Moderator’s Note: This piece is in co-operation with The Nasty Women Writers Project, a site dedicated to highlighting and amplifying the voices and visions of powerful women. The site was founded by sisters Theresa and Maria Dintino. To quote Theresa, “by doing this work we are expanding our own writer’s web for nourishment and support.” This was originally posted on their site on November 30, 2021. You can see more of their posts here.

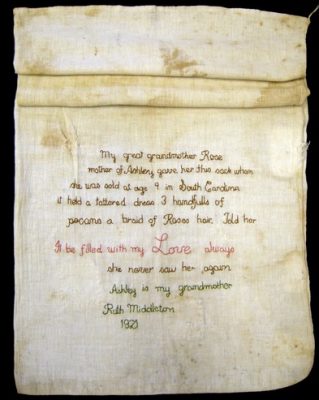

First she was told about a grain sack dating from around 1851 that had these words embroidered on it:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my LOVE always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

Taken in by its story and the sack itself, which apparently elicits raw, sudden and spontaneous tears in those exposed to it, Tiya Miles was compelled to write a book about it and the women’s stories that briefly appear on it: All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake.

In so doing, she uncovers and recovers the herstory of enslaved mothers and daughters, the long trajectory of a strong Black culture in the US, the emergence and story of Charleston, South Carolina as a hub of the worst kinds of crimes against humanity, the location and ecosystems of pecan trees and the importance of their nutrient rich seeds in the survival, folk history, and eventually, food culture of Black Americans, and much more.

I love the approach Miles takes: researching each line and filling in the multitude of blanks between the lines. Through her research, so full of heart as well as sharp intellect, she is able to locate the women who were Rose, Ashley and Ruth. She is able to piece together their heartbreaking stories, while also reconstructing the untold story of Black women. In Rose’s ability to find a way, any way she could, to care for, prepare and support her daughter Ashley under such heinous conditions and circumstances, Miles blows the cover off the myth that the enslaved were not active in their own narratives. Somehow Rose found a way and it was mindful, intentional and clear. How many more invisible acts of this kind were there that we have never and will never hear about. The erasing of the stories of women who were unfree adds to the massive effort at dehumanization they were up against. We must take Miles’ lead to regain, reclaim and tell their stories to give them back in part what was taken from them and do whatever small part we can toward restoration and remuneration. Telling their stories and offering respect can be part of those efforts.

“Rose’s packing highlights an essential element of enslaved women’s experience. Black women were creators, constantly making the slate of things necessary to sustain the life of the family. . . These made things included clothing, brooms, quilts, meals, medicines, and an array of mementos, like buttons and beads, that might one day be pressed into the palm of a parting loved one’s hand. Black women fashioned and gathered these things into emotional nets that affirmed their love for self and others, channeling visions of perseverance through the work of their thoughts and hands, often at their own risk”(103).

In this book, Miles tells the intimate and untold story of women who were unfree, women who were legally enslaved in the United States of America. The only records that are mostly available about them are their names recorded in ledgers on the dates they were bought or sold. Sometimes people find letters, if they are lucky. By finding their names recorded on the sack and matching them to names on ledgers with dates and locations, Miles is able to piece together the realities of the lives of Rose, Ashley and Ruth. She accomplishes this by researching the history of the time and location. By researching the choices Rose made about what she put into the sack, researching the story of women’s relationship to cloth in general, to clothing, to sewing, to grain sacks, to fabric, she adds more. By finding other Black women at the time who did manage to speak or write their stories, she is able to further cull the story and fill in the details. Miles’ process in writing this book creates a strong model for how to write about what has been erased, excluded and removed from history in general.

Read Nasty Women Writers’ post: Tiya Miles and Saidiya Hartman: Critical Fabulation – Claiming the Narrative and Overriding the Supremacist Archive

Ashley’s sack was discovered by a white woman “in a bin of old fabrics at an outdoor flea market near Nashville Tennessee”(31) in the early 2000s. It is now housed in a case at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC, on loan from the Middleton Place Foundation in Charleston, SC.

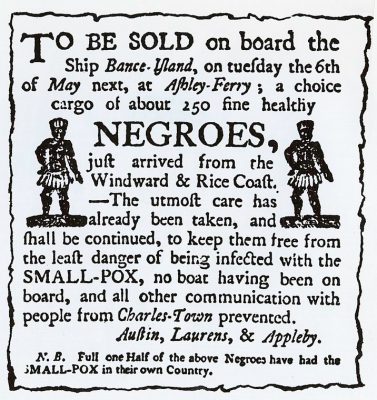

Miles informs us that the history of South Carolina has its roots in the British landowners and the slave economy from England through Barbados,“the largest, most comprehensive, most lucrative slave society all the English colonies”(43). Apparently this economy along with its worldview and citizens migrated to Charleston, where Ruth ended up and Ashley was born.

“There is a prologue to Ruth’s family story that traces back to colonial South Carolina, the darling of coastal planters, and its bustling, bedazzling seaport city: Charleston. Restarting our story then and there grounds the unfolding drama of the sack and its carriers in the historical evolution of Lowcountry slave society.

If the old cotton sack is synecdoche for American slavery, Charleston represents the same for eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century South during the long reign of rice and the bright rise of cotton, staple crops dependent on rich, abundant land, and cheap, plentiful labor. Over a few short decades, people rendered as things by law became fundamental to the establishment of this colony and metropolis”(42).

Miles explores and relays facts and anecdotes about the Charleston of that time so we can get a real feel for the place, customs, beliefs and treatment of the unfree Blacks there. It is in the context of this Charleston that the first two lines of the sack unfold, where the daughter is ripped from the mother—an event that without Ruth’s documentation on the sack, we would never know anything about. And yet it happened all the time. A completely normalized event for the enslavers and white people of the time, but one that was never normalized for those to whom it was happening. The tearing apart of families and other relationships was one of the worst crimes of the enslavement of Black Americans.

“How did we end up here, with the memory of a tattered dress and yet another Black mother’s daughter on an auction block? How did South Carolina become a place where the sale of a colored child was not only possible but probable? The answer lies in the willingness of an entire society to bend its shape around a set of power relations that structured human exploitation along racial lines for financial gain. While vending Black people to underwrite material pleasures, South Carolina sold its soul”(165).

Part 2, tomorrow

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fascinating and powerful! Thank you, Theresa, for posting this important piece. Look forward to Part 2.

LikeLike

wonderful/powerful – when I read the words “The answer lies in the willingness of an entire society to bend its shape around a set of power relations that structured human exploitation along racial lines for financial gain.” I find I could easily apply them to our current situation – yes?

LikeLike

The grain sack carries the physical, emotional and spiritual weight of history. A beloved aunt once gave me a braid of the red hair of her youth, which I still carefully keep. The sack has layers and layers of meaning. And the word “Love” is the largest of all. This is a precious treasure.

LikeLike