The Great Goddess of North Africa and the Near East had many different names. In Canaan, she was Asherah, Mother of Creation, Queen of Heaven, and consort of the male god El/Yahweh. Countless archaeological discoveries of ‘images of the Goddess, some dating back as far as 7000 BC, offer silent testimony to the most ancient worship of the Queen of Heaven’. (Kosnick 2017, Stone 1978)

In Canaan, Asherah’s sacred places included high hills and mountaintops, ‘under every spreading tree and every leafy oak’. Identified with the Tree of Life, Asherah was represented by wooden poles or pillars known as asherim. These were ‘cut and shaped from a tree’, ‘adorned with silver and gold’, and ‘had to be carried’. Her rites were chiefly in the hands of the women, who honoured her with incense and liquid offerings, and baked sweet cakes for the Queen of Heaven.. Women also wove elaborate veils to dress the asherim. (Ezekiel 6:3; Jeremiah 10:3-5, 44:17-18; 7:18-19; 2 Kings 23:7)

Hebrews arrived in Canaan around 1250 BCE, and began a campaign of violence to destroy the existing polytheistic religion (multiple male and female deities, the Goddess predominant) and replace it with their own newly monotheistic paradigm of one male god. The Old Testament reports how Jehovah ‘commanded’ his followers to destroy Asherah and those who worshipped her. People ignored these orders and continued to revere the Queen of Heaven, but in the end – after centuries of brutal violence – Asherah was vanquished, her followers were converted, and her rites were forgotten.

At least, that is the standard narrative. However, traces of Asherah as the life-giving Goddess associated with trees and wooden poles still survive in women’s folk art and ceremonial customs, and the Tree of Life remains a central symbol in textiles, jewellery, and seasonal rituals. (Shannon 2019)

The women of this region have not abandoned their reverence for trees, fertility, milk, rain, and the mysterious divine female figure who combines all these aspects. In southern Morocco, her name is Taghonja.

The Taghonja rain-bringing ritual – also known as Tlghunja, Tlghenja, Talghunja, Tlganja, Aghunja, Aghenja, Taghenja, Tenoghja, Tlaghnja, Taghnunja– is widespread throughout the Maghreb, the Sahel and North Africa. Similar customs are found in Syria, Palestine, Armenia, Greece and Bulgaria. (Abu-Zahra 1988, Shannon 2014)

