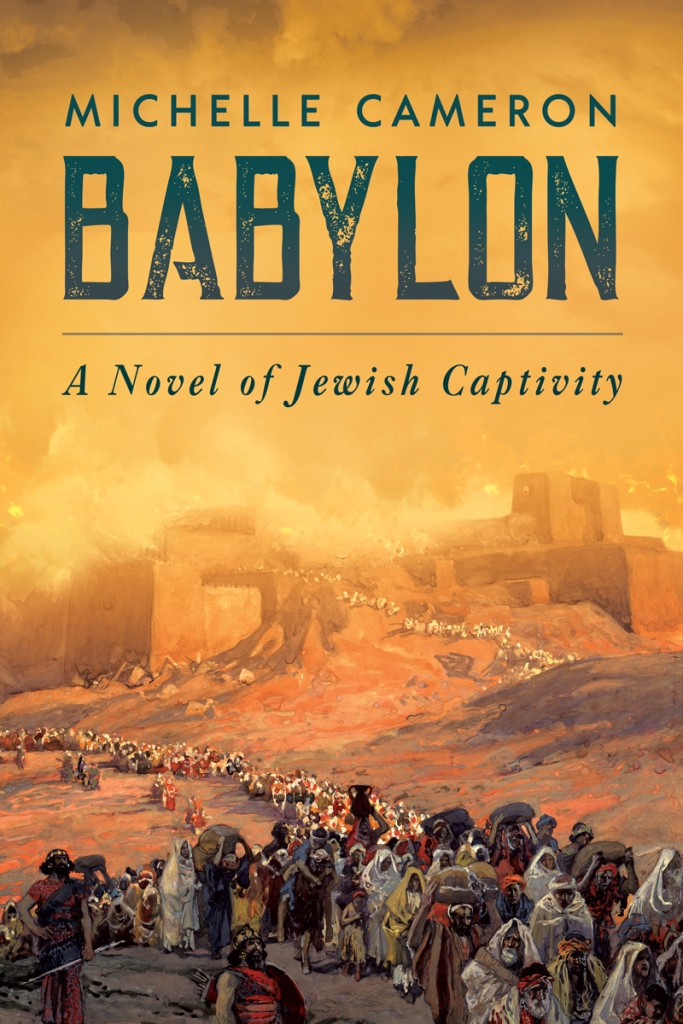

When one nation conquered another in antiquity, vanquished peoples typically switched allegiances to that country’s gods, since those deities were clearly stronger than their own. In my novel, Babylon: A Novel of Jewish Captivity, the prophet Daniel warns against this tendency, so the Judean exiles would remain faithful despite their captivity:

“You may be tempted to slip away from your Hebrew roots. Many of us struggle to remain steadfast to our faith. We are seduced by the lure of the gods of Ishtar and Marduk, Sin, Damkina, and Ea. Their temples overflow with riches and their ways are strange and compelling.

“But I urge you to remember the promise the Almighty gave Abraham in the desert not far from here: That we will be a prosperous people residing in our own land. We do not despair of a Return, a rescue from exile not unlike the one we were favored with during the days of Moses.” (Babylon, Chapter 10, “Seraf and Daniel”)

Yet it didn’t take banishment to encourage the Judeans to worship other deities. The sages note that God engineered the exile for exactly that reason – because the people mixed their worship of God with that of others. The prophet Jeremiah railed against these practices:

“Seest thou not what they do in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? Children gather wood, fathers light the fire, and women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven.“ (Jeremiah 7:17)

The women of Judea worshipped Asherah, borrowing from the Canaanite mythical fertility goddess who, together with El, birthed seventy gods. The Judeans erected poles as totems of worship next to God’s altars, raising the prohibition in Deuteronomy 16:27: “You must never set up a wooden Asherah pole beside the altar you build for the Lord your God.”

But one of the defining characteristics of the Judean exile was the loss of the Temple, so the exiles had to find new modes of worship. These included transcribing Biblical stories and private prayer. Babylon describes Daniel praying three times a day:

Daniel knelt by his open window, hands on the sill, eyes resting on the vast reaches of desert that separated him and the lost city of Jerusalem. A slight breeze bathed his face in its damp coolness. Seraf, staring, recognized a peace residing within the exiled seer that Seraf had deemed lost forever. (Babylon, Chapter 18, “Daniel at Prayer”)

But such activities did little for the Judean women, whose focus was naturally domestic. And so, in a land where the goddess Ishtar was paramount, they reverted to baking Goddess cakes, as in this scene where young Chava is taught to pour the batter:

Zakiti smiled. She was proud of her skill in creating the mystical crescent shape. As soon as the cake began to bake, she took a peeled stick and carved the lush image of a woman into the thickening batter.

