Talking of decoloniality in religion and theology is today a fashionable stance that has been adopted even by the academic and political mainstream. As Latin Americans, decolonial perspectives affect us firsthandedly. For the last 500 years, our continent has nurtured resistance struggles against the racial, sexual, economic, ethnic and religious violences that emerge from the numerous process of colonization we have endured. With this in mind, in this article we contribute to the debate on decolonization of our religious phenomena.

Decolonizing is to Assume that all Religion can Operate as a Colonizing Agent

The expansion of European colonialism in Latin America transpired through all aspects of social existence and gave rise to new social and geocultural identifications (e.g. “European”, “American”, “Indian”, “African”, etc). The consequences of this domination reverberate to this day.

In this regard, we should not loose track of the fact that all abrahamic religions had their genesis within Latin America in the form of colonial presence. In other words, most of our religious expressions are the product of colonial forms of governance, which benefited from an exclusionary instrumentalization of the religious narratives as a tool to ‘dignify’ and ‘enhance’ the population as ‘colonial subjects’.

This was the case of Christianity. The mission carried out by the first European conquistadores in the Americas was characterized by the drawing of exclusionary theological lines that legitimized some, questioned others, and condemned many. Colonization thus manifested itself in part through spiritual violence on native populations. Evangelization, in this regard, was biopolitical in nature; it entailed the pushing of non-European bodies (and souls) into ‘Otherness’.

This illuminates unto why, for example, nowadays interfaith relations have become a problem, rather than a resource for many Latin American Christian congregations. It is often assumed that to establish lasting links of solidarity with religious ‘Others’ puts at risk the core elements which have been taught to enhance our population by the different metropoles that have governed and preached in our midst.

It is well established that for too long the bases of Christianity in the Americas were built upon imposed and/or conditioned conversions which constantly demanded and reminded people that in order to have ‘goodness’ reside in them, they had to be someone essentially different to who they were; they had to be Christian (Rivera Pagán 2013, 2014; Silva Gotay 1998, 2005). In this regard, long established religions such as Judaism, Islam, Spiritism, and Afro-Atlantic religions such as Santería or Palo have been relegated to inferior statuses in some still colonial contexts, such as Puerto Rico (Caraballo-Resto 2016; Román 2007).

A similar case, can be found within Islam. As mentioned in a previous article, many Muslim congregations in the Americas have done well in mirroring the colonial practices of Christianity. Despite common assumptions, some contemporary Muslim groups have come to our lands with the clear aim of Arabization and, again, through spiritual violence they categorize locals as “others” and, thus “subordinate” them as perpetual ‘underage believers’, who seem to need the Arab tutorial aid relentlessly. At times, their theologies are reminiscent of those expressed by Catholicism 500 years ago: A call to abandon local trajectories and spiritualities, in favor of adopting Middle Eastern names, language, arts and aesthetics, social manners, political causes and even diet. Only then, are us Latin American to be considered by some of these communities as “Noble Savages”.

Although some scholars linked to decolonial studies within Islam have difficulty accepting this, Islam has historically been instrumentalized as a colonizing agent in the Middle East, West Africa, Asia and the Indian Subcontinent.

If we talk about Islam and decoloniality in the same sentence, there should be honesty on these facts.

Colonization occurs not only through the sword and war, also through trade, culture and social discourses that become hegemonic and religion. In this regard, the ‘jihad of the soul’ is seldom devoid of politics. The absence of blood is not tantamount to a lessening of colonial violence. There are many and different ways to curtail, cancel and oppress a people without resorting to their physical extermination.

Religion and the Heterosexual Regime

Colonial religions in Latin America have been characterized by an hegemonic discourse based on heterosexuality as a compulsory scheme, androcentrism, ableism and speciesism. Historically, this has entailed the exercise of a new religious taxonomy (eg. ‘Moro’, ‘Marranos’, ‘noble souls’, etc.). Yet, this also corresponded to an encompassing system of power that intersected all control of collective authority, labor, racial relations, the production of knowledge, as well as sexual access and meaning.

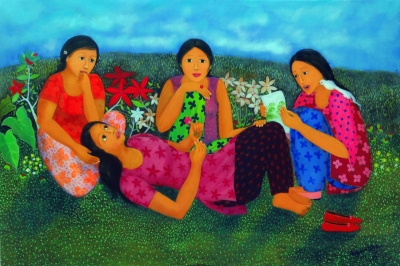

It is well known that many indigenous peoples of the Americas were matriarchal, recognized more than two genders, recognized homosexuality and “third” gendering positively and understood gender in much more problematized terms rather than in the binary terms of subordination monotheistic system imposed.