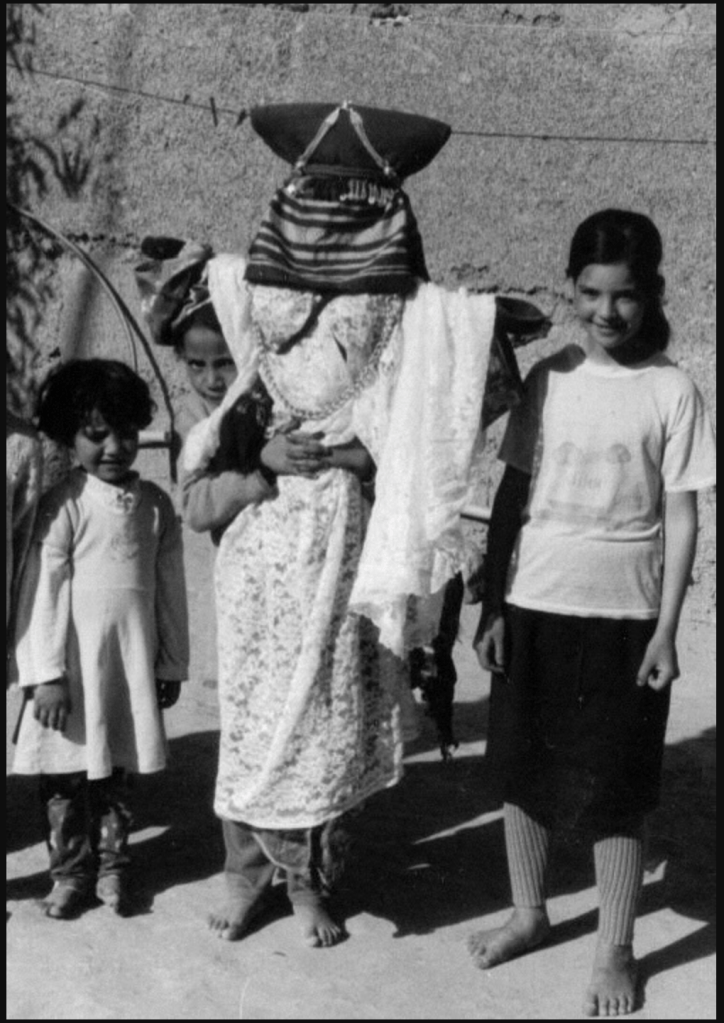

In southern Morocco, when rain is needed, women fashion a female figure from a large wooden ladle or a portable wooden pole such as a broom, winnowing fork, or a reed cane, using smaller wooden ladles for her hands and head. Alternatively (as Westermarck described a century ago), women ‘may also make use of an ordinary piece of wood instead of a ladle and carry this to a neighbouring shrine, where they place it in a standing position and dance and play round it singing.’ (Westermarck 1926)

Taghnunja , Pierre Bergé Museum of Berber Arts, Jardin Majorelle, Marrakech

Both the figure and the ritual are called Taghonja, a Berber (Amazigh) word for ‘ladle’. The ladles which serve as her hands are meant to fill with rain and pour out the flowing water the community so desperately needs. Indeed, the simplest Taghonja ‘dolls’ are made from a single wooden ladle dressed as a bride.

Taghonja is known as the ‘bride of the rain’, reflecting Asherah’s epithets, ‘bride of the sky’ and ‘consort of the storm god’. The women dress her in wedding garments embroidered with silver and gold, and adorn her with fine bridal jewellery and veils. Does this not remind us of the wooden asherim pillars adorned with cloth and dedicated to Asherah thousands of years ago? Does this not echo the description of asherim in the book of Jeremiah, of wooden poles or pillars ‘cut and shaped from a tree’, ‘adorned with silver and gold’ and ‘elaborate veils’, and ‘carried’?

Once the Taghonja is prepared, the women burn incense, pour libations, and offer sweet cakes, just as Asherah’s followers used to do. Accompanied by singing, dancing, clapping, and drumming with frame drums – women’s ways of worship also referenced in the Old Testament – women and children carry the Taghonja to a source of water, sacred tree, threshing ground and other places connected with fertility.

The women sing prayers such as ‘O Tlghunja, O mother of hope, O God give rain’, or ‘Taghenja has loosened her hair, O God mayest thou wet her ear-rings’. (Westermarck 1926) The women, too, might uncover and unbind their hair, which in North Africa (as well as the Balkan and Slavic lands, Anatolia and the Caucasus) is a powerful charm to bring rain. (Barber 2013)

Women and children carry the Taghonja from door to door, dancing and singing, flinging nuts, sweets, and drops of water over the Taghonja, the earth, and one another, laughing as if already enjoying the delight, abundance, and sweetness of the longed-for rain.

Twice I have witnessed this ritual in southern Morocco, and both times, before the ceremony was finished, rain began to fall.

Above all, I remember the women’s laughter, how the Taghonja brought joy and delight to faces lined with worry from years of drought. One of the possible etymologies for the Hebrew name Asherah – aleph-shin-resh – is the same as the root of the word me’ushar, ‘to be blessed’. (Helman 2025) This root is also associated with happiness and laughter. (Moriah 2025)

I can certainly imagine devotees of Asherah in antiquity laughing joyfully as they decorate and celebrate Asherah and her asherim.

According to Miriam Robbins Dexter, another possible Semitic root of Asherah is the Hebrew ʾāšar, ‘to tread, to go straight on.’ (Dexter 2025) In the footsteps of the women, in their procession from water source to threshing ground under gentle raindrops from the sky, carrying their wooden pole dressed as a divine female figure to whom they pray for rain, I see how Asherah too, treads on. Even if hidden from view, her worship was not eradicated after all. It simply went underground, like streams of precious water. This water is there, for those with eyes to see. And it flows straight on.

Excerpted from ‘Asherah and Taghonja’, by Laura Shannon, in the new anthology from Girl God Books, Asherah: Roots of the Mother Tree, edited by Claire Dorey, Janet Rudolph, Pat Daly, and Trista Hendren, with a preface by Miriam Robbins Dexter, Ph.D. Girl God Books, 2025. Order from https://www.thegirlgod.com/asherah.php

For information on Laura’s tours of Women’s Ritual Dances to southern Morocco, please visit laurashannon.net or La Maison Anglaise / Holidays with Heart.

