My introduction to Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898) goes back to my long-standing interest in her son-in-law, L. Frank Baum. I regularly teach Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in my children’s literature courses, and I always point out the book’s feminist qualities. I mention, for example, that Dorothy Gale, the central character in the novel, is one of the first female characters in American literature to go on a bona fide quest. When I first started teaching this book, I wondered what caused Baum, a male writing in the late nineteenth century, to write such a feminist book. One day, while preparing for class, I came across a reference to Gage. This reference stated that Gage was a leading suffragette during the second half of the nineteenth century and that she lived with Baum and his family in Chicago when Baum was launching his career as a children’s author. After reading more about Baum’s life, I realized that Gage played a major role in shaping his nontraditional views on gender roles. However, I was still not sure what role she played in the development of women’s rights.

I had studied the women’s suffrage movement when I took American history courses in college, but Gage was not mentioned in any of these classes. I started doing some research on her, and I was surprised to learn that Gage worked closely with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton during the early days of the women’s suffrage movement. However, her views on the patriarchal underpinnings of Christianity caused her to be viewed as the most radical of the three. As a result, her role in the women’s suffrage movement was downplayed by her contemporaries as well as by those who carried on the movement during the twentieth century.

Gage’s most important book, Woman, Church and State, came out in 1893, but the book was judged to be too radical to be embraced by the leaders of the suffrage movement at the time of its publication, and it has since fallen into obscurity. Having now read this book, I am convinced that Gage’s book did not find a broad audience when it first appeared in part because it was just way ahead of its time. During the late nineteenth century most Americans were simply not ready to consider Gage’s critique of Christianity’s treatment of women. However, Baum not only read the book, but he shared Gage’s determination to question religious dogma and dictates, including religious-based assumptions about the subjugation of women.

Gage first articulated her thoughts on the relationship between Christianity and the status of women during a speech that she delivered at the annual convention of the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1878. In this speech, Gage spoke out against “the wrongs inflicted upon one-half of humanity by the other half in the name of religion.” Over the next fifteen years, she continued to conduct research on the history of this topic, paying particular attention to the status of women in pre-Christian societies. Her research culminated with the publication of Woman, Church and State.

Part historical treatise and part political manifesto, Woman, Church and State traces the impact of religion on the status of women from ancient times to the late nineteenth century. The book begins with a discussion of the “liberty woman enjoyed under the old civilizations” prior to the rise of Christianity. Gage calls this period in human history the “Matriarchate.” She then goes on to argue that with the rise of Christianity women were relegated to an “inferior and secondary position” as compared to men. She calls this period in history the “Patriarchate.” She critiques the theological underpinnings for this change, especially the supposition that a woman was the cause of original sin.

Gage devotes most of her book to examining the ways in which the rise of Christianity affected women in terms of marriage, legal rights, education and work. As she points out in nearly every chapter, throughout the history of Christianity religion was often used to justify the abuse of women on the grounds that women’s subordination to men was divinely ordained. For example, in her chapter titled “Wives,” she writes about the dismissal of court cases in Chicago in which wives were the victims of crime. She goes on to denounce the “tendency of magistrates to ignore crimes perpetuated by men against women” because the magistrates saw such behavior as “being the natural result of the teaching of the church in regard to woman.”

In Gage’s fifth chapter, titled “Witchcraft,” she spells out how organized religion often labeled and persecuted women healers and other independent women as “witches.” When Baum read Woman, Church, and State, he was especially intrigued with the chapter on witchcraft. Baum agreed with Gage’s argument that the women who were accused of being witches were not necessarily evil or wicked, and he eventually went on to include good witches in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Gage concludes her book with a rousing chapter titled “The Church of Today” in which she issues a call to action. She argues that for women to achieve full equality with men, women need to reject the teachings of Christianity regarding gender roles and the status of women. She writes, “In knocking at the door of political rights, woman is severing that last link between church and state; the church must lose that power it has wielded with changing force since the days of Constantine, ever to the injury of freedom and the world” (534). For Gage, this struggle has an internal dimension. As Gage sees it, the struggle for equality is made more difficult when Christian women accept on faith the teachings of the church. Cage does not reject religion outright, but she calls for women to think critically about the gender-biased assumptions behind Christianity. Even in her dedication to the book, Gage implores “all Christian women and men . . . to Think for Themselves” (3).

Gage died a few years before the publication of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, but her questioning spirit and her belief in gender equality lives on in the pages of Baum’s classic. Gage ‘s Woman, Church and State clearly played a role in shaping Baum’s feminist-leaning views on gender roles.

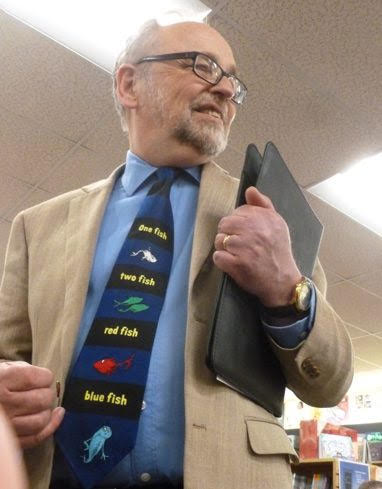

BIO: Mark I. West is a professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he has taught courses on children’s and young adult literature since 1984. He has written or edited over twenty books, the most recent of which is the Broadview Edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which he co-edited with Dina Schiff Massachi. In addition to featuring the work itself, this edition includes an introduction, explanatory notes, chronology, bibliography, and a selection of writings that influenced Baum, including a substantial excerpt on “Witchcraft” from Matilda Joslyn Gage’s Woman, Church and State.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This is so interesting! Thanks for sharing. Now I want to know more about Gage!

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind feedback. Gage is a fascinating feminist who was way ahead of her time. You might want to check out Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Feminist.–Mark West

LikeLike

Wow, I had no idea that Matilda Joslyn Gage was the mother-in-law of Frank Baum and that she had such an impact on his writing, especially “The Wizard of Oz.” How fascinating!

LikeLike