Cinderella helped make me a pint-sized feminist. Well, of course my strong and rebellious mother and grandmothers were my primary influences, but at age five, Cinderella was definitely up there. I learned in my own little girl way from Disney’s Cinderella that women could forge their own destiny (of sorts), older women can be powerful for good and evil, magic pervades the universe, and whether other women support you is key to success. I completely missed the message about marrying Prince Charming. How did this story get from its origins millennia ago to a little suburban American girl in the 1960s?

Once upon a time, all over the globe, women practiced the inspiring, transformative art of storytelling. In Europe, as their world was overtaken by more patriarchal cultures, they kept alive fairy tales that spoke of their traditional world infused with magical energy and spirit beings and shared with each other new tales of their lives and troubles. In many western cultures from ancient times till very recently, however, storytelling was strictly segregated by gender, with men gathering in taverns or homes to hear epic hero tales while women gathered to sing or tell stories to each other of supernatural beings, local events, and their lives while doing tasks like spinning (hence, “spinning a yarn”) and weaving. Not surprisingly, male folklore scholars have for decades overlooked women storytellers who were also often devalued and denigrated in their own communities. More recently, largely female folklore scholars have brought to light a rich and important tradition of European women storytellers.

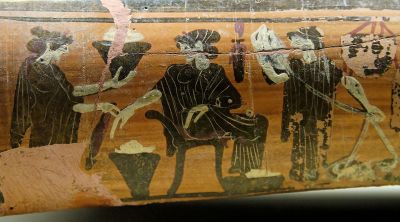

As far back as ancient Greece and Rome, while some women poets and storytellers were well known, much storytelling happened as women were spinning and weaving cloth together, secluded in their homes. The poet Tibullus writes “But I pray that you remain faithful, and that an old woman sit at your side.. She can tell you stories and by lamplight spin out long threads from a full distaff” (Heath, 76). Women, like Helen in the Iliad, also wove stories into cloth, either their own or myths resembling their plight. Ancient texts tell us that these women told the same “traditional tales of heroes, gods, and love” (Heath, 81), and heroines and goddesses, as well-known male poets, but were especially known for tales related to the afterlife, miracles, and the supernatural.

In Ireland, one Irish woman interviewed in the 1980s by Clodagh Brennan Harvey, said that women did not tell stories as much as men because “we had to be at home baking bread for the next day” (Harvey, 114). And furthermore, telling epic tales was unladylike. One woman’s grandmother said “You’d be making a tomboy of yourself by telling them stories” (Harvey, 120). Yet the first woman admitted “we’d steal out very often by night and go into some house where there’d be no man inside — a woman. And they were great for telling stories about fairies…or stories about priests and other local happenings…” (Harvey, 114).

Aida Vidan found evidence in material collected in what is now Bosnia in the 1930s that it was common, again, for one or two women to sing “shorter lyric songs, humorous songs of various length, and longer narrative ballads” (Vidan, 12) to each other while gathered doing housework. The song stories often somberly focused on troublesome relationships while others were the same epic stories sung by men but from a woman’s viewpoint.

While derided as “old wives tales” by some male storytellers, the fairy stories women told were deeply powerful, which may be why the stories and storytellers were so denigrated. Often the stories the female scholars collected were about the hard and stark truths of the women’s lives, including some that were original. Kathleen Vejvoda recounts a tale told by an Irish recent widow in her 60s of how she was once strong and beautiful, but one night not long before a “pooka” violently attacked her causing her to have a “crookened” back. The storyteller’s language evokes feelings of violence and violation and a deep feeling of loss at her sudden transformation from a cherished wife to a devalued elderly widow. This accords with recent scholarship that finds that “fairy lore helped individuals and the community to account for psychological states such as depression and anger, or social conditions such as marginalization and alienation” (Vejvoda, 45).

As Patricia Monaghan once noted, ancient stories of spirit beings, such as those told by women storytellers, can also contain important truths that those in power may not wish to hear. She retells one story of a magic cow that gave unlimited amounts of milk until someone tried to milk her into a sieve that would never fill, causing her to leave Ireland to starve. The message about not exploiting our natural world is clear and very contrary to those who would use the Earth and its living beings for personal gain.

Fairy stories could also be a way of keeping alive the memory of stories of elemental beings and a worldview from a time when women had more status. The world they recreated with words had not only pookas, but also Fairy Queens and other powerful female spirit beings long since banished by patriarchal institutions. Could this be why in Ireland women storytellers were told that the beings themselves would attack the women for telling stories about them? One Irish woman storyteller told Victorian folklore collector Lady Gregory that she was being punished by the fairies for telling stories when her walking stick accidentally burned in the hearth fire (Vejvoda, 50).

Women’s telling of fairy or mythic stories to their children, reported in Ireland, Bosnia, and ancient Greece and Rome, also transmitted both the stories and messages they carried to the next generation, an essential cultural task. While we may have favorite stories learned later in life, it is the stories from childhood that form the basis of our first life perspective.

The stories these women told were powerful, and they were able to bring their stories through the centuries, generation to generation, keeping them for us even if in greatly altered, more patriarchal forms. When I was five, Disney’s Cinderella was the best I had for ancient fairy tales of strong mortal and spirit women showing me how to navigate life’s challenges, such as it was. Today’s young women have both myriad books and a new generation of feminist storytellers to entertain and inspire them. Just as we stand on their foundation to carry on their work in new and exciting ways, may the stories we tell also encourage and teach each other, our daughters, and our granddaughters.

