Are you planning to gather with family or friends to celebrate during the holiday season? For many, this idea elicits joy, but for others, it evokes tension, dread. Some may even think, “Ugh, I don’t want to deal with the drama.” The reaction is real. Elucidating a psychological concept related to such dread sheds light on this “drama” and may help you manage tense and potentially provocative situations over the holidays.

Stephen Karpman developed the concept of the drama triangle in his 1968 essay, Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis. He looked at the stories that cultures tell, considering how these stories instill images, roles, and demeanors in the social imagination, which then manifest in individual and group behavior. The narrated plot lines work on the unconscious to provide attractive stereotypes: the helpless (as a human) mermaid Ariel makes a deal with a Sea Witch for legs; she becomes human but loses her voice in exchange – a voice restored due to the true love of a prince. Cinderella, the stepdaughter working amidst the ashes for the evil stepmother, wishes for more, and viewers watch as a prince eventually arrives. Stereotypical Barbie faces an existential crisis; she, like Ariel, finds power in human form, and corrects the wrongs of patriarchal society against both doll and owner. Every drama presents a triangle.

Let’s expand, following Karpman, on Cinderella:

In Cinderella, the heroine switches from victim double persecuted (by her stepmother then stepsisters), to victim triple rescued: the mice help her; the fairy godmother produces the dress and carriage, and, and then, in the end, the prince appears. But she becomes a victim, persecuted again, when the clock strikes midnight, and then a victim rescued again when the prince brings the slipper which saves the day and her life, delivering her from further persecution by the stepmother and stepsisters. A rough quantitative analysis can be made of the intensity of the drama for Cinderella by totaling up the switches (8 of them).

Eight times, Cinderella is a victim either at the hands of a perpetrator (a person or thing) or at the hands of a rescuer (also a person or thing).

Dramatic roles such as victim, perpetrator, and rescuer transpire in greater and lesser degrees of intensity. As in Cinderella, the triangle begins and facilitates the drama through roles changes. The storyline progresses as a result of these changes in roles. Cinderella’s conundrum and its persuasiveness (one day her prince will come!) relies on role switching, without which the storyline fizzles. So, to keep energy moving, to keep the drama in play, the roles have to continue to be observed and exchanged. Even one person’s rejection of a role can alter the lifespan of the drama. If Cinderella said, “Well, that’s it. I just want to be in the woods by myself,” or “No thanks, fairy godmother. I don’t want the dress,” the story would end. Thus, the triangle captures her in the various roles until the story comes to fruition; otherwise, the triangle persists.

The triangle also appears in our personal lives according to Karpman. To uncover where, he suggests naming and then thinking about a favorite fairy tale or film. Analyzing the key drama and the parts the characters assume (and to which you may feel partial) reveals key roles that play out in our individual narratives.

Sociologists, like Peter Berger who argues for the dialectical phenomenon, see the exchange going both ways. Fairytales, drama, and fiction also reflect the ways in which roles and stereotypes operate in society and get absorbed to be portrayed in fiction. Karpman thinks that this reversal happens less often.

Either way, dramas in our lives assume similar characteristics to fiction and continue as long as we participate in role switching. In such cases, we and those close to us move in and out of personas that look like perpetrator, victim, and rescuer. This is especially true if we have an experience of family drama, or a trauma history. A simple, and not too intense, example occurs in the movie, Home for the Holidays. Brother Tommy (perpetrator) “accidentally” throws a turkey onto his perfectionist sister Joanne (victim). She berates him (perpetrator) and cries (victim again). Her husband, Walter, attempts to mollify her (rescuer), and her mother runs to get something to clean the dress her daughter is wearing (rescuer). If, instead, Joanne had laughed when the turkey fell into her lap, or even just walked away, the triangle would have failed to be develop, and the drama of the scene would have diminished.

Ultimately, in both real life and the fictional narrative, the triangle has the potential to reflect a dysfunctional process that entraps us. When a trauma history lies behind the role changes, the triangle can absorb us into a dynamic that is difficult to escape because the roles operate intrinsically and function without our conscious awareness. The roles are sneaky, fluid, and change at any time.

