This summer I had the opportunity to travel to Fire Island, New York, which is a long sand bar full of small beach towns with no cars. Fire Island’s been a haven not only for beachgoers but for queer folk for many decades. We stayed in the town of Cherry Grove with friends, and one night we went out to look at the supermoon/blue moon. The moon rose over the horizon, red and a little scary, a sight like none of us had ever seen. Not far from the moon was a star so bright it came out in the photographs. I wondered if that was the morning star. Venus, in our current understanding. Inanna or Ishtar, among some of the ancients. And that made me think of Istehar.

Istehar, in Jewish legend, is a maiden who became one of the Pleiades. Her legend is unusual among Jewish legends because it reads like a Greek myth. It takes place during the time when some angels had descended to earth because they desired human women. One of these angels, Shemhazai, noticed a certain woman named Istehar, and desired her and wanted to be intimate with her. Istehar wished to flee this angel, and so she said: “I won’t accept you as a lover until you give me your wings and teach me the Divine Name that allows you to fly to heaven.” The angel gave her his wings and taught her the Divine Name. Istehar immediately uttered the Name and flew up to the sky, thus escaping the angel. God was impressed by her virtue and decided that she would be placed among the seven stars, in the constellation of the Pleiades, “that humans might never forget her.” (Legends of the Jews I:4:11).

There are many surprising things about this legend. First, the name Istehar is clearly a reference to Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess embodied in the morning star. Of course, it also references Esther, the heroine of the book of Esther and the story of the Purim holiday—but the name is more strongly reminiscent of the goddess. Second, the legend reminds one of the legend of Lilith. In that story, Lilith, Adam’s first wife, uses the Divine Name to fly away from Adam, because she does not want to lie beneath him. She leaves the Garden of Eden and goes to the Sea of Reeds and abides there, choosing to become a demoness. In traditional Jewish sources, Lilith is a villain, who later kills infants in their cradles and steals men’s seed. Istehar is clearly a hero, a model of “purity,” but the two stories are very similar—women who use their mystical knowledge to avoid men, and become mythical beings instead. And finally, the legend that she becomes a star falls in line with Greek legends of women who are transformed to escape the lust of men, satyrs, or gods—like the river nymph Daphne who becomes a laurel tree to avoid Apollo, or the wood nymph Syrinx who becomes a reed to avoid Pan. In Greek myth, the Pleiades themselves are nymphs that Zeus turns into stars to rescue them from the hunter Orion.

I think Istehar’s legend always compelled me, from the first time I heard it. I loved that her name was so close to Ishtar’s, and that she chose her own fate—she made a good feminist heroine. And even more, I think I loved her flight to the sky—her claiming of the mysteries of heaven as her own. In Jewish lore, the Divine name is used for magical feats, and Istehar is one of the only named women who learned this secret. Something about that spoke to me. In my book Sisters at Sinai, the angel Gabriel tells queen Vashti the story of Istehar at a crucial moment, to inspire her to flee a situation that has become unbearable. But somehow I wasn’t finished with her story.

