A story that follows on from my version of Perseus and Medusa…

Perseus flew on, away from Medusa. He gave thanks to Athene that he had understood her words, “It is necessary that I have the head of Medusa. Therefore I bid you seek her out”, just in time to avoid a killing.

He flew across the sea until he reached a rocky coastline, the boundary of a fertile kingdom. Here he landed and was given hospitality by the king and queen. Though they made him a welcome guest he could see that they were greatly upset and he asked why. He learnt that they had offended the Changeless Changeable Ones, the Goddesses of the Sea. They had sent out a sea-serpent and demanded that the princess Andromeda be given to the monster. The king and queen begged Perseus, who they could see was a hero, to aid them and he agreed.

Next morning Andromeda was taken to the seashore and chained to a rock. She asked them not to chain her, saying that it was not necessary and that the monster was her fate. But they were afraid she would run away and bring a worse disaster on the land, and they would not listen to her.

Perseus leapt lightly into the air on his winged sandals, while the king and queen and all the people retired to the safety of a cliff-top. Perseus looked at Andromeda as he waited for the monster – as she stood there so calmly the tall grey-eyed young woman seemed to him like a mortal image of Athene. He looked out to sea where great waves were coming in as the monster approached. The monster in some way reminded him of the Gorgon. He waited for the monster to come closer. The people on the cliff-top were cheering madly at the sight of him, encouraging him while he waited.

He continued to wait while the sea-beast came closer and closer. His mind whirled as he looked, now out to sea, now back to the shore. Andromeda… Athene… the monster… Medusa… Andromeda… the monster… Athene… Medusa. As the monster neared the shore he drew his sword. The crowds on the cliff-top were calling even more wildly now, yelling “Strike”, “Save the princess”, “Kill the monster” and other encouragements. He raised his sword and struck downwards swiftly and accurately.

The sword cut keenly through the chains binding Andromeda. She walked calmly across to the waiting beast, stroked it, climbed onto its back, and the two sped out to sea and were soon lost to sight. Before she left she gave Perseus a smile of thanks.

But he realised that the thanks were due from him to her. She had known that the monster was her destined ally who would help her find the freedom she sought. She could simply have waited for the monster to break the chains, but she chose to give Perseus the opportunity to make a good decision. He was glad she was prepared to trust in him and wondered what would have happened if he had killed the monster. Perhaps Andromeda, whose name – which meant ‘ruler of men’ – suggested her destiny, would have become bound to him by invisible chains more imprisoning than those he had cut. Perhaps she would be known only as “the rescued princess” or “the wife of Perseus”, and not recognised as a person in her own right. Perhaps he would have come to seem to her, and even to be, more frightening than any monster, a cruel being who could only destroy, not create.

(Notes) This follows on from my version of Perseusand Medusa, which is too long for this blog.

The name Andromeda does mean ‘ruler of men’. The story of Perseus, Andromeda, and the monster from the sea later became the story of St. George and the dragon (they even took place in the same town!). This is one of the stories that feminists have had most fun in rewriting; for instance, Perseus and Andromeda in Suniti Namjoshi’s Feminist Fables and a retelling, on a British radio program, by Jenjoy Silverbirch. Also, on a poster for a fund-raising event, and in the Goddess issue, which they produced, of Shrew magazine, the Matriarchy Study Group, one of the first Goddess groups in Great Britain, showed a “Maiden escaping from Saint George with the aid of a friendly dragon”.

In Christian times, the dragon has been seen as a symbol of evil. However, ‘dragon’ comes from a Greek word meaning ‘to see clearly’, so perhaps dragons are originally oracular beasts.

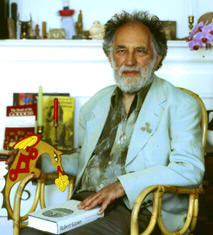

Daniel Cohen has been active in the Goddess movement in Great Britain for many years, and was co-editor of “Wood and Water”, a Goddess-centred, feminist-influenced pagan magazine which ran for over twenty years. He is particularly interested in how Goddess spirituality can open up new ways of behaviour for men, non-oppressive and using their talents to heal rather than harm. He believes that myths and old stories have great power to shape behaviour, and so a valuable tool for change is to find new stories or to tell old stories in new ways. This story is one of his many re-tellings and re-visions. An illustrated collection of twenty-five stories has recently been published under the title “The Labyrinth of the Heart” (ISBN 978-0-9513851-2-8), and can be ordered from both physical and online bookstores. Some of the stories, together with book reviews, articles, and poems, can be found on his website at http://www.decohen.com

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I love your stories! I think they need retelling and recasting. I’ve been doing that with fairy tales for several years. I hope you’ll give us another of your stories next time.

LikeLike