This autumn I am once again in southern Morocco, bringing friends and students to experience traditional Berber women’s dance and culture.

The Berbers or Imazighen* are the indigenous people of North Africa, who have lived for at least 12,000 years in the Maghreb region (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Mauritania, and Western Sahara). Within this vast area, different Berber tribes follow various forms of social organisation, yet remain linked by language, culture, and a shared sense of identity.

Among the Berbers,

The ‘religion’ of women is expressed in the cult of the family, in religious practices performed close to their environment and in the management of clairvoyance and healing within the domain of the traditionally sacred… [The] domain of the sacred is found in the family community as it extends to the village, according to social relations determined by a spirit of collective responsibility. This is found between the living but also with the Ancestors. – Makilam

Even though the Souss Valley and Anti-Atlas mountains of Morocco where we are travelling is far from the Kabylia region of northern Algeria Makilam describes, her comments also apply here.

Berber spirituality combines elements of pre-Islamic and pre-patriarchal ritual and belief with the Sufi mysticism which has permeated Morocco for 700 years. The women’s practices ‘in the domain of the sacred’ which Makilam mentions, which unite people, environment, and ancestors through ‘a spirit of collective responsibility’, can be experienced in southern Morocco in many ways. Central among these is the veneration of Sufi saints – holy women or men – whose tombs or marabouts are places of gathering, pilgrimage, and prayer.

Marabout of Sidi Mullah Abdel at Tioute oasis, with threshing circle in the foreground. Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco. (Photo: Laura Shannon 2018)

As Makilam explains, ‘Islam was only able to enter Kabylia by integrating with the cult of the Ancestors.’ Through the custom of honouring marabouts, the cult of the Ancestors became assimilated into the cult of the Saints.

The word marabout (from murābiṭ, a Maghreb Arabic word for Sufi teacher) applies to both the saints and the shrines. Marabouts are tiny domed structures where people gather for healing, blessing, and community, often once a year on the anniversary of the death of the saint. Marabouts are seen as sources of baraka – divine grace and blessing – emanating from both the place and the person buried there. The ancestral influence of the wise woman or man gives grace and guidance which continue in the world of the living long after the saint has left the earthly realm.

These shrines are plentiful. In the words of Moroccan Berber author Tahar Ben Jelloun, ‘This natural appearance of the Marabout in the smallest village or douar is a sign of a deep spirituality, beyond dogma. They are neutral spaces where silence helps to heal the internal wounds of visitors. We pass through Morocco and they are seen everywhere, sometimes even along roadsides.’

While the saints may be either male or female, female marabouts (known as tigrramin) are especially important for Berber women. Aziza Ouguir points out, oral narratives celebrate ways that ‘women saints transgressed the social limits that were imposed on them, and refused the conventional patterns that they were supposed to embody’ – so stories of the lives of the tigrramin offer important examples of alternatives to the strict obedience requested by traditionally patriarchal Islam.

Ritual practices in connection with these ancestors remain largely in women’s hands. Fatima Sadiki explains that Berber women ‘visit saints for a variety of reasons: search for solace, expressing faith, socializing with other women, talking about deeper concerns, or simply enjoying a moment away from a harsh reality.’

As Makilam clarifies, ‘Islam, based on the sacred texts of the Koran, is a man’s religion. It has not affected the Kabyle women of traditional society, who have been kept away from Arabic and French writings, which they are unable to read.’ This is true of the Berber women of southern Morocco also, where (as in Kabylia) women’s ritual and spirituality are transmitted through orature, often through music, song and dance.

Usually, when I bring my groups to the Tafroute region of the Anti-Atlas mountains, we invite one of the well-known women’s groups, the Bnat Louz, to share their ritual communal dance called Ahouache. They were unable to meet with us this time because our visit coincided with the annual festival (moussem) of the beloved local marabout of Sidi Abdel Jabar, and their presence was required there.

I was sorry to miss dancing with the Bnat Louz, whom I adore, but feel grateful that our group got to visit the moussem instead – not the ceremonies inside the mosque, which are not open to outsiders, but the associated market (souk) as well as the men’s Ahouache dance, which took place late in the evening.