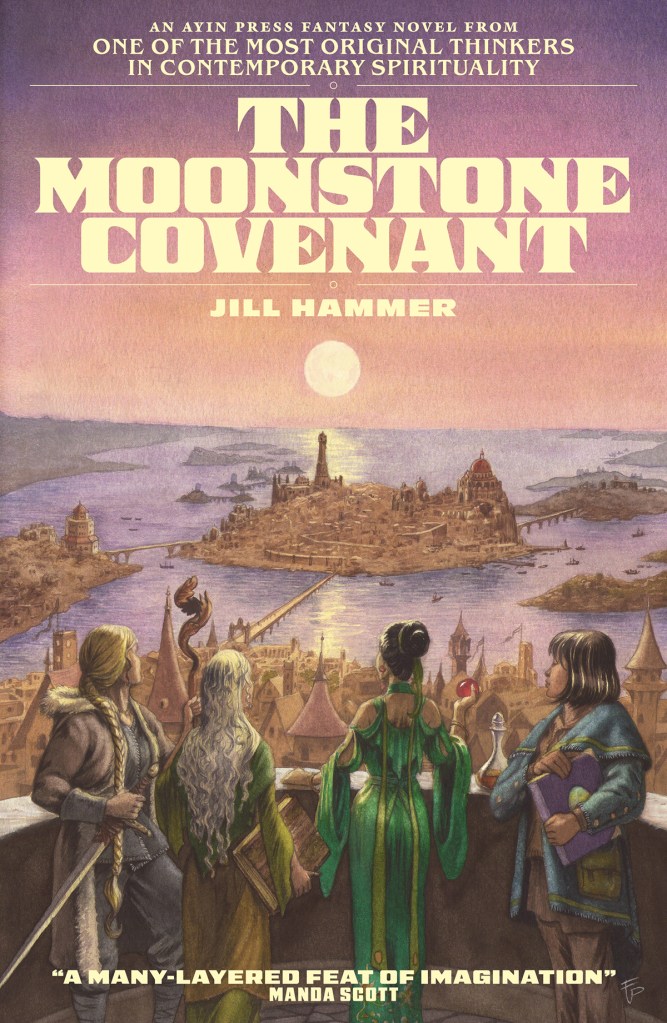

During the pandemic, living and working in a small New York apartment with my wife and daughter, I wrote a novel. I worked on it in the evening, mostly for fun, and discovered I really loved the story. It’s called The Moonstone Covenant, and will be published by Ayin Press this November. It’s about four women, all married to one another, who are living in the enchanted and dangerous archipelago city of Moonstone. One is a warrior librarian who tends the Library that is the world’s repository of wisdom; One is an apothecary. One is a former concubine with political acumen and magical skills, and one is a refugee mystic who can speak to trees and books and has led her forest people to the city of Moonstone for shelter after their forest was destroyed. This last character, who is the first to begin speaking in the book, is called Istehar. Guided by a mysterious book, the four of them set out to protect Istehar’s people and solve a double murder and end up transforming not only their lives but the city of Moonstone itself. It’s a feminist book, in the sense that its characters live in a world mostly dominated by men and yet have chosen a life with one another—and to support each other in the full exercise of their agency and gifts.

As I was writing the book, I told myself I wouldn’t think very much about why I was writing what I was writing—that I would just let the story unfold. But now that I am looking back on it, I can see in the character Istehar some of the wisdom, secret knowledge, and magical capacity I imagine in her mythic predecessor. I can see that Istehar’s journey in my novel parallels in some way the skyward journey of the Istehar of Jewish legend. It’s clear now that the story of Istehar planted itself in me like a seed long ago, and continues to blossom in new ways.

You can learn more about The Moonstone Covenant at themoonstonecovenant.net and can preorder here or here.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“The moon rose over the horizon, red and a little scary, a sight like none of us had ever seen.”…. Scary? – Absolutely – You are looking into a very polluted sky suffused with particles that clog our lungs and affect our breathing….. on another tack I thoroughly enjoyed reading your mythology and am struck again and again by the same theme – bird goddesses that must take flight to avoid capture…. women with wings…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this post. Istehar’s legend compels me as well. I love the idea of women who use mystical knowledge to stay true to themselves and follow their own paths in life. I am also intrigued by how her story intertwines with so many other myths.

And congrats on your book. I look forward to it. It sounds like a fun read.

LikeLike

What impresses me about the story of Istehar is how she uses a fairly transparent subterfuge against a male to get what she wants rather than what he wants, and he isn’t clever enough to see through it. Rebecca fooling Isaac into giving his blessing to Jacob by dressing him up as Esau?

LikeLike

GOSH I DISLIKE TRICKERY AND WOULD PREFER NOT TO USE IT –

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments, everyone. I do like the theme of wings in these “flight” stories. I’m thinking about the goddess Inanna’s theft of mystical and cultural knowledge in the story of her and Enki, and how all of these stories are in some way iterations of that myth….

LikeLike

I want to read your book.

LikeLike

I hope you enjoy! It is available in preorder– link is at the bottom of the article.

LikeLike

The mythic trickery motif isn’t always a moment of deception, though it can be of course when necessary and when facing the rape of patriarchy, but also of women’s ability to shamanically shapeshift. It’s not only a story of outwitting the enemy, it also highlights her access to multiple elements of her own consciousness, of adaptability to her environment, and to her innate ability to commune with multiverse. I haven’t heard this one before but I thank you for shining light on her brilliance.

LikeLike