Selected References

Abu-Zahra, Nadia. ‘The Rain Rituals as Rites of Spiritual Passage’. International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 20, No. 4 pp. 507-529. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. The Dancing Goddesses: Folklore, Archaeology, and the Origins of European Dance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013

Dexter, Miriam Robbins. ‘The Great Goddess Asherah’, preface to Asherah: Roots of the Mother Tree. Girl God Books, 2025.

Gélard, Marie-Luce . ‘Une cuiller à pot pour demander la pluie’, Journal des africanistes, 76-1 | 2006. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/africanistes.192

Helman, Ivy. ‘Asherah and the Trees’, in Asherah: Roots of the Mother Tree. Girl God Books, 2025, citing Pass, Rachael. ‘Meet Asherah, the Little Known Jewish Tree Goddess.’ HeyAlma, 6 February 2020.

Kosnick, Darlene. History’s Vanquished Goddess: ASHERAH. Emergent Press, 2017.

Moriah, Lisa. ‘Asherah & Sarah: Where Divine and Human Merge’, in Asherah: Roots of the Mother Tree. Girl God Books, 2025

Shannon, Laura. ‘Thirst for Knowledge, Thirst for Rain: Women’s Seeds and Symbols in Southern Morocco‘ feminismandreligion.com, May 4, 2024.

Shannon, Laura. ‘Language of the Goddess in Balkan Women’s Circle Dance’, in Feminist Theology, Sage Publishing, 2019.

Shannon, Laura. ‘Um Regen tanzen: Lebensspendendes Geschenk des Himmels an die Erde’, in Neue Kreise Ziehen Fachzeitschrift für meditativen & sakralen Tanz, Heft 1, 2014.

Stone, Merlin. When God Was A Woman. Mariner Books, 1978.

Westermarck, Edward. Ritual and belief in Morocco (2 vols.) London: Macmillan, 1926.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My Asherah Pole is a literal tree in my backyard. But now I think the broom I keep for magical purposes should become another Asherah pole. Thank you for the inspiration! And the wealth of knowledge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! The Goddess as Tree is most ancient of all. But the broom is good too. As long as women have had household tools, these have been sacred, because since Neolithic times a woman’s home was her temple and she was the priestess. I love how any implement used by women for the sacred work of nourishment and taking care of living space – broom, ladle, pestle, pot-stirring stick, breadboard, winnowing fork, grain shovel – can be turned into Asherah in the moment of need. She is always with us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have worshipped Asherah for many years now. So seeing this post was refreshing and lovely. I always use actual trees for her. But I have a magic broom outside my front door for protection. And I actually have a dress from a broken porcelain doll.

And a magic stick that fell off the other day. I can add it to the brook for arms. And slip the dress right on. The broom is used to sweep the ground of any and all evil before ceremonies or magic. As per Wiccan traditions.

It’s not a Besom broom. But I have used it for cleaning. And then I used it for sweeping bad energy out for Hekate. So this should be perfect. Thank you for this!

I also made an article on Candlemas called the Black Goddesses of Candlemas. And I mentioned the Berber religion and how Canaanite Polytheism was also part of their culture. So all this resonates with me!

LikeLike

Your special broom does sound very appropriate as a pole for Asherah. Let us know how it goes! I would be interested to read your article on Black Goddesses of Candlemas too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I intend to dress it up soon. I did a ritual asking her for rain. A minor ritual. It hasn’t rained yet. But the sky got darker noticeably. So I am stoked and will do some divinations to see what I should do. Also the article is this one

LikeLike

Another thought: there are also the tent poles of the nomadic folk of the Maghreb and Near East, AND poles inside houses of settled people such as the Berber/Amazigh. They are common in old-style rural homes in Greece and the Balkans too, and are very often carved and/or decorated in a way to show they too are sacred. I wonder if this is another way reverence for Asherah survived in disguise in this part of the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Laura. During the focus on Mary Magdalen’s feast day, a memory of a Divine Feminine event brought a reading by and female Episcopalian Priest on the subject of Hebrews and how they had worshipped a goddess and the ‘one male god’ group had massacred all the goddess worshippers. Brought up by a Southern Baptist Mother I attended church on Sundays until College. Never once did I hear this story.

