Demeter and Persephone, Hera, Athena, Medusa, Artemis are often the first, sometimes only, goddesses modern women experience, and they have profoundly influenced our 21st century attitudes about gender, violence, and more. Yet, as Max Dashu says in her new book, Women in Greek Mythography, Greek history has “served as a template for supremacy, from male domination and Hellenic colonization, to modern Eurocentric ideologies about history” (xi). While most Greek scholarship generally glosses over these malevolent influences and ignores women’s lives, Dashu focuses on “female spheres of power, priestesses, witches, and of course systemic patriarchy” (xi) in order to “map realities of women’s lives, both their spiritual authority and their subjugation; the spaces they carved out, their ceremonies, and the stories they wove into their tapestries” (xi).

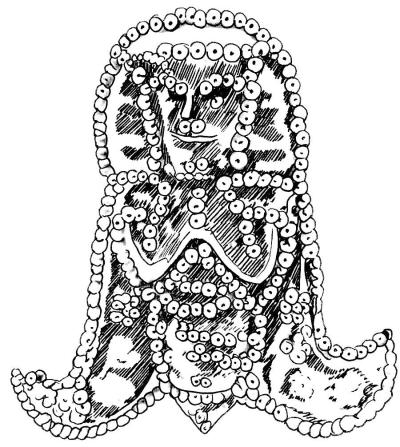

Women in Greek Mythography is not only a fascinating historical story of Greek myth and religion to be read cover-to-cover, but a rich sourcebook full of meticulously documented facts. She draws from scholarly works of history and mythography, as well as analyzing images on vases, friezes, sculpture and more. She has carefully rendered 270 drawings of these images so that readers can judge their meaning themselves. She delves into language, seeking out the origins of words that may indicate where goddesses and myths originated and their relationships to one another. She demonstrates that goddess mythologies often had many variations, sometimes conflicting, with many “countless regional deities that were subsumed under Olympian names, the local origin myths, ceremonies, and customs” (xiv).

Let’s follow some of the book’s major themes. Creation myths of the Titan goddesses, or titanides, who were the goddesses before the more familiar Olympians, offer beauty, mystery, and a celebration of female divinity, strength, and wisdom. As Dashu says, “These beings are not personalities but powers of Nature, realms of existence” (3). Nyx, or Night, Gē, or Gaia, Tethys, Thetis, and Eurynome each have their own unique stories of how the universe came into being that are profoundly moving and affirming of female creative power.

Other titanides are essential to the cosmic order, including Themis, the goddess of divine law, the Horai or “the Seasons, Hours, and All the Cycles of Time” (31), and the Moirai or the Fates, who become the Furies in the face of injustice. Mnemosyne is the goddess of memory or remembrance, Nemesis “represents the inexorable justice of divine Law toward all who violate the Order of Nature while Hekate, “determines success or failure in human affairs, and her aid is invoked in most areas of life” (52).

About 2000 BCE, Indo-Europeans invaded Greece and began to impose their warlike, patriarchal culture on earlier Aegean peoples. Stories like the Iliad and the Odyssey and new myths featuring Olympian gods or revised ancient Titan myths began to feature horrendous violence against women, including abduction, rape, enslavement, and murder. The Trojan War begins with the sacrifice of a young woman so the Greeks can sail to Troy and the murder of a woman captive. Zeus rapes his daughter, Persephone, his sister Demeter, and his mother. Numerous women are captured in war and are raped, captured, and enslaved. While glossed over in the tales and myths, these stories are depicted in detail in art and everyday objects.

Dashu details how the myths of even once highly revered ancient goddesses began to be rewritten, especially that of Hera and Athena. Hera, once sovereign, independent and unmarried, is “locked into marriage and is turned into the ultimate patriarchal wife” (134), turning her jealous anger towards and punishing “her husband’s victims and paramours” (134). “Athena became the ‘patron deity of the state’ (and not only of Athens). She protected male heroes, warriors, invaders, and colonizers.” (180). Dashu also gives a convincing argument of the connection between violence against women and colonization by the Greeks. Not only were these conquests often symbolized in myths of rape of maidens, but rape was used in real life as a method of terrorizing the population into submission.

Even as the myths of the Greek goddesses echoed the increasing and violent subjugation of women, some women, especially elites, still maintained their sphere of spiritual power. Dashu documents that for 1500 years, rulers and others from all over Greece and elsewhere consulted the oracle at Delphi, always a woman, on their most momentous decisions. Eventually, however, Delphi, as well as other places where women gave prophecies, were dedicated to male gods. For millennia, women were also honored as snake and bee priestesses in various places, conducting ceremonies like the women’s Mysteries at Eleusis.

You are invited to watch a video about Women in Greek Mythography, featuring music, by permission, by Layne Redmond,

Dashu, an independent scholar, founded the Suppressed Histories Archives in 1970 for the purpose of, according to her website, http://www.suppressedhistories.net, “Restoring Women to Cultural Memory.” She has created 150 presentations as well as “articles, photo essays, books, and videos fleshing out the cultural heritages that have been hidden from us.” Videos are available at https://www.youtube.com/@maxdashu/videos. Readers can also subscribe to her annual ongoing course at https://suppressed-histories.teachable.com/courses.

Women in Greek Mythography is the second book to be published in her series The Secret History of the Witches which will eventually include sixteen volumes. The first book, Witches and Pagans, was published in 2016. You can find more information on the series as well as excerpts at https://www.suppressedhistories.net/secrethistory/secrethistory.html.

Dashu’s books provide the larger context of women’s spiritual sphere of power over millennia as well as current scholarship with an acknowledgement that more is being learned every day. Dashu’s work shines a light on where we, as women across the globe and the millennia, have been and offers hope of a future where women are powerful and celebrated, which is vital to a peaceful, just, sustainable world. Women in Greek Mythography is an essential resource for anyone wishing to understand the complexity and sometimes profound beauty as well as misogynistic horror of the Greek myths, and their meaning for the women of ancient Greece and of the 21st century.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Women in Greek Mythography is not only a fascinating historical story of Greek myth and religion to be read cover-to-cover, but a rich sourcebook full of meticulously documented facts.” Great line that reminds me of how depthful this study is. I look forward to reading Max’s book as there is clearly so many layers of knowledge and meaning to glean. So much has been lost and it sounds like this is a book that reclaims much. Thank you for bringing it to FAR.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Janet! Yes – like Max’s other book, Witches and Pagans, I use Women in Greek Mythography all the time as a reference and a resource.

LikeLike

Well…this book is definitely on my book list! Thank you for the review!

As history is being uncovered to include herstory, here are two other books that might interest the readers of FAR. “The Mirror and the Palette–Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: Five Hundred Years of Women’s Self Portraits” by Jennifer Higgie. “Twenty-five Women Who Shaped the Italian Renaissance” by Meredith Ray.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those sound like fascinating books! Thanks, Jan!

LikeLike

You can tell a great deal about a society from examining the myths they hold dear…

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is definitely true! What was especially interesting in the book was to see how the myths changed as the society changed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It makes me wonder how people who follow the Hellenic tradition(s) today resolve it…the nature of the deities they worship vs. how they were portrayed in the myths we have today. How do they know what’s accurate and what isn’t? What was made up by humans trying to prop up their regime vs. what wasn’t?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting questions! I wouldn’t say that I follow Hellenic traditions, but I do find meaning in some Greek myths while realizing that the myth may not be as it was originally. A number of authors like Charlene Spretnak have based rewriting of myths to be as like the original as possible based on what is known of pre-Hellenic culture from archaeology, literature, etc.

LikeLike