse to crowds and rebellious by nature, I ducked out of much of the sight-seeing and instead spent my time engaging with the novitiates, the young nuns who were milling about before dinner because they had completed their classes, daytime prayers, and other duties. We asked each other questions like “What’s your name?” and “Where are you from?” Then I was treated to “Watch me do this!” and “Can you do this?” because the language of children is universal. Yet, what was special about these girls was that they were being given food, shelter, and an education — opportunities that many their ages, especially girls, would never know.

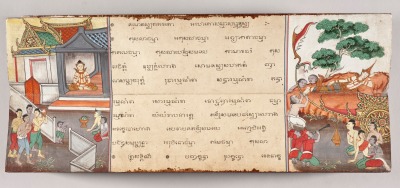

Since I am averse to crowds and rebellious by nature, I ducked out of much of the sight-seeing and instead spent my time engaging with the novitiates, the young nuns who were milling about before dinner because they had completed their classes, daytime prayers, and other duties. We asked each other questions like “What’s your name?” and “Where are you from?” Then I was treated to “Watch me do this!” and “Can you do this?” because the language of children is universal. Yet, what was special about these girls was that they were being given food, shelter, and an education — opportunities that many their ages, especially girls, would never know.  One of the most popular texts in Thai Buddhism (which is of Theravada tradition) is called

One of the most popular texts in Thai Buddhism (which is of Theravada tradition) is called