For most of cinematic history, the moral universe of film was anchored in clarity. The hero was dharmic—principled, disciplined, and guided by a moral compass that was neither ambiguous nor negotiable. The villain, by contrast, represented a clear rupture in the ethical order. Actions had consequences; justice was intelligible; human beings possessed agency, responsibility, and accountability. Main stream cinema reflected a world in which right and wrong, virtue and vice, were not merely narrative devices but metaphysical coordinates. One could locate a character on the map of moral compass with precision.

Older Indian cinema often adhered to a strong moral framework in which even the most charismatic or beloved protagonists were ultimately required to pay for their transgressions on screen. Unlike today’s era of morally ambiguous films—where anti-heroes may triumph, consequences are negotiable, and ethical lines are intentionally blurred—classic cinema rarely allowed wrongdoing to go unpunished. Yet this does not mean that earlier films lacked sophistication or ambiguity; rather, they explored moral conflict within a clear ethical horizon, allowing audiences to empathize deeply with flawed characters while still witnessing their inevitable downfall. For example, in Deewaar (1975), Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay becomes an iconic rebel whom audiences passionately sympathize with, yet he must die in the end to restore moral order. In Parwana (1971), his obsessive, morally dark character meets a tragic ending, demonstrating the same principle. Even beyond Bachchan, iconic villains like Gabbar Singh in Sholay (1975) was originally written to die as a narrative necessity. Through such storytelling, older cinema balanced empathy with accountability, illustrating that complexity and moral clarity once powerfully coexisted.

The landscape of modern cinema, however, reveals a profound cultural shift. The once-stable categories of good and evil have dissolved into gradients of grey. The contemporary screen is populated not by villains but by relatable monsters: wounded, traumatized, misunderstood figures whose transgressions are framed as the inevitable consequences of personal suffering or systemic failure. Films like Joker, Shape of Water, Kabir Singh, and Animal do not ask the viewer to judge; they ask the viewer to empathize. Their protagonists blur the boundary between perpetrator and victim, collapsing the distance between moral agent and moral casualty.

This aesthetic transformation is not merely a stylistic evolution—it reveals a deeper shift in our collective metaphysics. When cinema normalizes the broken hero and the sympathetic villain, it participates in a broader cultural movement that destabilizes the categories of justice, responsibility, sin, and punishment. The moral world no longer functions as a stable structure governing human action; it becomes an emotional landscape shaped by trauma, subjectivity, and personal wounds. In effect, contemporary cinema enacts an erasure of moral order, dissolving the metaphysical distinctions that once made ethical judgment possible.

What is more of an ethical conundrum is that romanticization of Lucifer is also celebrated. When Lucifer is not merely a character, he is the archetype of rebellion against the moral structure of the universe itself. When culture begins to empathize with Lucifer, it reveals a desire to justify, beautify, and emotionally redeem moral transgression in its purest form.

These larger than cinematic figures don’t just work in vacuum but have a profound impact on our moral, psychological and cultural settings. Neuroscience research indicates that repeated exposure to violent media may lead to desensitisation i.e., reduction of emotional response to others’ suffering or violence.

Even the auditory dimension of cinema has powerful neurobiological consequences. Sound alone—without any visual stimulus—can activate the amygdala, heighten autonomic arousal, and trigger physiological responses such as increased heart rate, sweating, and muscle tension. In horror films, non-linear sounds, sudden sonic ruptures, and frequencies resembling distress calls stimulate primitive survival circuits in the brain, producing fear before conscious interpretation occurs. With the emergence of neurocinema, researchers have begun to demonstrate that sound design is not merely an aesthetic layer but a neurological instrument that shapes perception, emotion, and memory. Far from being secondary to visuals, auditory stimuli can hijack our nervous system more rapidly and more powerfully—suggesting that what we hear in a film may be just as important, if not more, than what we see. Seeing the impact of sound alone, how profound would be a morally skewed movies on one’s neurology. The growing field of neurocinema therefore deserves the momentum it is gaining, as it reveals how cinematic form is deeply intertwined with the biology of sensation and the architecture of the human brain.

The cultural shift does not unfold in isolation; it reveals a profound psychological and sociological phenomenon. In classical cinema the female’s narrative agency was often constrained (she was not the one firing the guns), her moral agency was immense. The entire story’s emotional and ethical weight often rested on her shoulders. The hero fought for her, or his downfall was precipitated by failing to protect her.

