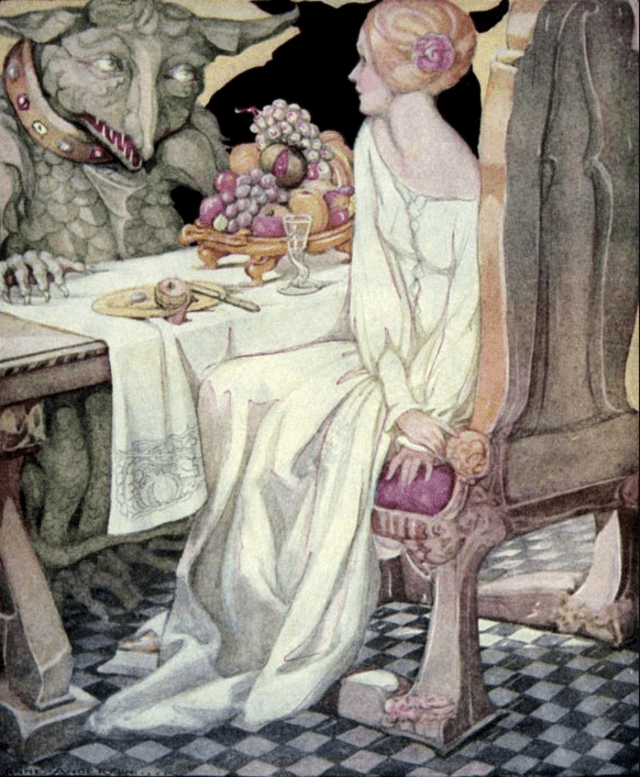

For most of cinematic history, the moral universe of film was anchored in clarity. The hero was dharmic—principled, disciplined, and guided by a moral compass that was neither ambiguous nor negotiable. The villain, by contrast, represented a clear rupture in the ethical order. Actions had consequences; justice was intelligible; human beings possessed agency, responsibility, and accountability. Main stream cinema reflected a world in which right and wrong, virtue and vice, were not merely narrative devices but metaphysical coordinates. One could locate a character on the map of moral compass with precision.

Older Indian cinema often adhered to a strong moral framework in which even the most charismatic or beloved protagonists were ultimately required to pay for their transgressions on screen. Unlike today’s era of morally ambiguous films—where anti-heroes may triumph, consequences are negotiable, and ethical lines are intentionally blurred—classic cinema rarely allowed wrongdoing to go unpunished. Yet this does not mean that earlier films lacked sophistication or ambiguity; rather, they explored moral conflict within a clear ethical horizon, allowing audiences to empathize deeply with flawed characters while still witnessing their inevitable downfall. For example, in Deewaar (1975), Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay becomes an iconic rebel whom audiences passionately sympathize with, yet he must die in the end to restore moral order. In Parwana (1971), his obsessive, morally dark character meets a tragic ending, demonstrating the same principle. Even beyond Bachchan, iconic villains like Gabbar Singh in Sholay (1975) was originally written to die as a narrative necessity. Through such storytelling, older cinema balanced empathy with accountability, illustrating that complexity and moral clarity once powerfully coexisted.

Continue reading “Evolution of Cinema and Shift of the Moral Universe by Sabahat Fida”