“She certainly looks fertile enough,” Mirav commented, nodding approvingly.

“When will I look like that?” Chava pointed to her flat chest. “Like my cousins?”

The women laughed. “When you’re a little older than seven,” Mirav told her daughter. “I promise, in a few years from now the Goddess will give you a woman’s curves.”

Zakiti invoked part of the prayer as she completed the drawing. “Let the favor of thine eyes be upon me, oh Ishtar. With thy bright features, look faithfully upon me. Drive away the evil spells of my body and let me see thy bright light.” (Babylon, Chapter 37, “The Queen of Heaven Cakes”)

This mixing of deities from many countries was common in ancient times, when people of diverse faiths lived in close proximity. Seven-year-old Chava, however, is confused:

“You said Ishtar,” Chava said, watching as the cake puffed around the shape etched into it. “Is Ishtar the Goddess of Heaven?”

“She has many names. We Judeans call her Asherah,” Mirav explained. “It’s your aunt who calls her Ishtar because that’s what they call her here in Babylon. But she’s a secret for women only. Don’t tell your father.” (Babylon, Chapter 37, “The Queen of Heaven Cakes”)

This warning is prophetic, as Chava’s father and uncle burst in and trample the cakes underfoot:

“How dare you!” Mirav screeched. “It took us all morning to get the stones hot enough.”

“And what did I tell you last time about these cakes?” Nachum yelled just as loudly. “Zakiti has an excuse, perhaps—the customs of her youth mislead her. But you, Mirav, daughter of Judea—you should know better. You disgrace us by baking in sacrifice to your false Goddess!”

Zakiti glared at him. False Goddess, indeed!

Mirav put her hands on her hips. “My mother back in Judea made Goddess cakes! My father always laughed at her, but he ate more of them than anyone. And we live in Babylon now, not Judea. Why shouldn’t I sacrifice to the Goddess?” (Babylon, Chapter 37, “The Queen of Heaven Cakes”)

Chava’s uncle, Uri the scribe, then recalls Jeremiah’s warnings:

“Yes, the women of Judea worshipped the Goddess. Jeremiah said such practices angered God. It is why God broke his covenant with us. If we wish for a Return to our homeland, we must vigilantly avoid practices such as Goddess sacrifice.” (Babylon, Chapter 37, “The Queen of Heaven Cakes”)

After another angry exchange with the women, he continued:

“Jeremiah himself could not sway the minds of the people and could not persuade them not to bake their cakes. Like you, sister, they protested that they would always sacrifice to the Queen of Heaven. They pledged themselves to continue to pour drinks to the goddess and burn incense to her—all because their mothers and grandmothers had taught them to do so.” (Babylon, Chapter 37, “The Queen of Heaven Cakes”)

As the author, despite not taking the scene further, I expect that goddess cakes would continue to be made – in secret, when the men aren’t around. Because, of course, both back then as now, women needed ways to express their specific needs – ways generally not taken into account by male modes of worship.

BIO: Michelle Cameron is the author of Jewish historical fiction, with her most recent being Babylon: A Novel of Jewish Captivity. Previous work includes the award-winning Beyond the Ghetto Gates and The Fruit of Her Hands: the story of Shira of Ashkenaz. She has also published a verse novel, In the Shadow of the Globe. Napoleon’s Mirage, the sequel to Beyond the Ghetto Gates, is forthcoming in August 2024.

Michelle is a director of The Writers Circle, a NJ-based creative writing program serving children, teens, and adults. She lives in Chatham, NJ, with her husband and has two grown sons of whom she is inordinately proud.

Website: https://michelle-cameron.com

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hebrews originally came from Canaan. Joseph and his family were Canaanites. The Rabbi I spoke to once told me, that the word Hebrew comes from Habiru or Hapiru (River crosser) a term for a Canaanite immigrant. Basically, border jumper. So the Canaanite religion is the traditional religion of the Hebrews. The idea of Monotheism was actually imposed on them in Persia due to the influence of Zoroastrianism. That’s why Semitic Polytheism or Paganism whatever you wanna call it, exists even today. I’m only a novice in Semitic Polytheism but El (One of Adonai’s many names) is the Supreme God of that pantheon. And Asherah his wife is the Supreme Goddess. I have an Asherah Pole for her and everything. I love Adonai very much. He has been kind and loving to him. But so has the Great Mother. May she be blessed always. Oh Supreme Creatrix of the Universe. The Queen of Heaven, who was renamed “the Holy Spirit” in the Bible.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing a part of your book with us. I will have to get myself a copy. I am a huge fan of historical fiction and currently working my way through Kate Mosse’s City of Tears (the sequel to The Burning Chambers).

LikeLike