This year I wondered about who that Goddess was and found the name Asherah. I thought I’d like to know more about this and here you are. I will reread this article because it is so full of information and needs another look.

The removal of Asherah and so many others, and those remaining, downgraded, is why we’re on the brink of destruction now with the ‘one male wrathful jealous leader’ on the thrones of many nations.

My our prayers and wisdom open a doorway into a new world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I typed a comment but was interrupted with a prompt to log in. It seems to have vanished. But please forgive me if it magically resurrects after I enter this one. 😅

I wanted to thank you for this article which deserves more than one read. During the week of Mary Magdalene posts on Substack and Facebook, I somehow remembered hearing about the slaughter of the Hebrews that worshipped a Goddess at a Divine Feminine event a few years ago. In my many years of attending a Baptist Church with my mother (till College) I never heard this story told.

And I this past week I wondered who that Goddess was and how she was worshipped. I had gotten the name, and your post arrived to give me the rest. Thank you. ❤️

We are living in a time when the ‘one male wrathful, jealous god’ is sitting on the throne of too many nations, reaping the ultimate result of what started so long ago. The time seems dark. May our remembering, our rituals, and our prayers call the rain that brings the blossoming of a new world.

✨💙✨

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Shelliee,

Looks like both your comments came through just fine. Thank you for responding. You are so right, when we were young it is unlikely that any of us heard this story told in either Jewish or Christian contexts, but it’s our great good fortune that this is changing now. Merlin Stone’s book ‘When God Was A Woman’ was revelatory and life-changing for myself and many others, and is still a wonderful resource. We do need to know what happened, and to understand that patriarchy is neither eternal, universal, nor inevitable. Knowing that there was another, better way once upon a time gives so much inspiration and hope to try to create a better way of living now.

LikeLike

What a beautiful Taghnunja figure. The colors are fantastic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Annelinde, lovely to hear from you.

Yes! From the Musée Berbere in Marrakech, this little Taghonja figure is an old one, wearing a hand-spun, hand-dyed, handwoven shawl, of the kind brides used to wear in certain regions. And I love her hands made of ladles.

Every time I get the chance to visit this museum I spend a long time in front of this figure in awe.

LikeLike

I love considering women’s implements, especially brooms, as manifestations of Asherah. And I have a beautiful wooden ladle that I will now look at differently. Thank you. (It may be false etymology, but in Hebrew the ending “ja” or “jah” is a name of deity.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful to read of Asherah as consort to El/Yahweh, and the picture of balance and reciprocity this evokes. A glad reminder of joyful possibility in a world too much oppressed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

By closing your article with, “This water is there, for those with eyes to see. And it flows straight on”, you have asked us to realize Her power is still present in our own times. The connection between women and the Life-Giving Goddess(es) is real and vibrantly alive.

Marija Gimbutas asserts, In The Language of the Goddess that the ancient Paleolithic ancestors of Old Europe “created a deity who was a macrocosmic extension of a woman’s body”. Gimbutas explains the symbolic associations: “the mysterious moisture in the uterus and the labyrinthine internal organs of the Goddess were the magical source of life” and that the people of that large region embraced the prevalent belief “that all life comes from water”. I would add Carol Christ’s comment that often the people could observe that water comes from the rain clouds emerging from Her sacred mountains.

We, the women of today, can all benefit from every reminder that “The Goddess is alive and magic is afoot” to quote a 1970’s women’s spirituality chant shared by women all across the US.

You tell us you have experienced the success of these rituals, that is, rain showering the joyful women in southern Morocco before they even finished their Taghonja ceremony. I was especially moved by the images of the wooden ladles (serving as arms) of the Taghonja figure prepared to receive the rain and to have it flow in abundance to all who needed it. That image from the Museum of Berber Arts will long remain with me—especially now that I understand the symbolism. Your talents as a “textile translator” are much appreciated.

Your description of the dancing women and girls sharing their laughter and joy in anticipation of more laughter and joy when the rains fall becomes a model for our own actions.

LikeLiked by 1 person