On the eve of my 50th birthday, I found myself longing for my mother. She’d been dead thirty years—so long that I’d forgotten the sound of her voice or the temperature of her skin. And yet I missed her. Desperately. Shamefully.

The shape of that missing had something to do with the fact that I was nearing the age she’d been when she died. As a child, I’d watched my mother dress for a night of dancing with my father, lining her lips with red and stringing her neck with beads—sure signs she knew the secrets of being a woman: self-possessed; striding through the world with confidence and self-assurance; a real badass!

By now, I’d expected to feel that same sense of largesse. But the truth was that I still felt like the nineteen-year-old version of myself who had lost her mother, a child still waiting for someone to show me the way.

~*~

I wasn’t alone. My whole country seemed to have lost our way. We were surrounded by images of the feminine—pop icons and underwear models, feminists and porn stars, soccer moms and saints—all of them flashing large but pointing in different directions, unglued from whatever architecture might give them a coherent narrative: A blueprint that might hold us through the waters of our deepest anxieties. A guide who might answer our deepest questions: Who am I? Am I part of something larger than my own life? And if so, how do I fit within it?

~*~

In the absence of such a template, I’d turned to the gaze of a patriarchy that splintered us into a thousand versions while admonishing us that there was only one that would please. We could be smart or we could be beautiful. Chaste or voluptuous. A Madonna or a whore. As a child, my father had spouted off impossible lists of what a woman should be: She needed to be thin, but not too thin. An independent thinker who could discuss world politics, but from a liberal perspective, and always without interrupting. She had her own career but was also a great housewife.

“Control yourself,” I heard my father tell my mother whenever her behavior fell outside these rigid scripts, and his voice joined a chorus of others that urged my young self to look for direction in everyone’s mirror but my own.

~*~

I needed a larger mirror—and, at the age of 49, I traveled to Cuba to find it.

In Havana, I immersed myself in rituals that pay homage to the Yoruba river goddess, Ochún—a mighty mother who stands at the nexus of love and fertility, life and death. It is said that the river of her splits into a thousand tributaries, each offering up a different version of the goddess. There is Ochún Yeye Moró, the flirtatious one who loves to dance, and Ochún Ololodí, the deaf mermaid who doesn’t dance but owns the sixteen caracoles that divine the will of the gods. There is Ochún Niwe, who lives in the jungle. And there is Ochún Ibú Akuaro, who lives between river and sea and whose domain encompasses both fresh- and saltwater, just as her own identity can switch and change.

And in the small eastern town of El Cobre, I sought out Ochún’s Catholic counterpart—Cuba’s patron saint, Our Lady of Charity: A statue of the Madonna, just under a foot and a half tall and dressed in blue and gold. A chaste but watery mother who is said to swim each night with the river goddess before returning, still and unflinching, to her altar.

What interested me most were those Cubans who syncretized Ochún and Our Lady as if they were cut from the same cloth. The Catholics among them carry rosaries, while those who devote themselves to Santería wear the white cloth and beaded elekes that identify them as devotees of Ochún. All regale their version of the Mother with offerings of sunflowers, the most ubiquitous symbol that connects the two mothers.

I had never seen such nuanced devotion: one in which a woman did not have to choose between being one thing or another. She could be both a Virgin and a fertility goddess. A Catholic icon and an African spirit. Both earthly and spiritual. Sacred and profane. And it was this many-layered devotion that gave me the mirror I’d been longing for: a version of myself who could be both grieving and joyful, broken and whole. And a version of my mother who could be both flesh and spirit, dead and alive, boxed in by patriarchal scripts and brimming with the largest version of herself.

~*~

What did it look like to inhabit such a vast mirror? One that scratched beyond the surface role models we’d been handed to the very thing that generates and animates us all: a holy Creatrix capacious enough to reveal herself to us in all her guises: A beneficent voice urging us to lean into those places where we ourselves contain multitudes—to embrace those places where we are both chaste and sexual. African and European. Earthly and spiritual. Sweet and strong.

And what would it like to turn that gaze of generosity toward both ourselves and the world in a revolution of tenderness and grace and love?

~*~

These were questions I carried with me throughout my pilgrimage to Cuba, and into the pages that would become My Mother in Havana.

The result is a love letter—to the 19-year-old version of myself who lost her mother, and to the 50 year-old version who found herself missing her more than ever.

