In this sixth reflection on the life of Hafsa bint Sirin and in blogs to follow, I will be emphasizing that her much praised great piety was not incompatible with social engagement, or even sometimes a good dose of family drama.

In this sixth reflection on the life of Hafsa bint Sirin and in blogs to follow, I will be emphasizing that her much praised great piety was not incompatible with social engagement, or even sometimes a good dose of family drama.

Hafsa bint Sirin was the oldest child of freed slaves. Her parents had been taken as captives and most likely distributed as war spoils to the Prophet’s companions, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq and Anas b. Malik. Because her parents had been enslaved by such significant companions, and after their release became clients and treated like foster family, certain social advantages were open to her that might not have been for a free woman of no connection.

Let me pause here to say that there is no point in pretending, as some do, that slavery in Islam meant that the people they enslaved or clients were “like family,” in any way that makes sense to us now. The wealth of legal injunctions discussing the rights an owner had over those they enslaved makes the point. Likewise, innumerable calls to be good to enslaved people in piety literature demonstrates just how often the free had to be reminded to treat those they enslaved well. Furthermore, conversion to Islam did not mean that enslaved people were set free. I make this point because I do not want the successful story of Hafsa’s family to give the impression that Muslims who enslaved others were somehow less ethically culpable than slave owners in the Americas, nor do I want to minimize the Hafsa’s own purchase of a woman for household labour (who goes unnamed yet is also a transmitter of her story). I look at Hafsa’s story to demonstrate how women’s histories were transformed and worked for elite male purposes, this includes the histories of those who were enslaved. I address this aspect of pious women’s history in my piece on pious and mystic women in The Cambridge Companion to Sufism.

It is often said that with the coming of Islam Arab tribal social hierarchies were upended. While this is true to some degree, in practice, the social levelling that came with Islam was more of a redistribution of status than the elimination of it. Social status came in many modes and often hand in hand with great piety and great poverty. Those who sacrificed everything to join Muhammad early on and fought alongside him had the greatest rank. Those physically nearest to him or his companions had the greatest opportunity to learn about him and transmit his teachings. So even a slave of a household of one of the Prophet’s Companions would have been able to establish higher social connections based on mere proximity to these elites than a wealthy free man who lived in outside Medina.

First as enslaved servants and then clients of close companions of the Prophet, Hafsa’s parents, Sirin and Safiyya, were able to claim such connections and Sirin was eager to make use of them. Sirin had run a coppersmith business before his enslavement. He seems to have been eager to reclaim his lost status. Safiyya was the perfect wife in this regard. She was an appropriate match as a former slave, but she would also have raised him in status through her clientage relationship to the Prophet’s best friend and father-in-law, the first caliph of the Muslim community, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq. Throughout her life, Hafsa’s mother enjoyed relationships with the extended family of Abu Bakr as well as the Prophet’s wives. She was so well-esteemed, it is said that when she died three of Muhammad’s wives laid her out along with other notable companions.

The depiction of Sirin’s wedding to Safiyya bears the mark of a lavish and somewhat awkward event. He is said to have held a celebration (walima) for seven days, most likely paid for by Anas b. Malik, which would have been ostentatious by prophetic standards. Anas was a highly regarded companion, a transmitter of many hadith, but seems to have a sense of wealth that was out of keeping with some other companions of the Prophet. It is reported that Anas demanded 40,000 dirhams or more from Sirin for his freedom. Sirin could hardly afford this. He was forced to go to ʿUmar ibn al-Khattab, Muhammad’s close friend and the third caliph, for help facilitating his release. At the wedding party, the esteemed companion Ubayy b. Kaʿb stopped by, bringing other companions with him and praying for the couple. Ubayy b. Kaʿb was an early companion of the Prophet, one of his scribes and the possessor of a personal copy of the Qur’an. But notably Ubayy refused to eat at the celebration, saying he was fasting, which would have been considered a slight directed at Anas.

