This was originally posted on June 15, 2012

I am less concerned with the legitimacy or morality of public breast-feeding . . . rather I am asking what contributes to this strange binary of, on the one hand, social acceptability of near-porn-like images of breast used in advertising, i.e. Victoria Secret, while on the other hand, internal conflicts some feel when viewing a baby/child feeding at the breast?

Beyond the “war on women” initiated by the Republican party on women’s reproductive rights, the issue of women’s breast, or more specifically, the nursing breast, has been making itself know in the media. The recent Time magazine cover of Jamie Lynne Grumet breast-feeding her three-year-old son produced a flood of controversy centering on “attachment parenting,” which promotes, among other things, breast-feeding beyond infancy. Parent magazine recently profiled two military mothers breastfeeding in public while in uniform. For some, this perceived breach in social decorum is akin to urinating and defecating openly while wearing your uniform. Responding to the outcry, Air Force spokesperson Captain Rose Richeson states, “Airmen (sic) should be mindful of their dress and appearance and present a professional image at all times while in uniform.” In other words, it is suggested nursing military mothers pump and bottle-feed their babies when wearing their uniform in public spaces. And finally, Hadley Barrows of Minnesota was asked to leave the library by a security guard because her nursing in public was a form of “indecent exposure.” In this post I am less concerned with the legitimacy or morality of public nursing (although I have no issue with it), instead I am asking what contributes to this strange binary of, on the one hand, social acceptability of near-porn-like images of breast used in advertising, i.e. Victoria Secret, while on the other hand, internal conflicts some feel when viewing a baby/child feeding at the breast? Drawing from the work of Margaret Miles and her text, A Complex Delight: The Secularization of the Breast, 1350-1750, social attitudes and the public display of women’s breast can best be understood when the breast is viewed as a coded symbol that informs, through artistic representation, complex patterns of discourse.

Continue reading “Archives from the FAR Founders: The Tale of Two Breast: From Religious Symbol to Secular Object by Cynthia Garrity Bond”

A week ago today was my birthday. I’m the same age as my mother when she died of a stroke some twenty-eight years ago. This past year has been marked by the deaths of close friends and family; most recently my Uncle Jack who almost made it to his 93rd birthday. This latest passing, coupled with being the same age as my mother when she passed, has left me more than a bit reflective of life and vulnerability. This internal examination has lead me to acknowledge another loss I have been ignoring for a few years—my love affair with the divine.

A week ago today was my birthday. I’m the same age as my mother when she died of a stroke some twenty-eight years ago. This past year has been marked by the deaths of close friends and family; most recently my Uncle Jack who almost made it to his 93rd birthday. This latest passing, coupled with being the same age as my mother when she passed, has left me more than a bit reflective of life and vulnerability. This internal examination has lead me to acknowledge another loss I have been ignoring for a few years—my love affair with the divine. As many of you may already know, on August 24, 2016, feminist theologian and scholar Rosemary Radford Ruether suffered a significant stroke. There has been some speculation from those who know or have known Rosemary about her current condition. Here is the short of it. While Rosemary has made progress, her doctors and therefore Medicare feel it is insufficient to warrant continued physical and speech therapies. Those who interact with Rosemary on a daily or weekly basis disagree with this medical prognosis. The stroke damaged the part of Rosemary’s brain that allows for communication, therefore she, at this time, is not able to speak. That said, Rosemary recognizes individuals, is able to respond to some commands and engage in therapeutic exercises. The more attention and care she receives the greater her capacity grows for a more meaningful life that includes a level of agency.

As many of you may already know, on August 24, 2016, feminist theologian and scholar Rosemary Radford Ruether suffered a significant stroke. There has been some speculation from those who know or have known Rosemary about her current condition. Here is the short of it. While Rosemary has made progress, her doctors and therefore Medicare feel it is insufficient to warrant continued physical and speech therapies. Those who interact with Rosemary on a daily or weekly basis disagree with this medical prognosis. The stroke damaged the part of Rosemary’s brain that allows for communication, therefore she, at this time, is not able to speak. That said, Rosemary recognizes individuals, is able to respond to some commands and engage in therapeutic exercises. The more attention and care she receives the greater her capacity grows for a more meaningful life that includes a level of agency.

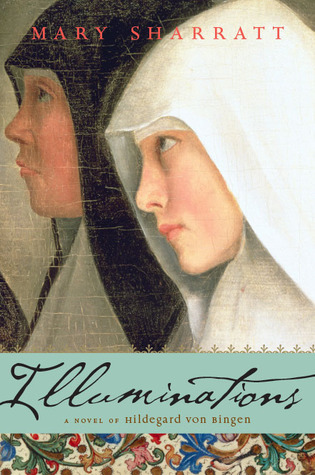

Hildegard, who lived from 1092 to 1179, was the tenth child of a family of minor nobility in the Holy Roman Empire. She’s a sturdy child who loves the outdoors and enjoys running through the forest with her brother. But early in the novel, she learns that she is to be her family’s tithe to the church. Her mother has already arranged for this bright and curious eight-year-old child to be the companion to Jutta von Sponheim, a “holy virgin” who yearns to be bricked up as an anchorite in the Abby of Disibodenberg. Being an anchorite means that, like Julian of Norwich (about 250 years later), this girl and her magistra are bricked in. There is a screened opening in the wall through which their meager meals are passed and through which they can witness mass and speak to Abbott Cuno, the other monks, and visiting pilgrims, but they can never go out. Never. In the Afterword, Sharratt writes that “Disibodenberg Abbey is now in ruins and it’s impossible to precisely pinpoint where the anchorage was, but the suggested location is two suffocatingly narrow rooms and a narrow courtyard built on to the back of the church” (p. 272). As Sharratt vividly shows us, Hildegard survived in that awful place for thirty years.

Hildegard, who lived from 1092 to 1179, was the tenth child of a family of minor nobility in the Holy Roman Empire. She’s a sturdy child who loves the outdoors and enjoys running through the forest with her brother. But early in the novel, she learns that she is to be her family’s tithe to the church. Her mother has already arranged for this bright and curious eight-year-old child to be the companion to Jutta von Sponheim, a “holy virgin” who yearns to be bricked up as an anchorite in the Abby of Disibodenberg. Being an anchorite means that, like Julian of Norwich (about 250 years later), this girl and her magistra are bricked in. There is a screened opening in the wall through which their meager meals are passed and through which they can witness mass and speak to Abbott Cuno, the other monks, and visiting pilgrims, but they can never go out. Never. In the Afterword, Sharratt writes that “Disibodenberg Abbey is now in ruins and it’s impossible to precisely pinpoint where the anchorage was, but the suggested location is two suffocatingly narrow rooms and a narrow courtyard built on to the back of the church” (p. 272). As Sharratt vividly shows us, Hildegard survived in that awful place for thirty years.