I never considered myself one of those people who gets really “into” Halloween. But, as one might expect having an eight year old, especially an eight year old who celebrates her birthday shortly before the holiday, has made me much more in tune with the excitement and preparation which surrounds Halloween.

One of the traditions that I do very much enjoy is watching Halloween movies like Hocus Pocus and Double, Double, Toil and Trouble and, new to us last year, drinking warm mulled wine after coming home from a chilly (and this year possibly snowy!) night of Trick or Treating.

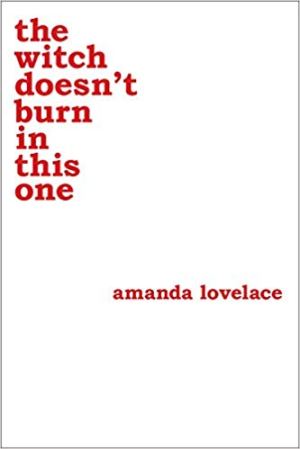

In my work as a church musician Halloween is book-ended by the celebration of Reformation and All Saints Day, so it tends to be a fairly busy time for my work schedule. As a result this is often the time of year that I reconsider my self-care and centering routines in the hopes of somehow preparing myself for the coming holiday season and the end of the year. This year, as I checked in on my current practices I realized that I haven’t been reading as much poetry as I used to when I was in grad school. As a result I have been trying to get back in the habit of reading some poetry a few times each week to help center myself. As luck would have it the last few weeks have found me stumbling upon poetry with connections to the Halloween season. I want to share with you a portion of two seasonal poems that I have encountered and are sticking with me.

Continue reading “Double, double… rhymes are trouble by Katie M. Deaver”

In folklore Old women are believed to control all aspects of Nature – Fire, Earth, Air and Water, but in myth and story they have a special relationship with water.

In folklore Old women are believed to control all aspects of Nature – Fire, Earth, Air and Water, but in myth and story they have a special relationship with water. Continued from

Continued from  My book club recently read

My book club recently read