The parshah I will discuss this month is Pinchas, Numbers 25:10-30:1. It was last read in synagogues on the 19th of July 2025. It covers dealings of a zealous deity, declarations of war, descriptions of animal sacrifices and grain offerings, a census for inheritance and possibly also conscription, and the case of five daughters who seek their inheritance. As I have done a number of times, I will focus on the women in the parshah using the methodology I have laid out in numerous commentaries (but do not always follow).

However, before we get into the heart of the matter, I also want to mention that Pinchas also marks the last parshah on my pursuit to comment at least once on each Torah parshah. Of course, there is so much more that I could say about the Torah and each and every one of its parshiyot (Note 1); from a feminist and ecofeminist perspective, I have just scratched the surface. Yet, I am also happy to have accomplished this milestone. Now, back to the parshah.

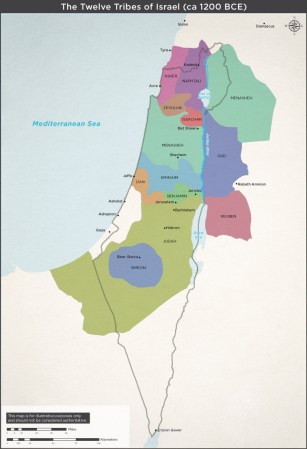

There are numerous mentions of women in Pinchas. Kozbi is the victim of a murder (25:14-15). Serach is Asher’s daughter (26:46). Yocheved is counted as one who entered Egypt (26:59), and she is named as the mother of Moses, Aaron, and Miriam (26:59). Machlah, No’ah, Choglah, Milkah, and Tirtzah are the five daughters of Tzelofchad, who seek their rightful inheritance (27:1). Finally, daughters are granted certain inheritance rights (27:8-9) thanks to the challenge brought to the community by Machlah, No’ah, Choglah, Milkah, and Tirtzah.

Of all of the 54 parshiyot, this might be the parshah with the most named women–nine in all. On top of this, a number of the women are quite prominent in the tradition. We have here Yocheved, the mother of Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, who is mentioned in the census taking among a huge host of only men’s names. Rashi reasons that she is include in order to account for internal consistency within the Torah of the 70 persons who entered Egypt (26:59 and Rashi’s commentary to the verse), yet could there be another reason? She is, after all, the mother of the most important people – Miriam, Aaron, and Moses – who lead the Israelites out of Egypt and throughout their wanderings in the desert. Miriam is the sister of Moses and a priestess/prophetess in her own right. Her considerable significance to the Israelites I have discussed here. From these two examples, I would also conclude, although we cannot say for certain, that Serach (26:46) must have also been a very important woman to the community, although why seems to have been lost to the sands of time. Rashi’s explanation that she is named because she was alive at the time is nonsensical as then the census should be full of women and it isn’t. Kozbi, the victim of a murder and a foreign princess, must have also played an important role or been an important person to the community. Her murder is recalled as is her name, even though it is sadly used to justify the Israelites call to arms against her people, the Midianites.

I want to end this exploration of the women of Pinchas with Machlah, No’ah, Choglah, Milkah, and Tirtzah, the five daughters almost left without an inheritance. Rashi’s commentary on this situation is plain sexist (27:4, 7). He says that these five women would have never approached the community for their inheritance even if there was a male within their family who was too young to inherit. Thus, they would have followed the patrilineal inheritance and thus patriarchal rule of the Torah. This is rather assumptive of their intentions and what he considers to be their righteousness within the community. Then, in 27:7, he denigrates men by conflating the lack of an heir to a situation of divine wrath. In other words, any man who fails to produce, or is not actively working towards producing a male heir earns divine anger. Clearly, the world of men and its reproduction is the only world that matters for Rashi here.

Obviously, I disagree with Rashi’s sentiments. It is equally if not more plausible that Machlah, No’ah, Choglah, Milkah, and Tirtzah approached the community and demanded an inheritance when they saw land was being distributed and they were being left out, because they thought they deserved it as people, as Israelites, and as members of the community. They could have approached the community leaders as an act of justice while the land was being distributed, specifically because they wanted to speak up for all of the women who were in a similar situation to them. Most likely, they were not the only group of women who may have been left out of land inheritance at the time, and their “boldness” may have also benefited those whose status in the land was marginalized, like strangers, orphans, and widows. Now, these are actions of righteousness! (Righteousness does not come from blind adherence to patriarchy as Rashi contends.)

It is also possible that these women may have been very well known within the community, and the community wanted to provide for them and their descendants even though they didn’t fit the criteria. However, their story and was then told in such a way so that they, as women, would fit into the world of men in which the Torah was composed and compiled. Nevertheless, these women did change his-story and they are credited even in the Torah with all Israelite daughters having inheritance rights (27:8-9). At the same time, we will never know exactly who these women or any of the named women in Pinchas were. Thus, we have to invent them (as I have mentioned in Naso) and give them stories previous men denied them.

The women of Pinchas, then, remind us that the work of feminism is not over. In fact, that work may take several more lifetimes, but the work will be done. May we live up to the legacy of the women whose names were remembered even when their lives and contributions were not. May we write them new stories one day soon.

NOTE 1:

Over the past 7 years or so, I have throughout this exploration of the Torah consistently used the word parshot as the plural form of the term parshah, the Hebrew term of a portion of Torah. However, parshot is technically incorrect, although it is often used in some Ashkenazi communities, and I used it for years without even thinking that it might be incorrect, and then when I realized I had been writing it wrong all of these years, I hesitated to change my vocabulary so as not to confuse people. I suppose there is no better time to admit to this mistake than for the last parshah. On a related side note, even parshah is sometimes written parasha or parsha. Hebrew in transliteration and/or according to tradition or heritage can be a funnily inconsistent language. For more on the plural of parshah and the word parshah in general, see here: https://tanach.org/breishit/brintro/brintro1.htm (although I think this may only add to the funny confusion that is Hebrew terminology.)

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Kol Hakavod, congratulations on covering all the parshot (I am never sure about the plural myself). What a refreshing perspective it has been. Perhaps you could compile them all into a book!

LikeLike