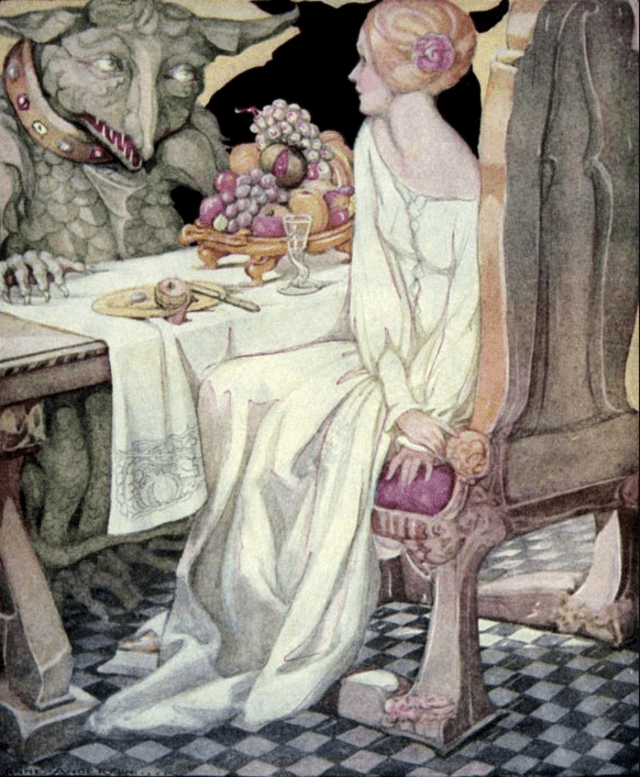

As the moral universe of cinema dissolved into “gradients of grey,” the female role shifted dramatically. She is no longer the conscience the hero answers to, but the saviour who absolves the anti-hero of the need for one. In contemporary cinema, women are increasingly portrayed as the redeemers of broken men: the nurse of wounds, the saviour of rage, the balm to brutality. The feminine becomes a sanctuary for the monstrous masculine, a space for moral rehabilitation. Films like Animal, Kabir Singh, Joker, and Beauty and the Beast construct a fantasy in which a woman’s love is the alchemical force capable of transmuting violence into tenderness. It removes the final judgment, celebrates the “relatable monster,” and makes the female’s redemptive role the central fantasy.

The journey from the classical to the modern female role is not a simple story of progress from “passive” to “active.” It is a shift from one kind of power to another, and from one kind of burden to another.

In this aesthetic economy, women are not only viewers — they are discipled into a moral imagination that equates suffering with depth, brutality with intensity, and toxicity with love. To heal the broken man becomes the ultimate feminine calling, and in doing so, the responsibility of moral transformation is transferred from the agent of violence to the object of his affection.

The psychological infrastructure that enables women to romanticize the monstrous does not emerge in adulthood; it is cultivated in childhood, long before one has the language of ethics or the consciousness of choice. Disney, the most powerful myth-making engine of the past century has played a pivotal role in constructing a romantic aesthetic in which love is synonymous with rescue, sacrifice, and suffering. Beneath the glitter of castles and ballrooms lies a subliminal pedagogy: the normalization of violation as romance.

Consider Beauty and the Beast: a narrative where a woman falls in love with her captor, where confinement is reframed as devotion, and where transformation is purchased through the emotional labour of a woman tasked with redeeming a violent, emotionally dysregulated male. Stockholm syndrome here becomes a fairy tale.

In Sleeping Beauty, the heroine is kissed while unconscious — an intrusion without consent reframed as an act of salvation. The narrative teaches that a woman’s body is passive, and a man’s entitlement to it is heroic.

In The Little Mermaid, a young girl literally sacrifices her voice, her language, her identity in order to win the affection of a man she has never spoken to. Silence becomes virtue. Self-erasure becomes romance. These narratives embed themselves in the psyche long before critical thought develops. They form what psychologists call “attachment templates” — unconscious blueprints that shape what we later recognize as love.

BIO: Sabahat Fida I am an educator based in Kashmir with masters in the field of zoology and philosophy. My work has appeared in The Wire, The Swaddle, The Hindu, Erraticus, Metapsychosis, and Daily Philosophy. I write on the intersections of science, religion, philosophy and metaphysics.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.