This was originally posted on November 29, 2015

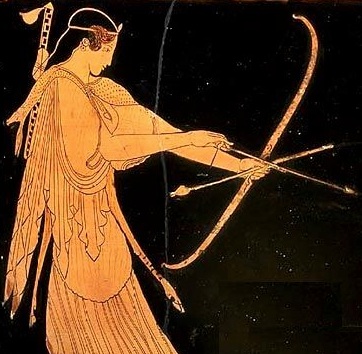

The 2015 Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded in part to a Chinese woman (Tu) for her identification and isolation to treat malaria of a chemical known as Artemisinin. The name of that chemical derives from the fact that it is found in varying amounts in the ‘family’ (technically, genus) of plants known as Artemisia. The name of that family derives from its association with the goddess Artemis.

Because Tu’s work began in China in the 1960s it is understandable that even if she knew this about Artemisia (a term I use to refer to any one plant or all of the plants of that family) it would not have been a ‘careerbuilder’ for her to point it out to those for whom she was working. It was bad enough that she was a woman. At that place and time, however, if she had said or done something that could be associated with Western culture her name might not even be known today.

Nevertheless, because those awarding the Nobel Prize are free from discrimination or intimidation, it is startling that in the explanation provided for the award no mention is made of the Western legacy of Artemisia. To begin with, the very fact that the Prize was being awarded to a woman for a plant named after a goddess should have elicited at a sense of uncanniness that arguably deserved mention. Be that as it may, the failure to mention that Artemisia has a long history of being used medicinally in the West not only as an insect repellent but also to treat fever–a common symptom of malaria–is simply inexcusable.

It is, however, not surprising. Notwithstanding that Artemisia was thought of in the ancient Hellenized world as a panacea, there should be little doubt that its relationship to Artemis and its use by women to treat health issues unique to women contributed to its marginalization and neglect by a medical profession dominated by men. The historical (and modern anecdotal) evidence would otherwise have attracted far more scientific scrutiny than it has to date. For it seems Artemisia, inter alia, (1) ameliorates symptoms related to menstruation and its cessation, (2) prevents conception, (3) induces abortion and (4) prevents, impedes or reverses the growth of cancer cells, especially breast cancer cells.

Moreover, thousands of years of usage–the ultimate ‘lab test’ Darwin particularly prized–both medicinally and for culinary purposes indicate there to be no substantive risks in doing so. Indeed, the very fact that Artemisia is virtually ubiquitous in the Northern hemisphere suggests that at a very early stage in human evolution women took its seeds with them wherever they went. Ironically, Artemisia’s very ubiquity is another contributing factor to what looks suspiciously like willful ignorance about it. For if modern science were to confirm the efficacy to which its traditional medicinal usage attests, then it would mean that those profiteering off of its more expensive and more risky alternatives would be out of business. Yet, if Artemisia is as efficacious as it seems to be, its ubiquity ultimately will render moot debates about whether, when or how women manage what are essentially symptoms of being a woman.

Because its ubiquity is evidence of the antiquity of Artemisia it is fair to assume it would have been known to Sappho. Although there is no reference to Artemisia in her poetry, a relatively long fragment focuses on Artemis (S. 44(A)(a)). It constitutes not only one of the earliest references to her but it is the only such reference in ancient literature that can be attributed to a woman and hence is uniquely authoritative.

After narrating how Artemis came to be called the “Virgin Deerhunter,” Sappho adds, “Eros never comes near her.” Though the fragment breaks off at that point, it seems to mean she thought of Artemis as having a force field around her. It is tempting to compare this to how one type of magnetic or electrical charge repels, rather than attracts, another of the same type. It appears, though, that Sappho had the force of a chemical reaction in mind, a reaction primarily detected by taste.

Sappho appeals to the sense of taste in characterizing Eros in another fragment as “bittersweet” (S. 130). While she refers to him with a word commonly translated ‘creature’ it could mean ‘insect’–a meaning consistent with how Eros was thought of in antiquity (most familiar today as Cupid of the Latin tradition). Because a flying insect such as a mosquito is directly experienced in being bitten by it, Sappho’s association of how Eros, as such an insect, ‘tastes’ to one bitten by him curiously combines myth and fact.

Given that context two facts become surprisingly relevant: Artemisia is an effective insect repellent and most types taste bitter. Therefore, Sappho had a factual basis for believing the plant Artemisia actually to be Artemis (she may have used the names interchangeably) because of the effect its bitterness had on Eros as an insect. Perhaps she tasted something of a homeopathic principle at work, with the ‘bitter’ of the bittersweet sting of the insect cancelled by the bitterness of the plant (cf. the magnetic or electrical charge analogy).

Precisely what type of Artemisia was known to Sappho and what type of insect she associated with Eros cannot be determined. Yet, not only is precision not necessarily applicable to the interpretation of poetry, but it is not, as a matter of scientific procedure, even logical (as Charles Peirce aptly noted). Especially where evidence is wanting, precision rather than generality or even vagueness risks cutting off in advance (praecidere) the relevant possibilities of what actually may prove to be true.

It is possible the ‘Eros’ insect for Sappho was the gadfly, oistros in Greek, the Latinized form of which was used to name the female hormone estrogen. That name was coined by ‘scientific’ men out drinking at a London pub in the 1930s (a “happy thought” as one of them put it). The only thing ‘happy’ about that thought–which implies a diagnosis of menstruation as a type of monthly malaria (and even madness)–is how it now can be related to S. 44(A)(a). For some attribute Artemisia’s effectiveness in certain cases to its ability selectively to target estrogen dependent chemical processes. Therefore, it would seem that what Sappho tasted as a mythological drama–a ‘Hunger Game’ between ‘bitter’ enemies–is in fact being played out on a molecular level when Artemis as Artemisia enters a woman’s bloodstream.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “From the Archives: Artemis As Artemisia: Ancient Female Spirituality & Modern Medicine by Stuart Dean”