Grief is the experiencing . . . Mourning is the process,

when we take the grief we have on the inside and express it outside ourselves –

writing, planting, burying, burning, rising up

ceremony, ritual, community[i]

“As long as I stayed there, I could keep you with me. . . .” Those words kept repeating in my mind throughout my long drive home from my sister, Jeannie’s, “Celebration of Life” service. I’d stopped midway on my thousand-mile journey at the cabin our family has shared for sixty years. There I could still feel her presence — on the hillside where we so often sat with our morning cups of tea, or watching the sunset, or chatting away the afternoon; on the dock where we’d lie in the sun or sit late at night and watch the stars come out, or cuddle up in blankets on windy, fall days; in the circle of couches and chairs where we played telephone Pictionary, charades, and CatchPhrase; in the kitchen where we’d cooked and eaten and played card games together; in the bedroom we often shared with a dog between our beds; the road where we’d go for family walks – eight, ten, twelve of us all together, and always two, three, or four dogs; even the driveway where we’d greet and hold each other with great gladness after months of separation, and where we’d hug and say goodbye, and then hug once more because in the back of our minds we’d be wondering if this was the last time. . . .

But as I closed the cottage door one last time, I felt our together life closing behind me, and the sobs that I’d contained for days rose loud and hard, and accompanied me as I drove away. For mile after mile, hour after hour, in what felt like a funeral procession, the trees appeared, dressed in their brightest finery of reds, yellows, oranges, and greens, lining the roads as if to pay their respects. I could sense them bowing, silently paying homage, all of them inviting my grief to flow.

In many ways I had been grieving the loss of my sister for several years as she slowly lost more and more of her mind in ways that drastically changed her personality and our relationship — our conversations changing from long, intimate exchanges to short and stilted chats monitored by her husband. But this final loss was different, for even the week before we could still hug and hold and laugh and cry. Now these, too, were gone.

Since my sister’s death, my mourning, even my experience of grief, had been put on hold for the two weeks when there had been photos to gather, an obituary to write, a service to plan, a eulogy to pen, meals to plan, accommodations to make, miles to travel. We went through the traditional rituals of mourning in white Western Protestant culture – gathering at the church she had attended for so many years, the pews, of late mostly empty as the congregation has dwindled, now filled with family and friends. My son sang, her grandson played his cello, her sons and I spoke our love. But with so much of the responsibility for that day resting on my shoulders, this was not my occasion to mourn. Others could listen and weep and mourn and gather after the service and share stories of their dear friend. Yet, strangely, even as we gathered that evening as a family we didn’t do that. We hardly talked about my sister at all, but instead caught up on each other’s lives. Perhaps we just needed to be together, or perhaps clinging to each other in this way was our manner of mourning.

In mainstream US culture, we allow ourselves so little time and space to mourn. Home once again, there were schedules to keep, mail to sort, bills to pay, clients to see, appearances to keep up. Life had gone on as I stepped out of time and now had to run to catch up, but I felt out of step with its demands and rapid pace. I am better suited for the days when people wore black armbands for a year, maybe two, after the death of a loved one and people, like the trees, understood.

Anishinaabe culture prescribes specific rituals for the death of a spouse. My friend, who lost her husband two years ago, cut her hair, gave away all the furniture they had shared, could not look at her husband’s image for a year, and had a ceremony of release on the one- year anniversary his death. But what is the ritual for mourning one’s sister?

