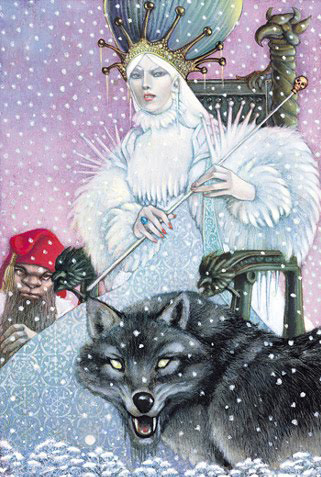

When I first encountered the Narnia novels as a child, the Christian symbolism was lost on me. I grew up in Istanbul, and what captivated me most was the magical world of Narnia, where one of my favorite characters, Aslan, had a Turkish name—a rarity in the British children’s books I read at the time. I also loved the mention of Turkish delight, which I did not consider to be “exotic;” rather, it was an ordinary reference to the rose, lemon, and pistachio flavored confections I often enjoyed at home. However, the character who truly fascinated me was Queen Jadis, also known as the White Witch. Her cold, regal majesty—draped in furs and gliding across a snowy landscape in her sleigh—was enchanting. I preferred witches to princesses and was drawn to stories where characters defied the roles they were expected to play, so it’s no surprise that I found the Witch’s character far more compelling than Lucy’s or Susan’s. I even had a picture of Jadis pinned to my bedroom wall. Yet within myself, I suppressed the Witch’s more admirable qualities—her anger, conviction, and sense of personal power. It took me years to reclaim, heal, and integrate these aspects.

Much has been written about C. S. Lewis’s restrictive and problematic portrayal of female characters. He perpetuates misogyny in Christian thought by depicting women who are idealized, distracted by ‘nylons and lipstick,’ in need of protection, or portrayed as liars—like Lucy, whose discovery of Narnia is initially dismissed as a childish fabrication, even though she is a truth-teller. Traces of paternalism run throughout his works, particularly through his reinforcement of a rigid gender binary. He perpetuates the view that women must suppress their own desires and dreams, in favor of being useful and serving others. Although the Narnia novels may appear to position women like Lucy and Susan as capable and responsible leaders (especially when they are crowned co-rulers of Narnia), this vision of female leadership is complicated by the presence of villainous witches and Queens.

The portrayal of women in fantasy can often be hostile and misogynistic, a challenge that readers of the genre must confront. In many ways, Queen Jadis embodies the archetype of the female sorceress and seductress, symbolizing vanity, power, and everything Lewis deems inappropriate. She is one of the few characters who knows ‘The Deplorable Word,’ a secret curse capable of extinguishing all life. Hauntingly beautiful and imposing, Jadis can ‘see through walls and into the minds of men.’ She brings eternal winter to Narnia, and Lewis’s depiction of the White Witch echoes Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen, who is most visible at the place where snowflakes gather most densely. Described as ‘a great lady, taller than any woman Edmund had ever seen,’ Jadis is draped in white fur and is adorned with a golden crown. As the cruel usurper of Narnia’s throne, she stands in stark contrast to Aslan, representing anti-Christian leadership and temptation. Is it a coincidence that Lewis chose Turkish delight to symbolize temptation and sin? When Edmund eats it, he becomes completely enchanted, willing to betray his family in his desperate craving for more.

It’s intriguing to consider Jadis as one of the few adult female characters in Narnia. In patriarchal societies, powerful women are often cast as evil, especially those who defy gender norms. These women are frequently marginalized, cast out, discredited, or punished. Filmer argues that Jadis represents ‘a clear instance of devilry being identified as female,’ and serves as an example of the ‘Great Goddess’ figure from which many sinister female literary characters are drawn. Brennet cites Miller, who aligns “the White Witch [with] the frosty tradition of the Snow Queen, [and] the Lady of the Green Kirtle, or the Green Witch, in the merrier spirit of Celtic sorceresses. These two… want power. Vain, silly women may be annoying distractions for men who have better things to do; the witches are seducers.” Jadis’s backstory is further revealed in The Magician’s Nephew. Born into the royal family of Charn, she is part-Jinn and part-Giant. Her alignment with Eve is suggested when she eats an apple from the Tree of Youth. In my own culture, Jinn were well known to me; my grandfather had many stories of the Jinn who would come out after dark and lurk at the roadside.

