One of two pieces on Joy, part 2 tomorrow.

Joy was not a conspicuous presence in my childhood home. My parents were kind and loving, but both had been raised in the Protestant conservatism of rural Alabama during the Depression years. Laughter, contemporary music, dancing, drinking—none of these were part of my growing up years. Attending church was our primary social activity. I started middle school in the mid-1960s having never heard of the Beatles, Chubby Checker, or the Twist.

Instinctively, I felt that there must be more to religious experiences than the dull passivity of listening to an old white man lecture on details of an antiquated religious text. Psalm 100 in the Hebrew Bible instructs us to “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord,” but I couldn’t find joy anywhere in my home church. Even my relationship with Jesus, which felt sacred and special, was dimmed by the constant focus on Jesus’ suffering and death and my concurrent obligation to avoid sin at all costs.

I left church in college and became a Hippie. Woodstock provided my first opportunity to engage in the ecstatic experience of collective joy and I reveled in it. Somehow this multi-sensorial event, shared mostly with strangers, stimulated my every sense to the fullest and left me both completely drained and joyfully renewed. The best part was the feeling that here, among these thousands of strangers, I had finally found my tribe.

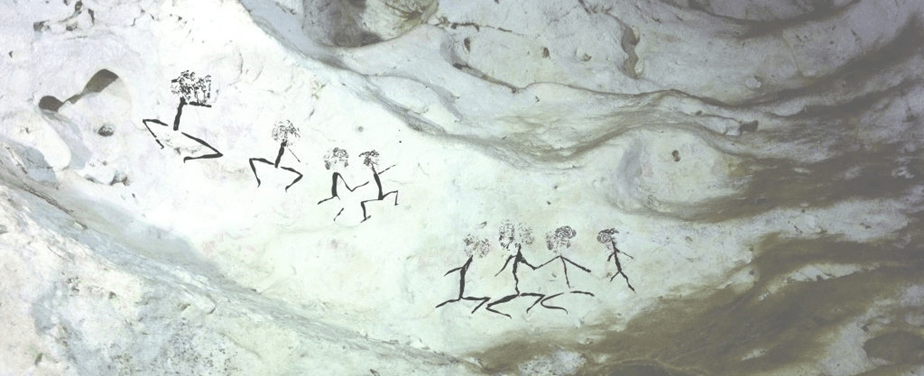

I believe that collective joy is part of our birthright as humans. In her wonderful book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, Barbara Ehrenreich observes that prehistoric rock art depicting dancing figures has been found on six continents. Life was hard over 10,000 years ago but our ancient ancestors considered their danced celebrations of sufficient importance to record in art. Anthropologists believe that such experiences of collective joy served to create spiritual bonds among individuals and communities and helped ensure their survival. I believe that their understanding of both divinity and the world around them emerged from their danced ceremonies.

For millennia, such shared ritual experiences marked all human life across the planet. These worship experiences were very different from ours today, where we mostly sit passively and listen. Ancient sacred rituals were inclusive and participatory. Everyone got involved in both the preparation and the celebration. Our ancestors had direct ecstatic experience of the sacred which created and supported their sense of connection to each other, life itself, and the cosmos. Their experiences were not mediated through a ruling priesthood. Such experiences still occur in the few remaining indigenous cultures on this planet.

In western Europe, such experiences were common down to the time of Greek civilization. But the Romans initiated profound changes in how the gods were worshipped. As Roman culture expanded and evolved, it became more hierarchical, misogynistic, and militaristic. Dance and ecstatic celebration—arenas in when women and men participated equally—fell into disfavor. Upper class Romans prided themselves on being sober, rational and logical. The elements of ecstasy, such as drumming and dance, were deemed “utterly unseemly and unworthy of a nobleman’s sense of honor,” according to sociologist Max Weber. In addition, citizens busy dancing in the streets worked less and were harder to govern and control. Official Roman religion evolved to reinforce the emerging social hierarchy. Rituals were led by a specialized hierarchical male priesthood. When the emperor declared himself a god, the bonding of religious and secular authority was complete. This pattern of merging secular and religious authority was subsequently adopted by Christianity as it spread across Europe. The wildness of ecstatic ritual was outlawed and gradually eliminated from the culture.