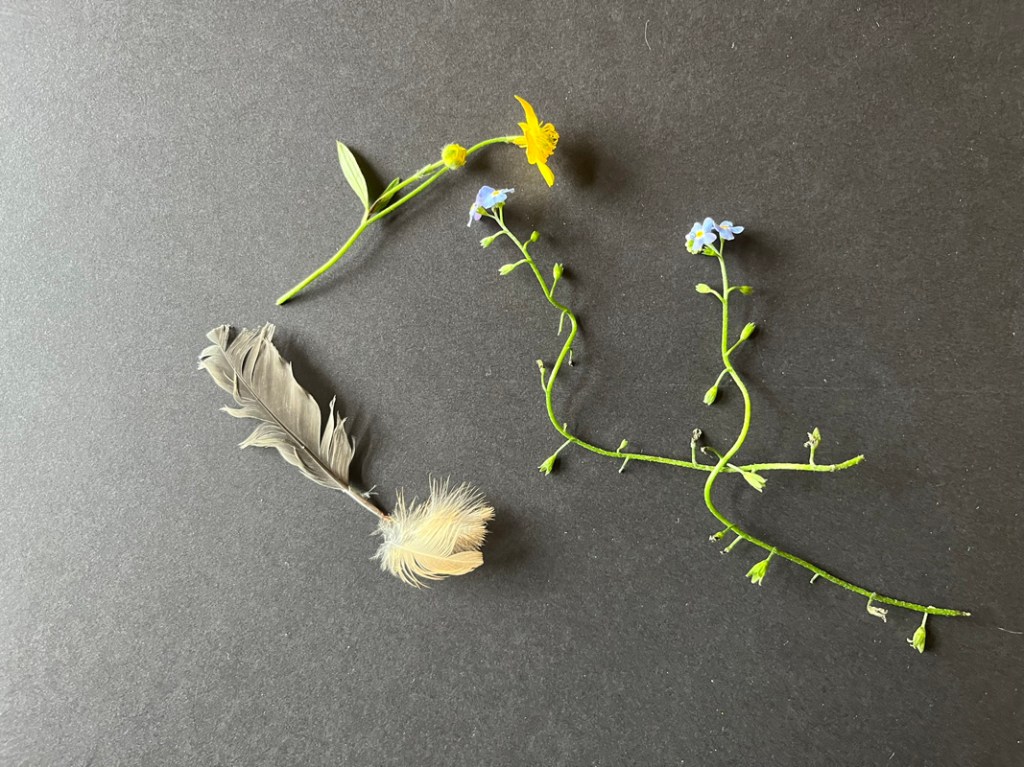

In the indigenous grief ritual taught to me by elders, the image of a circle is divided into eight parts. We name our griefs and place each in one of the parts of the circle. We color each piece with the hues our sorrow evokes and place on it the medicines – the herbs, berries, leaves, flowers, and feathers — we need to heal. This is the ritual of mourning I need. With all eight pieces representing my grief for my sister, in time, I’ll color them like the leaves outside my window, slowly turning from the green of life to the yellow she loved – how fitting that the earth is bathed in yellow right now – and on each I’ll place a feather for she who so loved birds. In the days to come, I’ll gather each feather that crosses my path and place it in my circle of grief, each one a token of my love.

As I began this piece, “Mourning is the process, when we take the grief we have on the inside and express it outside ourselves – writing, planting, burying, burning, rising up; ceremony, ritual, community.” This writing is the ceremony, the feather-gathering my ritual, and you who are reading this, my community. With gratitude.

[i] From the Indigenous Focusing-Oriented Trauma therapy handbook section on grief.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for sharing your journey with us Beth. What a brave thing for you to do. And in your own work, I feel you will be a guide and a beacon for others. We here at FAR are with you in your grieving.

“Mourning is the process, when we take the grief we have on the inside and express it outside ourselves – writing, planting, burying, burning, rising up; ceremony, ritual, community.” – such beautiful words which offer comfort and hope inside of sorrow.

May your journey be filled with love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Janet. This means so much.

LikeLike

I feel the love and am so grateful for this community.

LikeLike

Thank you for the distinction between grief and mourning. Jewish tradition also has formal mourning rituals, for specific time periods after the death. I like the idea of a personalized action to tune into grief.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to know more about those, Judith.

LikeLike

From Sara Wright: This is a beautiful and deeply moving essay. I think it is so important to understand that grief and mourning both are ongoing processes that occur in cycles. Indigenous peoples recognized this reality and honor the ancestors cyclically and those recently died with fires and many other complex ceremonies. I have never heard of the one you are using – but I think the idea is a sound one – that will help you stay with your grief until it passes this first round.

LikeLike

Janet, thank you for passing this along. Please let Sara know how much I appreciate her comment.

LikeLike

So beautiful. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Beth, Thank you so much for sharing both your grief and your so deeply meaningful mourning practice with us. What a wonderful way to both honor and celebrate your sister as well as find healing in Nature by placing elements that reflect your mourning journey in a circle, which has for millennia symbolized relationship and the eternally renewing nature of existence. Know that so many of us who have come to know and treasure you and your work here at FAR are holding you and your family in our hearts and prayers.

LikeLike

Thank you Beth, this could not be more timely, my sister is in final stages of terminal cancer, it is so hard!

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Carolyn. This touches me deeply.

LikeLike

I’m so very sorry, Cate. Yes, it is so very hard. Wishing both you peace in these final days.

LikeLike