In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest in Lancashire, Northern England were executed at Lancaster Castle.

In 1612, in one of the most meticulously documented witch trials in English history, seven women and two men from Pendle Forest in Lancashire, Northern England were executed at Lancaster Castle.

In court clerk Thomas Potts’s account of the proceedings, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, published in 1613, he pays particular attention to the one alleged witch who escaped justice by dying in prison before she could come to trial. She was Elizabeth Southerns, more commonly known by her nickname, Old Demdike. According to Potts, she was the ringleader, the one who initiated all the others into witchcraft. This is how Potts describes her:

She was a very old woman, about the age of Foure-score yeares, and had been a Witch for fiftie yeares. Shee dwelt in the Forrest of Pendle, a vast place, fitte for her profession: What shee committed in her time, no man knows. . . . Shee was a generall agent for the Devill in all these partes: no man escaped her, or her Furies.

Quite impressive for an eighty-year-old lady!

In England, unlike Scotland and Continental Europe, the law forbade the use of torture to extract witchcraft confessions. Thus the trial transcripts supposedly reveal Elizabeth Southerns’s voluntary confession, although her words might have been manipulated or altered by the magistrate and scribe. What’s interesting, if the trial transcripts can be believed, is that she freely confessed to being a healer and magical practitioner. Local farmers called on her to cure their children and their cattle. She described in rich detail how she first met her familiar spirit, Tibb, at the stone quarry near Newchurch in Pendle. He appeared to her at daylight gate—twilight in the local dialect—in the form of beautiful young man, his coat half black and half brown, and he promised to teach her all she needed to know about magic.

Tibb was not the “devil in disguise.” The devil, as such, appeared to be a minor figure in British witchcraft. It was the familiar spirit who took centre stage: this was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form, as Emma Wilby explains in her excellent scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Mother Demdike describes Tibb appearing to her at different times in human form or in animal form. He could take the shape of a hare, a black cat, or a brown dog. It appeared that in traditional English folk magic, no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their spirit familiar—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Belief in magic and the spirit world was absolutely mainstream in the 16th and 17th centuries. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in spells and witchcraft—rich and educated people believed in magic just as strongly. Dr. John Dee, conjuror to Elizabeth I, was a brilliant mathematician and cartographer as well as an alchemist and ceremonial magician. In Dee’s England, more people relied on cunning folk for healing than on physicians.

As Owen Davies explains in his book, Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History, cunning men and women used charms to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was technically illegal—sorcery was a hanging crime—but few were arrested for it as the demand for their services was so great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbs and charms was far less likely to kill you.

In this period there were magical practitioners in every community. Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches.

But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods can turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. This is what happened to 16th century Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop of Edinburgh, cited by Emma Wilby in Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits. Dunlop was burned as a witch in 1576 after her “white magic” offended the wrong person.

Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder. If your neighbours turned against you and decided you were a witch, you were doomed.

Although King James I, author of the witch-hunting handbook Daemonologie, believed that witches had made a pact with the devil, there’s no actual evidence to suggest that witches or cunning folk took part in any diabolical cult. Anthropologist Margaret Murray, in her book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921, tried to prove that alleged witches were part of a Pagan religion that somehow survived for centuries after the Christian conversion. Most modern academics have rejected Murray’s hypothesis as unlikely. Indeed, lingering belief in an organised Pagan religion is very difficult to substantiate. So what did cunning folk like Old Demdike believe in?

Some of her family’s charms and spells were recorded in the trial transcripts and they reveal absolutely no evidence of devil worship, but instead use the ecclesiastical language of the Catholic Church, the old religion driven underground by the English Reformation. Her charm to cure a bewitched person, cited by the prosecution as evidence of diabolical sorcery, is, in fact, a moving and poetic depiction of the passion of Christ, as witnessed by the Virgin Mary. The text, in places, is very similar to the White Pater Noster, an Elizabethan prayer charm which Eamon Duffy discusses in his landmark book, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580.

It appears that Mother Demdike was a practitioner of the kind of quasi-Catholic folk magic that would have been commonplace before the Reformation. The pre-Reformation Church embraced many practises that seemed magical and mystical. People used holy water and communion bread for healing. They went on pilgrimages, left offerings at holy wells, and prayed to the saints for intercession. Some practises, such as the blessing of the wells and fields, may indeed have Pagan origins. Indeed, looking at pre-Reformation folk magic, it is very hard to untangle the strands of Catholicism from the remnants of Pagan belief, which had become so tightly interwoven.

Unfortunately Mother Demdike had the misfortune to live in a place and time when Catholicism was conflated with witchcraft. Even Reginald Scot, one of the most enlightened men of his age, believed the act of transubstantiation, the point in the Catholic Mass where it is believed that the host becomes the body and blood of Christ, was an act of sorcery. In a 1645 pamphlet by Edward Fleetwood entitled A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderfull Monster, describing how a royalist woman in Lancashire supposedly gave birth to a headless baby, Lancashire is described thusly: “No part of England hath so many witches, none fuller of Papists.” Keith Thomas’s social history Religion and the Decline of Magic is an excellent study on how the Reformation literally took the magic out of Christianity.

However, it would be an oversimplification to state that Mother Demdike was merely a misunderstood practitioner of Catholic folk magic. Her description of her decades-long partnership with her spirit Tibb seems to draw on something outside the boundaries of Christianity.

Although it is difficult to prove that witches and cunning folk in early modern Britain worshipped Pagan deities, the so-called fairy faith, the enduring belief in fairies and elves, is well documented. In his 1677 book The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. The Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop mentioned earlier, while being tried for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit was a fairy man sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame.

A 17th century woodcut depicting a petitioner approaching the fairies in their hollow hill.

Mary Sharratt is an American author living in Pendle Witch country in northern England, the dramatic setting for her novel, Daughters of the Witching Hill, based on the true story of the folk healer and wisewoman, Elizabeth Southerns and her family. Mary is also the author of Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen. Visit her website.

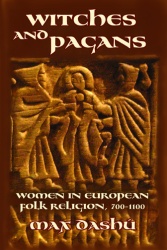

Max Dashu’s

Max Dashu’s  Pelišky was one of the first movies I watched in the Czech Republic. It takes place in the year (maybe years) before the Soviet Occupation. It follows the lives and struggles of ordinary families. One of the best and funniest scenes takes place at a small post-wedding dinner. The couple receives some new-fangled plastic spoons as a wedding present. The gift-giver is very proud of the fact that they were made in Eastern Germany. One of the characters stirs her tea with the spoon and is about to lick it but as she takes it out of the hot tea it bends as if it was made of rubber. Soon the scene dissolves into arguments, frustrations and disappointments.

Pelišky was one of the first movies I watched in the Czech Republic. It takes place in the year (maybe years) before the Soviet Occupation. It follows the lives and struggles of ordinary families. One of the best and funniest scenes takes place at a small post-wedding dinner. The couple receives some new-fangled plastic spoons as a wedding present. The gift-giver is very proud of the fact that they were made in Eastern Germany. One of the characters stirs her tea with the spoon and is about to lick it but as she takes it out of the hot tea it bends as if it was made of rubber. Soon the scene dissolves into arguments, frustrations and disappointments.