Dr. Jalaja Bonheim, author of The Hunger for Ecstasy, writes “That state of rapture, of bliss, of feeling totally in love with life is an essential nutrient without which we cannot thrive.” This very human need for ecstatic experience regularly comes into conflict with the patriarchal need for power and control. Throughout history, and across cultures, the same drama is enacted, with different players—priests and peasants, Puritans and witches, missionaries and indigenous peoples. The need of the patriarchal upper classes to maintain power and exercise control over lower status groups is often paramount. This is true whether we are talking about business and factory owners, dogmatic religious leaders, or power-hungry politicians. Over the centuries, countless laws have been passed trying to rein-in the wildness of ecstatic celebration.

As it turns out though, the human desire/need to gather in the streets—to mask and drum, dance and sing—is harder to eliminate than one might think. In the Middle Ages, the church found it easier to compromise—to allow the laity to dance when and where they wanted, as long as it wasn’t in the church. And thus Carnival was born.

The intense sense of connection with each other, the Divine, and the Cosmos that can be achieved during danced rituals is something most spiritual seekers desire. “Ecstasy is neither a luxury nor an aberration.” Bonheim writes. “It is our birthright.”

This fundamental conflict between the patriarchal need for control and the human need for joy and ecstasy continues today and is a critical part of our heritage as Americans. Opportunities for collective joy are not part of our shared spiritual experiences. Some argue that civilization and ecstatic ritual are incompatible. We have become a consumerist society which acquires most of its pleasure through consumption of the new and entertaining. We are starving for something and we don’t even know what it is.

Nevertheless, within this spiritually restrictive environment, ecstatic ritual continues to find a place. Festivals of many kinds are populating our landscape—from Burning Man to the Michigan Women’s Music Festival, from Reclaiming Witch camps to Gay Pride parades. People are reclaiming their right to find, create, and participate in ecstatic rituals that feed both their souls and their desire for community.

In some fundamental way, the patriarchal need for status and control cannot suppress human desire for community and creativity. As in the Middle Ages when festivals were creative exercises engaging many talented individuals, so today our innate creativity bursts through in the many forms of celebration we have created to help us connect to others, as our ancient ancestors did.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for this Mary. There’s a full blue moon tonight. As I live on a cliff overlooking the sea in Wales, I’ll open the balcony door of my apartment and imagine dancing on the path of golden light that eventually turns silver across the water from Wales to the Somerset coast in England. In 3 weeks we have the autumn equinox, when I shall celebrate the end of the harvest and the change to autumn with a small local druid group. I totally agree that joy is part of our birthright, which we seem to have forgotten. British and Irish Celtic culture’s changing seasons and fire festivals still offer me sacred time and space to experience the music in the earth, my soul, and the universe. It’s both life-giving and inspiring to tune into nature’s rhythms, and who would want to harm a planet they dance on?

LikeLiked by 2 people

“In some fundamental way, the patriarchal need for status and control cannot suppress human desire for community and creativity”.

I am having a hard time believing this is really true today… I just read that the EPA has rolled back the protection of our federally protected streams wetlands etc – our only buffers against extreme flooding and pollution… our govt is working against us… patriarchy will fall eventually but not until it’s too late. No dancing for me.

LikeLike

I’m recovering from a total hip replacement post bilateral mastectomy + DIEP flap reconstruction and chemo after being diagnosed with cancer.

I’m quite looking forward to being able to dance again.

I used to feel that I could not achieve ecstatic states.

This morning feeling my delight bubble and bloom whilst being serenaded by magpies as I performed some of my morning prayers on the crisp last morning of Winter (Southern Hemisphere), I wonder if perhaps I was just overthinking it.

LikeLiked by 1 person