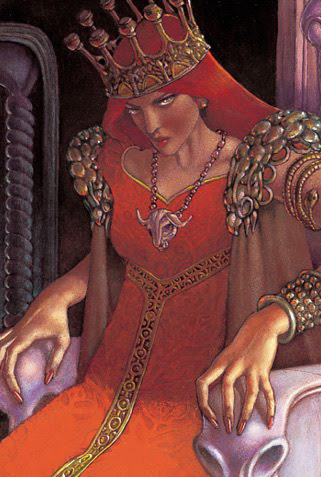

In The Silver Chair, the main antagonist is the Lady of the Green Kirtle, also known as the Queen of Underland and Queen of the Deep Realm. She attempts to hypnotize Eustace, Jill, and Puddleglum into believing that Narnia and the Earth do not exist; when that fails, she transforms into a serpent. While her backstory is more ambiguous than the White Witch’s, both Jadis and the Green Lady are classified as witches, and some readers even speculate that they may be the same person. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Edmund is initially captivated by Jadis’s beauty, but it’s her display of power that truly draws him in: ‘It was a beautiful face in other respects, but proud and cold and stern.’ Similarly, in The Magician’s Nephew, Digory reacts to Jadis with admiration, saying: ‘She’s wonderfully brave. And strong. She’s what I call a Queen!'”

There is much debate surrounding the depictions of Narnia’s witches and Queens, what their power represents, and whether they offer pathways for true empowerment. Although I find Narnia’s witches fascinating, it seems to me that Narnia’s visions for Queendom replicate familiar scripts that are sceptical of non-male authority and power, and subscribe to strict gender binaries, scripts in which female characters may aspire to bravery, demonstrate courage, and even become rulers—as seen through the pathways of Susan and Lucy, who are crowned “Queen Lucy the Valiant, and “Queen Susan the Gentle”—however, their successes as Queens and their spiritual attainment seems contingent on their likeability, and the requirement that they must also be “good.”

I have collected many editions of the Narnia novels over the years, and Narnia was a place I spent many years trying to find. I continue to reread these books as an adult and see them with new eyes. I think back to the ways in which my own childhood was mediated by British books, the English language, Christian messaging, and the ways in which aspects of my Turkish culture were aligned with the White Witch and with Aslan—two figures who offer contradictory visions for leadership. As I grew into adulthood, I have embraced my bilingualism and my multiple frames of reference as a reader, although I still catch myself reaching for the back of wardrobes, hoping to catch a hint of pine in the air, carried on a sudden gust of winter wind.

References:

Brenett, Niki. (2014). “In Defence of Women: Exposing the Sexist Portrayals of Women in Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia.” https://scholar.umw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=student_research

Filmer, Kath. (1993). The Fiction of C. S. Lewis. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Lewis, C.S. (1950). The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Lewis, C.S. (1953). The Silver Chair.

Lewis, C.S. (1955). The Magician’s Nephew.

Artwork of Leo and Diane Dillon: https://leo-and-diane-dillon.blogspot.com/2010/05/chronicles-of-narnia_26.html

Bio: Elanur Williams writes from New York City, where she lives with her husband and daughter. She holds a B.A. in English and Creative Writing, an M.Phil. in Children’s Literature, and M.S.Ed. in Literacy Studies. A teacher by profession, she has taught in elementary school and adult education settings, specializing in reading and writing instruction.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

we are all products of western conditioning – fairy – type stories can provide an archetypal root for behavior – fascinating really.

LikeLike

Hi Sara,

Thank you for your comment! Absolutely—there’s something deeply compelling about the way stories can shape who we are, and the potential they have to guide our choices, behaviors, and dreams.

Best wishes,

Elanur

LikeLike

This is an excellent piece!

LikeLike

i love what you note about having a broader frame of reference to enter into “story” given your immersion in more than one culture. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Esther,

Thank you for your reply, and I appreciate your engagement with the piece! Am grateful for your kind words and encouragement.

All the best,

Elanur

LikeLiked by 1 person