My Mother in Havana is a love letter to my mother who, behind the lipstick and heels, must have felt as lost and adrift as I. And it is a love letter to Cuba—an island that reached out to mother me.

My Mother in Havana is a love letter to every reader who yearns to claim a larger, more mythic life.

And it is a love letter to anyone who’s ready for a guide to show them the way: a wide-lapped mother both as real as the woman sitting next to you on the bus, and as vast and mysterious as the deepest river of your being: A feminine path to the divine that has been largely buried in today’s rush toward materialism & consumption. An open arm to hold you through any storm. A soft voice reassuring you that everything IS going to be all right.

My Mother in Havana was released yesterday, Feb. 18th. For more information and to purchase, click here.

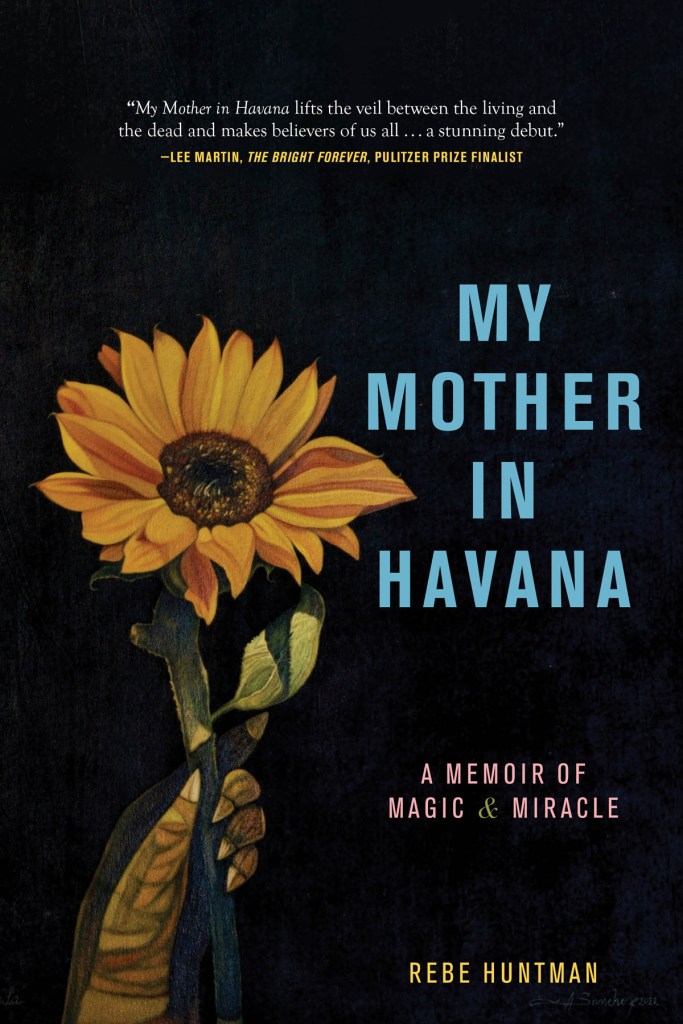

BIO: Rebe Huntman is a memoirist, essayist, dancer, teacher, and poet who writes at the intersections of feminism, world religion and spirituality. For over a decade she directed Chicago’s award-winning Danza Viva Center for World Dance, Art & Music and its dance company, One World Dance Theater. Huntman collaborates with native artists in Cuba and South America, has been featured in Latina Magazine, Chicago Magazine, and the Chicago Tribune, and has appeared on Fox and ABC. A Macondo fellow and recipient of an Ohio Individual Excellence award, Huntman has received support for her debut memoir, My Mother in Havana: A Memoir of Magic & Miracle (Monkfish Book Publishing Company, February 18, 2025), from The Ohio State University, Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Ragdale Foundation, PLAYA Residency, Hambidge Center, and Brush Creek Foundation. She lives in Delaware, Ohio and San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is where we see the importance of finding a myth that resonates to help us find a mother… I think most of us on FAR have these stories… however they may manifest – what’s important is that these myths show us how to live more sanely In my case as a mythologist many myths resonate….a coherent narrative in the culture? There isn’t one. The sanest approach is to distance oneself as far as we can. Myth lives – our culture will not.

LikeLiked by 1 person