Sources:

Harvey, Clodagh Brennan. “Some Irish Women Storytellers and Reflections on the Role of Women in the Storytelling Tradition.” Western Folklore. Apr., 1989, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 109-128.

Heath, John. “Women’s Work: Female Transmission of Mythical Narrative.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014). Spring 2011, Vol. 141, No. 1 (Spring 2011), pp. 69-104.

Lord, Albert Bates. The Singer of Tales. 2000. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2000, http:/nrs.harvard.eduurn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_LordA.The_Singer_of_Tales.

Messenger, John. “Joe O’Donnell, ‘Seanchai’ of Aran.” Journal of the Folklore Institute. Dec., 1964, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Dec., 1964), pp. 197- 213.

Monaghan, Patricia. “Calamity Meat and Cows of Abundance: Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Irish Folklore.” Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. Vol. 19, No. 2, Thematic Focus: Human Ecology and the Anthropology of Place (2010), pp. 44-61.

Vejvoda, Kathleen. ”Too Much Knowledge of the Other World”: Women and Nineteenth-Century Irish Folktales.” Victorian Literature and Culture. Vol. 32, No. 1 (2004), pp. 41-61.

Vidan, Aida. Embroidered with Gold, Strung with Pearls: The Traditional Ballads of Bosnian Women. 2003. Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature 1. Cambridge, MA: Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_VidanA.Embroidered_with_Gold_Strung_with_Pearls.2003.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I do agree on the importance of listening to our storytellers – psychologically they help us in ways beneath everyday awareness by clarifying direction, exposing patterns, and by using imagination to feel our way beyond what we think we know – and they also used to keep Nature Animate on some level – But somehow we have lost the link between the stories and the truths they tell and manifesting these truths/beliefs on the outside – Nature still shows me that magic is real, but I lose that sense the moment I am interacting with the culture at large.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right. It can be so hard to maintain that link when we live in a world that denies it. I find it fascinating, though, that it seems that these groups of women and the stories they told were able to keep that link among themselves for so long. I think the stories they told themselves and each other touched on the deep power of the beings they spoke about, like the pooka as well as figures like Frau Holde (the original of Mother Goose, I believe), the Cailleach, and other beings that had such connections to nature and its wildness. Now that these stories are being told more, I hope that we, too are able to find that connection to nature through them at times, even though it is so hard.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“In Europe, as their world was overtaken by more patriarchal cultures, they [women storytellers] kept alive fairy tales that spoke of their traditional world infused with magical energy and spirit beings and shared with each other new tales of their lives and troubles.” I agree wholeheartedly, Carolyn. But unfortunately, as the male story collectors, like the brothers Grimm, collected these stories, they reduced their woman-positive qualities. For instance, there are studies that show that the earlier collections by Grimm held more quotations by women characters, but in later collections, even women’s words were reduced. When the gatekeepers of culture are solely male, women get lost, reduced, or shunted aside. That’s why it’s so important for us to support women’s voices.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s so true! I imagine that the “fairy tales” that came down through the male writers who put them into books are quite different from the ones that women told around spinning wheels to each other. We get a glimpse of some of them through stories like “The Crookened Back” that come directly from the women themselves, but I noticed how often the women scholars who found the women storytellers, or at least signs of them in texts or previously collected materials said “what WERE the stories these women told each other when they were alone, when there were no men to hear?” And, of course, tales that come down through the oral tradition have a life and dynamism of their own that stories written down don’t have. Thanks for letting us know about the studies of the Grimm tales, which say so much about the stories that we heard and how they were changed.

LikeLike

I didn’t know or remember that Frau Holde was the original mother goose – but I have a thing about geese – and feed them regularly! They are adorable – some manifestation of the ancient goddess – I absolutely believe that the geese helped me get back from New Mexico safely the year of the pandemic… long story that one. – All of these stories return us to nature – highlighting the wisdom to be found there – problem is today – who but feminists are paying attention? They have barbie and robots instead….My hope is that some will reclaim what has been buried before it’s too late –

LikeLike

I agree that it is too bad that we don’t know the stories the women told when men weren’t around. My great-grandmother was great at making up stories on the spur of the moment for my mother and her twin. My grandmother tried to get her to write them down, or let my grandmother record them, but my great-grandmother wouldn’t let her. She didn’t think her ability to make up stories on the spot was remarkable. I sure wish I had her talent!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder if this ability to make up stories on the spot is a remnant of the oral tradition where people would have many, many stories in their memory that they could draw on for themes, characters, etc. The sense I get from reading these articles about the storytellers is that there is at least some sense of what we have lost by relying too heavily on written sources – a sense of community as people sat around telling stories, the understanding that stories can be fluid and respond to what is currently happening, not just be what one writer wrote at one time, the sharing of the ability to tell stories and not relying on professional writers, etc. I remember one circle I went to where we all made up a story together as part of a solstice ritual and it was not only fun, but magical. Maybe we need to do more of that kind of thing! And I bet you do have your great-grandmother’s talent – maybe all we of our generation need is some practice in making up stories!

LikeLike

I think you’re right that we just need practice making up stories, Carolyn. I’ll bet my great-grandmother’s stories were a remnant of the oral tradition. She was Canadian of English and Welsh ancestry. My grandmother wrote poems and songs. I found a couple of them in her old tea cart, which I now have. I always wanted to be a writer but I wanted a steady paycheck so I became a newspaper reporter. I love your idea of a group making up a story! Maybe the women in my singing circle can do that on our next retreat. I’ll have to suggest it. Blessings.

LikeLiked by 1 person