Despite this implied criticism, Anas held great status and was able to give Sirin and his spiritually and intellectually precocious children the best opportunities for success. Through her father and mother’s connections, Hafsa, her two sisters Umm Sulaym and Karima, and her brothers Muhammad and Yahya–not to mention her half-siblings, some of whom also transmitted hadith–would have grown up in the deeply intertwined social, scholarly, and devotional circles of the Companions and Followers in Medina and Basra. Because her family had access to these elite social circles, Hafsa had the opportunity to memorize the Qur’an by the age of twelve as well as sit with companions such as Umm ʿAtiyya, Abu al-ʿAliya, and Salman b. ʿAmir from whom she transmits hadith. Ultimately, she became known as a reliable scholar and a woman of great piety and was taken seriously in influential circles (as we saw when she argued the legal status of women’s right to pray the ʿeid prayer at the mosque).

Later Anas contracted a second marriage for Sirin to one of his former slaves, then, again decades later, to one of his nieces as a third or fourth wife, thus elevating Sirin from client to family. Given Sirin’s multiple marriages, Hafsa grew up around many siblings in what was likely to have been a bustling compound of rooms. Her father tried to make space for his children’s devotional needs. It is said that he built separate prayer spaces of wooden planks for her, Muhammad, and Yahya. But such quiet spaces devoted to piety did not keep Hafsa from family drama arising from Sirin’s marriages.

When Anas offered Sirin his niece in marriage, Hafsa was supportive of the match despite her mother’s clear objection. Hafsa may very well have accepted the multiple marriages. She may have felt some advantage to them given her close relationships with her siblings and the social ties it further afforded them. Marriage was primarily a social arrangement for families, not solely a matter of legitimating desire or love. Or she may simply be portrayed this way to promote what male transmitters would consider a proper pious response highlighted against that of her mother. Whichever the case, it is reported that when given the news, she congratulated her father for a tie that would raise them from a clientage relationship to family with Anas. But when Hafsa delivered the news to her mother, Safiyyah insulted Hafsa for supporting her father and retorted, “Tell your father, ‘May you be distant from God!”’

To be continued…

(Accounts are taken from Ibn Saʿd’s Tabaqat al-kubra, her transmissions of hadith, and Ibn al-Jawzi’s Sifat al-safwa). Thanks goes to Yasmin Amin for clearing up a few matters, including the nature of Safiyya’s message to Hafsa’s father [literally, may God keep you young, but meaning, may you be delayed in meeting God and so distant from God]).

Laury Silvers is a North American Muslim novelist, retired academic and activist. She is a visiting research fellow at the University of Toronto for the Department for the Study of Religion. Her historical mystery series, The Lover: A Sufi Mystery, is available on Amazon (and Ingram for bookstores). Her non-fiction work centres on Sufism in Early Islam, as well as women’s religious authority and theological concerns in North American Islam. See her website for more on her fiction and non-fiction work.

On CNN’s

On CNN’s

At times, being ignored, erased, and made invisible, is more hurtful than open debate and disagreement. Such silencing and marginalization render the energy, activism, and work of so many people mute and, ultimately, they do not serve the communities and society we are attempting to change. In what follows I insist on uplifting and naming some of the radical Muslim activists and advocates for gender justice I saw ignored in a recent Muslim community event.

At times, being ignored, erased, and made invisible, is more hurtful than open debate and disagreement. Such silencing and marginalization render the energy, activism, and work of so many people mute and, ultimately, they do not serve the communities and society we are attempting to change. In what follows I insist on uplifting and naming some of the radical Muslim activists and advocates for gender justice I saw ignored in a recent Muslim community event.

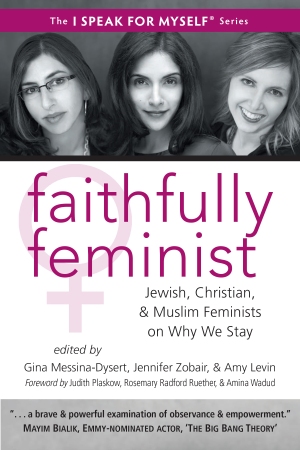

Kecia Ali, one of the contributors to this Feminism and Religion blog, recently wrote an excellent article titled, “

Kecia Ali, one of the contributors to this Feminism and Religion blog, recently wrote an excellent article titled, “