Right before Passover every year, my wife and I visit a botanical garden to look at the spring flowers: daffodils, tulips, cherry and apple blossoms, magnolia. One year, in 2004 or so, we were on our way there when I had an idea. I grabbed a pen and started scribbling long lists of biblical women.

“What are you doing?” my wife asked.

“Making an Omer Calendar,” I said.

Since biblical times, there is a Jewish practice of counting the forty-nine days between the holiday of Passover (the barley harvest and festival of freedom) and the holiday of Shavuot (the first fruits festival and the season of receiving Torah). These forty-nine days were the time of the barley and wheat harvest and were a fraught time for biblical farmers. According to the Talmud, each day of the Omer must be counted along with a blessing. One must count consecutively each day (usually in the evening) and one loses the right to say the blessing if one misses a full day of the count. The Omer is often understood as a time of semi-mourning because of plagues said to occur during this time, but it is also a joyful season when nature’s abundance is at the forefront. This seven-week period embodies both fear that the harvest will be damaged and gratitude for the harvest.

The kabbalists, Jewish mystics tracing their history to a group of practitioners and writers in Provence and Spain in the 12th and 13th centuries, added their own ritual flourish to the counting of the Omer. For kabbalists, seven is a powerful number, representing the divine realms that were in communion with the physical world. The seven weeks of the Omer, according to the kabbalah, and connected to these seven divine realms, which are also known as sefirot. Sefirot (sing. sefirah) is a word that means spheres and also refers to the counting numbers, as the total number of realms is ten—the lower seven, which comprise the are what is being referred to in this essay).mmunion with the physical world. The seven weeks of the Omer, according to the kabbalah, and connected to these seven divine realms.

The seven attributes are:

Chesed: love/generosity

Gevurah: strength/rigor/severity

Tiferet: compassion/harmony/balance

Netzach: endurance/persistence

Hod: beauty/gratitude/surrender

Yesod: connection/the erotic

Malkhut: majesty/groundedness

Within each week, the seven days also correspond to the seven divine realms, so each day of the Omer embodies two nested attributes of the divine. For example, the first week of the Omer embodies love (chesed), the first day of the Omer is connected to the attribute of love within love (chesed shebechesed), the second day is connected to strength within love (gevurah shebechesed), the third to compassion within love (tiferet shebechesed), and so forth. In this way, each of the days of the Omer has its own unique spiritual quality, rising out of its combination of attributes. Those who count the Omer can meditate on these qualities and thus turn the practice of counting into an exercise in spiritual growth.

In kabbalistic writings, there are human personas associated with these different divine attributes. Most of them are male—for example Abraham the patriarch is associated with love/chesed, while King David is associated with malkhut (meaning majesty, kingdom, or grounded connection to reality). There are women associated with sefirot—for example, the biblical matriarch Rachel, like David is associated with malkhut. Also, the kabbalist Menachem Azarya of Fano did connect the seven divine attributes with the seven prophetesses named in the Talmud.

I wanted to expand this tradition by finding a biblical woman for each of the forty-nine days, one who would embody the unique combinations of attributes for each day. Throughout my life as a scholar and writer I’ve been obsessed with the stories of biblical women, and to me, this was the perfect opportunity to share those stories in a meaningful context. As we drove to the botanical garden, I frantically scribbled. The prophetess Miriam was clearly strength within love (gevurah shebechesed), given her courage in waiting by the Nile to save her baby brother. Hannah, who prayed at Shiloh to become pregnant, became tiferet shebetiferet–compassion within compassion, heart within heart. Naomi, the grieving widow in the book of Ruth who is redeemed by accepting Ruth’s devotion? Endurance within surrender (netzach shebe’hod). The queen of Sheba? Majesty within connection (malkhut shebeyesod), for her regal appearance in the court of King Solomon to explore wisdom with him. I began and ended the calendar with Shekhinah, the divine feminine, understood in the kabbalah as the divine aspect present in the physical world, encompassing mortal beings. This seemed to me to be appropriate to a calendar practice meant to honor the feminine.

Sometimes it was easy to fit a character to an attribute. Sometimes it was less easy. Who would be strength within compassion (I chose Deborah the prophetess) and who would be compassion within strength (I chose Lot’s wife)? I spent weeks refining the forty-nine days and their characters, but I continued to be guided by those first scribbles when I had the idea on my way to the botanical garden—that I could create a meaningful Omer practice that would also teach about biblical women. Some people asked me: are there really forty-nine women in the Bible? The answer is: yes, there are, and there were even some I didn’t manage to include. For each day, I created a description of the woman who went with that day, and an intention for the reader, inviting them to see themselves as connected to that woman and her atrributes.

By creating this practice, I hoped to expand the kabbalistic worldview, and the contemporary practice of individuals, to more fully include women in the ritual of counting the Omer. I also hoped to educate people about biblical figures who were not well known but who had amazing stories. And, I wanted to inspire people to try counting the Omer, or to find more meaning in the Omer-counting ritual if they were already doing it.

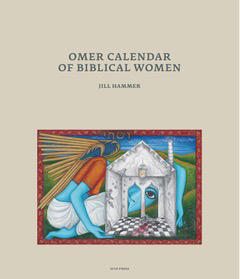

The calendar was at first published online as part of ritualwell.org. I got feedback from many people who said my calendar had revolutionized their experience of counting the Omer. Eventually, with the help of Rabbi Shir Meira Feit, I self-published a small hard-copy volume of the calendar, including seven images of biblical women, one for each week of the Omer. And now, Ayin Press has published a fabulous new version, just becoming available here. This version has a gorgeous layout and features some of the art in the original calendar as well as art from Siona Benjamin, an Indian-American-Jewish feminist artist whose images of biblical women have been shown all over the world.

The practice of counting the Omer remains important to me. The gratitude for harvest continues to resonate with me, as does the self-improvement practice innovated by kabbalists. And now I can also journey with a community of biblical women—and contemporary seekers who care about their stories. Today, as I’m planning my annual trip to the botanical garden to see the new blossoms, I’m grateful for the way ancient stories of women keep blooming in my life.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks, Jill. I just got my copy of the Ayin Press version this morning and am looking forward to Yocheved tonight.

LikeLike

I loved this essay and I learned so much from what you wrote highlighting the importance of where we stand as women now… I tried to comment when it was written but couldn’t bring up the comment section – technology is fickle I am starting to lose touch – can’t keep up with both and almost daily changes

LikeLike