In her Preface, Rollins writes, “Hypercontrolling my food and using exercise compulsively had always been how I coped with life, stress, expectations, and fear.” Many people (usually women) use this coping technique in their day-to-day lives. Controlling your body’s needs and desires allows you to feel powerful. I know. I am one of those people.

Powerful or being in control was not something the author felt able to achieve in any “normal” way given her upbringing “in an Appalachian [West Virginia] church that fully embraced purity culture [sexual abstinence before marriage] and rigid gender roles.” Rollins continues, “…I’d bought into the scripts offered to me by both diet culture [controlling food intake to achieve a better-looking body] and purity culture [controlling your sex drive] … [knowing] that if I controlled my appetites, I could control my world. That if I made myself smaller, I would be better, safer.”

Rollins interviewed scholars, psychologists, and an array of women while writing FAMISHED. She states, “When women worked to heal from body shame, their relationship to religion was intricately involved.”

The author divides her work into three sections: Girlhood, Marriage, and Motherhood.

GIRLHOOD

“My first obsessions were religious. My first compulsion was prayer.” Whether in church, at home, or her Christian school, Rollins had been taught to fear men’s carnal lusts—lusts she was responsible to control by negating her own desires and shrinking herself lest she cause a man to stumble into sin. At the same time, men, enshrouded with both authority and danger, were the face of God on earth.

One day, while thumbing through Delia’s, a mail-order, clothes catalog showcasing thin, scantily-clad models, a young Rollins understood that “…Delia’s sold thinness as happiness.” Kate Moss, a model popular in the early 1990s, used the following quote as a mantra: “Nothing is as good as skinny feels.” As a result, Rollins chewed pastries and donuts before spitting out the goodies into the toilet. Rollins also clearly understood her body needed to be covered in order to keep men from temptation and lust. Her reward for coloring inside those prescribed lines? A husband and a happy life.

Rollins struggles to keep her weight under 100 pounds. “…I loved to feel the high of loss.” (Oh! How I understand this.) One of her Christian schoolteachers, during chapel hour, asked the student audience, “What is it that distracts you from Christ?” She felt exposed. Her idol was not TV, money, sex, sports—the usual culprits. “I idolized my body.” Count the calories that go into it. Exercise the calories off. Any desire she ever expressed got chalked up to her inherent sinfulness known in her circles as “total depravity.” A high mark on a math test? Pride. A comfortable career path? Greed. Wanting to be attractive? Vanity. Her needs and wants were declared “deviant.” Numbing her needs, then, became the safe thing to do.

Rollins finds freedom in running so joins the school track team. Even though the school had no actual track, “I ran through the woods light and buzzing, high on fresh air and hunger. I loved when my hunger…moved from a grumbling stomach to a humming energy, despite my having never consumed anything at all. It felt like flight. It felt like power.” (There’s no better feeling in the world!)

By late high school, she realizes that “maintaining strict control over what I ate was also my way of staying in control of my emotions.” Her life atrophied as she declined social opportunities, afraid of eating in front of people, and afraid that socializing would interfere with her exercise. She writes, “I realized how much it [her life] had shrunk…and would continue to shrink.”

As Rollins considers college, she’s upset that her family’s finances dictate the necessity of attending a public university near home. “I wanted out of West Virginia, and I wanted out of fundamentalism.” Something shifted, though, once she began living on her close-to-home, secular, college campus. Here, she didn’t wonder whether she’d be “kicked out and damned to hell if my T-shirt was a bit too tight.” Her mind expanded and she “relinquished the fear that broadening my perspective was the first step toward destruction,” something her Christian, fundamentalist community taught, and for years, she believed.

Gnosticism, an early church “heresy,” taught “the body was bad, but the spirit was good.” Rollins connects Gnostic theology with her eating disorder. Desire is something to be feared, and the body is inherently bad. She longed her body to be “…reduced to nothing: to have only spirit remain.” She comes to understand her eating disorder as symbolic of her religious beliefs. “Demonization of the body is central to the evangelical purity culture….And there is significant overlap between modern-day purity culture and diet culture. Both are concerned with keeping women small. Both frame appetite as suspect. Both glory in self-denial.”

Rollins begins attending a Reformed, Protestant church that emphasized grace, and she’s relieved. In her fundamentalist upbringing, the “sinner’s prayer,” asking Jesus to forgive your sins, was an essential step towards salvation. Now she learned that the “sinner’s prayer” is a “work” and since salvation is a gift, freely given, it’s impossible (and heretical) to work for salvation Her new church taught that you are dead in your sins (total depravity) and only God gives you the desire to be saved (irresistible grace).

She also met her future husband in her “new” church’s Bible Study.

Continued tomorrow . . .

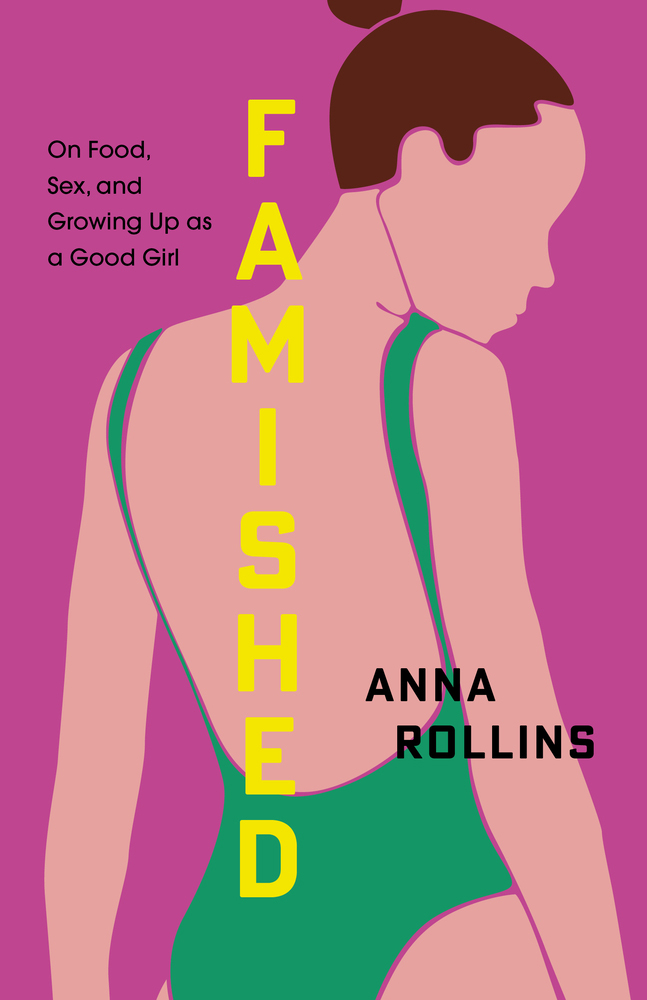

Famished can be pre-ordered at Bookshop.org here.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I wonder if any woman raised in this culture DIDN’T have a problem with food – didn’t long to be thin – I had a mother that used her scales to keep her on track – I picked up the thread – personal and cultural enculturation – both – no matter what the personal circumstances we all end up o this wheel and have to find ways to mitigate the damage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sara, for your comment. As you note, “food issues” take up a lot of space individually and collectively. Imagine if this (and other cultural problems) were not something that took such a toll of all of us! So much more creative energy would then be available to spend on things that moved us forward instead of dragging us (what seems to be) backwards.

LikeLiked by 2 people