Such dichotomy not only found its way in Latin America. It also transpired in parts of Africa, which were later linked to our Latin-American contexts by way of slavery. This has been dealt at lengths by Nigerian feminist scholar Oyéronké Oyewùmí, in her work The Invention of Women (1997). In it she states that gender was not an organizing principle in Yoruba society prior to European colonization (idem: 31). Instead, she argues that gender has “become important in Yoruba studies not as an artifact of Yoruba life but because Yoruba life, past and present, has been translated into English to fit the Western pattern of body-reasoning” (idem: 30).

So, it becomes all the more important to consider the changes that religious colonizers have brought, as well as the lip service we’ve paid to it, in order to understand the scope of our Latin American organizations of sex and gender under colonialism.

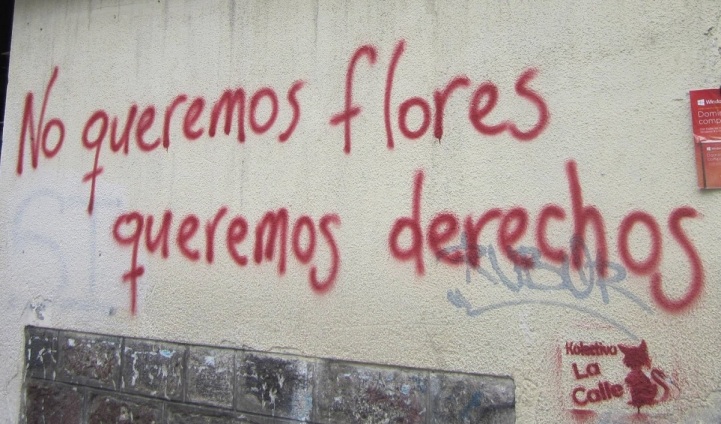

Theology of Dissent in Response to Religious Heteropatriarchy

A decolonial theology must be one of dissidence if it is to have any liberating character. ‘Dissidence’, here, is not used as a mere label of disagreement, but rather as a situational stance from which the very bases of our legitimization as colonial subjects are constantly contested. And just as the expansion of religious colonialism in Latin America transpired through all aspects of social existence and gave rise to new social and geocultural identifications, a decolonial theology of dissidence must do the same—starting from our own gendered bodies.

In sexual terms, Latin American women and non-heterosexual people have been historically defined in relation to heterosexual men as the norm. In other words, women are those who do not have a penis, and non-heterosexual men are those who do not use their penis according to the norm (Lugones 2003). From a decolonial theology of dissidence this must be contested—placed in a situation of uncomfortable political transactions perennially.

From this point of view, a decolonial theology of dissent is much more than a body of intellectual writings. It is a daily practice—a quotidian mode of resistance—that involves people at the grassroots where the challenges of exclusion are negotiated. Yet, something is to be said for the epistemological zones of privilege where colonialism is also instantiated. There is no decoloniality without resistance, and there can be no resistance against the traditional hegemonic enclaves where colonialism is legitimized, as long as the centers where knowledge is produced conceive people in resistance as “objects of study”, rather than “fellows in knowledge-building”.

Up to this day, ‘Otherness’ is one of the most deeply rooted archaeological legacies left by our colonial religiosities. Upon its finding, some people of faith in Latin America are now left to determine how best to deal with religion(s) in an inclusive, liberating and welcoming way, so that our social contexts become ones where religious, gendered, ethnic, linguistic, racial, and able diversities are not thought of as problems, but a resources to strengthen ties. Only then can we help truly shift this time of instability for our region.

Decolonizing religion in Latin America entails understanding that the religious question is always political, and as such must be contested. If there is any liberating potential in the religious phenomena, this is due to a lucid dissidence that eludes colonial privilege and embraces an ethical compromise beyond religious labels.

Vanessa Rivera de la Fuente is a social communicator, writer, mentor in digital activism and community educator in gender and capacity development. She has led initiatives for grass roots female leaders’s empowerment in Latin America and Africa. She is an intersectional latin muslim feminist in the crossroads between Religion, Power and Sexuality. Her academic work addresses Feminist Hermeneutics in Islam, Muslim Women Representations, Queer Identities and Movement Building. Vanessa is the founder of Mezquita de Mujeres (A Mosque for Women), a social media and educational project based in ICT that aims to explore the links between feminism, knowledge and activism and highlights the voices and perspectives of women from the global south as change makers in their communities.

Juan F. Caraballo Resto is professor of Sociology and Anthropology of University of Puerto Rico Reinto Cayey. PhD in Social Anthropology from University of Aberdeen, Scotland.

Featured Image: Indigenous woman in Chiapas, Mexico, part of the Islamic mission of Dawa in the area, wearing a hiyab and showing a Qur’an in Spanish,

Vanessa Rivera de la Fuente

Vanessa Rivera de la Fuente