Zaouïa Sidi Abdel Jabar, with the start of the moussem souk just visible in the far background. Tafraoute, Anti-Atlas Mountains. Photo: Laura Shannon 2025.

This souk was unlike any other North African market I have seen. Stretching for a couple of kilometers from the mosque of Sidi Abdel Jabar along the single road through the Amelne valley, a long line of stalls offered fruit, clothing, jewelry, antiquities, herbs, cosmetics, and foodstuffs including dates, nuts, sweets, and snacks. Tasty flatbread came fragrant and steaming from rounded clay ovens which were built on site just for the festival and broken down again afterwards. Everything one buys at a moussem is believed to be imbued with the baraka or blessing of the saint, and people traditionally buy small gifts for loved ones who can not be present. Perhaps this accounted for the extraordinary atmosphere of calm and peace which reigned, even amongst the throngs of visitors.

After a pleasant morning spent purchasing rosewater, argan oil, dates and other delicacies as well as several items of antique jewellery, we rested to gather our strength for the nighttime performance of Ahouache dancing. This was to be my first visit to a moussem and my first experience of the men’s Ahouache.

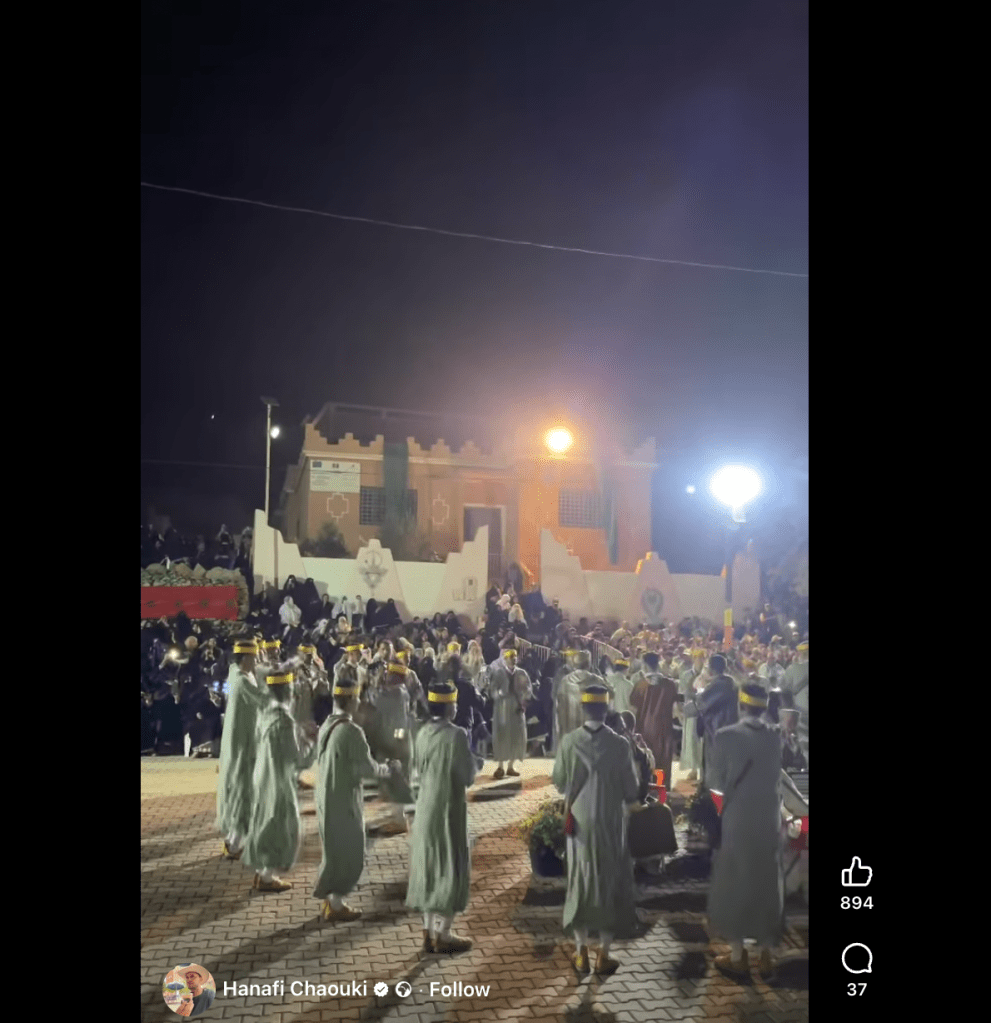

Men’s Ahouache dancers, Moussem of Sidi Abdel Jabar, Tafraoute. Photo: Hanafy Chaouki, 2025.

In many ways the men’s Ahouache resembles the women’s, which I have seen many times: a group of drummers provide fantastic polyrhythms, while the dancers sing poignant call and response melodies in unison in the archaic pentatonic mode. Steps, movements, and formations were all similar, performed with a blend of relaxation and vitality, and characterised by complex shoulder movements, shaking up and down with extraordinary flexibility and synchronisation.

There is one major difference: male Ahouache dancers reveal their faces, whereas women cover their heads completely with a single communal veil, as seen in this photo taken from one of the Bnat Louz Youtube videos.

Ahouache Bnat Louz, Tafraoute, Morocco, 2014. Photo courtesy Bnat Louz.

This long, wide communal veil serves the cultural custom of protecting women’s faces from the ritually harmful gaze of strangers, but also emphasises the transpersonal nature of their collective dance:

The ritual dance circle where all women are dressed alike subsumes individual characteristics… to help women overcome the limitations of personality and to serve on ritual occasions as archetypal representatives of the feminine…. [T]he dancers become aware of the divine feminine embodied within them, as a force vastly larger than themselves but of which they are inextricably a part.

– Laura Shannon (2011)

The dancers transmit this awareness to the onlookers as well, as they dance in honour of their local saint and spread the baraka of this spiritual ancestor to everyone present. In this ritual act, the veiled women use the medium of textile to transcend individual identity so they can bestow blessings from a transpersonal level. In this way, I suggest they temporarily take on the role of the ancestors they themselves will one day become.

As always, the dancers prayed for rain; a few drops fell, but not enough. It is bitter to think that the Berber people – after thousands of years resisting invasion by Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, French, Spanish, and rival tribes – might finally and permanently lose their land-based livelihoods to the deadly threat of long-term drought.

In any case, the prayers and the dances will continue here and in many other places. Please, today, on this day of the ancestors, in honour of Mother Africa where all of humanity has ancient roots, spare a moment to pray for rain.

* ‘Berber’ is how my Moroccan friends refer to themselves and each other, but it should be noted that many reject this term because of its origin (in the Greek várvaros, ‘barbarian’, lit. ‘people who do not speak Greek’) and its frequently derogatory connotations. Instead, many people nowadays prefer the ethnonyms Amazigh (singular) and Imazighen (plural), meaning ‘the free people’, and Tamazight for the Berber languages of Morocco and Algeria.

References

Becker, Cynthia (2006). Amazigh Arts in Morocco: Women Shaping Berber Identity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Lièvre, Viviane (2008). Die Tänze des Maghreb. Frankfurt: Otto Lembeck Verlag.

Makilam (2007). Symbols and Magic in the Arts of Kabyle Women. New York: Peter Lang.

Ouguir, Aziza (2020). Moroccan Female Religious Agents. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

Sadiki, Fatima (ND). Oral Knowledge in Berber Women’s Expressions of the Sacred. New York: Cornell.

Shannon, Laura (2025). ‘Asherah and Taghonja’ in Asherah: Roots of the Mother Tree. Eds. Dorey, Rudolph, Daly, and Hendren, with a preface by Miriam Robbins Dexter. Girl God Books, 2025.

Shannon, Laura (2025). ‘Asherah and Taghonja: A rain ritual with ancient roots.’