The challenge: make the roles conscious in real time, and step outside of the triangle. The play ends when we refuse the roles. Once in Home for the Holidays, during some family drama, the protagonist Claudia (sister to Joanne and Tommy) whispers to herself, “floating, floating.” While this can be a mode of dissociation, the words function here as a conscious reminder to disengage and not participate in the role Claudia is invited to take by her mother to engage in the triangle.

If you have ever felt insulted or harmed, and then suddenly realize you have been made the person at fault, you have been similarly invited into the drama triangle. Unless you step out of it, the reactive quality of this drama perpetuates its repetition in any given situation and then from one relationship to another.

Stepping out of the drama triangle is more complex than recognizing the triangle itself. But a few things can help.

- Name the process: “I have assumed the role of the victim in this scenario.” Or, “I tried to rescue my sister.”

- Foster awareness of when the feeling of any role appears: guilt, shame, frustration, and helplessness can be warning signs.

- Examine the situation, the changing roles, and be an agent: decide if and when you are in a role and when you are not. Make role assumption a choice.

- Chose to assume none of the roles and step out of the triangle all together. Joanne could have stood up from the table to go change. The scene would have ended right there: bad for the movie, good for character health.

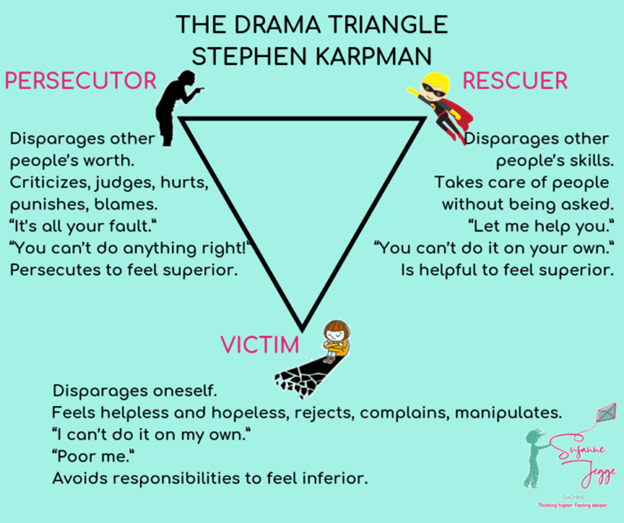

Sometimes the stepping out is more difficult than it appears, and confronting a final choice becomes necessary: leave the dramatic triangular relationship altogether. The latter is especially the case when the triangle shows up in every or most interactions between two people. There are many images of the drama triangle online, but I like this one for its straightforwardness:

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks, Stephanie, for this post. As someone who seeks “authentic” interactions and experiences, am sensitive to being thrust into the role representing any side of the triangle. Love this: “Chose to assume none of the roles and step out of the triangle all together.” Not always easy to do, but works well to de-escalate should tensions rise in social situations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Esther for this comment. I am struck by the word “deescalate.” I like it. A term that would be used in trauma theory would be to regulate – or moderate arousal. But I like the social implications of “deescalate” and the possibility stepping out of the triangle offers not to fix situations but to allow the deescalation of tension in social life to possibly promote conversation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have often been blamed /blame myself ( same thing) ….age has allowed me to simply remove myself from those that would harm me …. at the same time I assume responsibility for my 50 percent – holidays are meaningless to me now except for the rituals I have created myself and I am so so grateful to be out of the fray.

LikeLike

Thank you Sara. I hope Thanksgiving offered some time to engage in such rituals – if you have one for it!

LikeLike

I do…. I celebrate thanksgiving at the fall equinox… as many Native peoples do.

LikeLike

What an insightful post! And I think it is especially relevant to women who get pushed into these roles almost from the beginning of life. I wish I had learned to see how “drama” is created and the skill of walking away from it when so much of society is based on women staying within it 60 years ago. Thank you for writing this post and sharing it with us.

LikeLike

Thanks Carolyn. I didn’t think about the experience of women being used into these roles…and yet, all of my examples are of women. Somewhat due to the framework of the blog, but actually, they were so easy to find…I will have to think about that more as a conditioning process in social life. In appreciation, Stephanie

LikeLike