Shannon, Laura (2024). ‘Thirst for Knowledge, Thirst for Rain: Women’s Seeds and Symbols in Southern Morocco‘.

Shannon, Laura (2023). ‘Dancing for Rain: Life-Giving Gift from Heaven to Earth.’

Shannon, Laura (2019). ‘What I Learn from Women in Southern Morocco‘.

Shannon, Laura (2011). ‘Women’s Ritual Dances: An Ancient Source of Healing in our Time’, in Dancing on the Earth: Women’s Stories of Healing Through Dance. Eds. Leseho and McMaster. Findhorn Press.

Resources:

Men’s Ahouache dancing at the Moussem of Sidi Abdel Jabar in Tafraoute, on Hanafy Chaouki’s Facebook page.

The souk at the moussem of Sidi Abdel Jabar in Tafraoute, on Hanafy Chaouki’s Facebook page.

The women’s Bnat Louz Ahouache group from Tafraoute.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I am struck by these words ” the veiled women use the medium of textile to transcend individual identity so they can bestow blessings from a transpersonal level” I think this veiling can be seen as positive as you explain in this essay – veiling has advantages allowing the transpersonal to merge – fitting for this First Day of the Dead..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, exactly, Sara! I do see a connection with the masks of Halloween which allow children to ‘veil’ their everyday identities and to take on characteristics of otherworldly beings, often those with nonhuman / superhuman powers.

LikeLike

I think the masks belong to winter solstice fire when they are donned to personify trickster qualities by ADULTS – the masks of halloween aren’t children’s playthings – the old festivals understood this

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing Amazigh culture but I’d like to educate ppl we don’t like the term Berber 🥰 we are Amazigh people! We wish people to call us our true name ! 🫶🏽 Berber is a derogatory term given by colonizers that means barbarians which we are far from! We are a very advance people in culture & language 🙏

LikeLike

I actually talked about Berber religion briefly in my article about the Black Goddesses of Candlemas

LikeLike

Dear Laura, many thanks for your researches and detailed information about the Ahouache Dance. As part of your last group I have had the privilege to visit the Moussem of Sidi Abdel Jabar Festival with you. The night festival with the mens Ahouache dance was impressive and very powerful. And sitting among all this Amazigh woman wearing the traditionelle clothes of their region was so special. Of course we exchanged curious looks each other and also some words in a friendly atmosphere We where lucky getting the permittion to come and see thanks to Lauras good contacts.

Thank you Laura for this insight in one little part of the Berber culture. I will remember this experience and of course all experiences of the whole morocco group tour with you for a long time.

Thesi Jamnansribejra, Hamburg Germany

LikeLike

Dear Laura, many thanks for your researches and detailed information about the Ahouache Dance. As part of your last group I have had the privilege to visit the Moussem of Sidi Abdel Jabar Festival with you. The night festival with the mens Ahouache dance was impressive and very powerful. And sitting among all this Amazigh woman wearing the traditionelle clothes of their region was so special. Of course we exchanged curious looks each other and also some words in a friendly atmosphere We where lucky getting the permittion to come and see thanks to Lauras good contacts.

Thank you Laura for this insight in one little part of the Berber culture. I will remember this experience and of course all experiences of the whole morocco group tour with you for a long time.

Thesi Jamnansribejra, Hamburg Gernany

LikeLike

The photo of the Women with the communal veil appears golden to me. With their yellow arms the individual and whole appear as the sun. Gorgeous!

thanks again for sharing your experience and knowledge with us!

lots of love. nada

LikeLike

The communal veil in the women’s photo appears golden to me. With their yellow arms I see the sun individually and collectively. The radiance of the divine feminine brilliant and bright.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful experience and your wisdom and knowledge.

lots of love. Nada

LikeLike

I had trouble posting so now it’s amplified! :)

LikeLike

Amazing and heart-rendering touching. Thank you for this sharing. Arose in me: Guided by one veil, one power, one womb, one Heaven, one Earth, one mother golden ancestor….

LikeLike

The collective veil is relatively new. Pictures from the mid-20th century show no trace of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person