I never imagined I’d paint her. Though I was not raised in church, I have vivid memories of worshiping in Southern Baptist Churches, churches where women’s voices were not permitted behind the pulpit, churches where women could never dream of ordination, churches that damned LGBTQ folks to hell with a pound of a fiery fist on a well-worn bible perched atop an angry pulpit. Canonize a Southern Baptist woman into the sainthood of Holy Women Icons? No, thank you.

I never imagined I’d paint her. Though I was not raised in church, I have vivid memories of worshiping in Southern Baptist Churches, churches where women’s voices were not permitted behind the pulpit, churches where women could never dream of ordination, churches that damned LGBTQ folks to hell with a pound of a fiery fist on a well-worn bible perched atop an angry pulpit. Canonize a Southern Baptist woman into the sainthood of Holy Women Icons? No, thank you.

Though I am an ordained Baptist minister myself, it’s important to remember that there is a vast spectrum of belief and practice when it comes to the Baptist church. Because our polity is non-hierarchical and we are anti-creedal, one cannot easily say, “All Baptists believe ______ or all Baptists practice _______.” Whether you are as conservative as the Southern Baptist Convention or as liberal as the Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists, we all share some core Baptist distinctives: the separation of church and state, believer’s baptism, the autonomy of the local church, freedom of conscious, and the priesthood of all believers. Learning of these distinctives as a young feminist searching for a faith to call my own, I was immediately drawn to the core Baptist tradition. They reject hierarchy. All are supposed to be equal. It is up to the individual conscious to determine what one believes. And it is up to the individual church to determine how that particular community of faith will practice those beliefs. It is feminist to its core. Southern Baptists feel otherwise, which is why they refrain for ordaining women and claim that they should be submissive to their husbands.

So, when a friend and colleague who attended seminary with me wanted to commission an icon to inspire her daughter, Lottie Moon’s namesake, I was skeptical to say the least. I was concerned that canonizing this seemingly holy woman would elevate attributes that have been used to oppress and marginalize women for centuries. Because I trust this friend and colleague, I decided to set my preconceived notions aside and listen. I listened to why this feminist mother thoughtfully and intentionally chose to name her first child, her beloved daughter, after Lottie Moon.

Like me, this new mother has a love/hate relationship with the Southern Baptist Church. She loves elements of her childhood and family that were nurtured there, but she rages against the way the SBC treats women today. But she’s always loved Lottie Moon’s story. Born in December of 1840, Charlotte Digges Moon, “Lottie,” said and did things unheard of for women of her era. At a meager four feet and three inches tall, she followed a call from God to go to China as a missionary, an occupation rarely afforded women in the Baptist faith—or any faith—during this time. She began her mission in China with appalling views of the Chinese people, but over time she allowed herself to be transformed by her neighbors, eventually embodying Chinese culture and identifying herself with her neighbors. She came to believe this so fully that she shared her salary, her food, her whole self with her Chinese neighbors until there was nearly nothing left of her. She died weighing only fifty pounds after giving away all her food to those who were hungry.

This feminist mother is typically quite leery of advocating total self-emptying, but she stated that “Lottie did not seem to do it out of some perverse understanding of holiness. She did it out of intense compassion for her new brothers and sisters. She had become one with them. Their plight was hers. Her resources were theirs.” She was a bold and opinionated woman who changed the face of missions and the way women were treated in ministry. Lottie’s namesake’s mother claims, “I think of her as having the intensity of fire all the way to her bones.”

As I listened to my friend, this new mother who named her daughter “Lottie,” I thought of a woman who has been misunderstood. Only instead of society and the church being the ones who misunderstood her, lumping her life and story into the category of “other,” it was I who had misunderstood. I lumped this brave woman—this bold spitfire who sailed into the unknown to teach and feed and empower other women—into the category of “Southern Baptist” and relegated her to a person unworthy of feminist exploration.

So, this month I welcome Lottie Moon into the vast witness of Holy Women Icon with a folk feminist twist that I feature each month: Virginia Woolf , the Shulamite, Mary Daly, Baby Suggs, Pachamama and Gaia, Frida Kahlo, Salome, Guadalupe and Mary, Fatima, Sojourner Truth, Saraswati, Jarena Lee, Isadora Duncan, Miriam, Lilith, Georgia O’Keeffe, Guanyin, Dorothy Day, Sappho, Jephthah’s daughter, Anna Julia Cooper, the Holy Woman Icon archetype, Maya Angelou, Martha Graham, Pauli Murray, La Negrita, Tiamat/tehom, Mother Teresa, Aurora, and many others.

I may not agree with everything about Lottie Moon, I may balk at the notion of trying to “Christianize” a “heathen” people, and I do reject the way Southern Baptists treat women, but there are elements of this tiny woman’s life worthy of canonization. Like Mother Teresa, her actions stemmed from a deep sense of compassion for the least among us. She was bold, courageous, fiery, and did more in the world than anyone would have dreamed given her gender, her faith tradition, and her small stature.

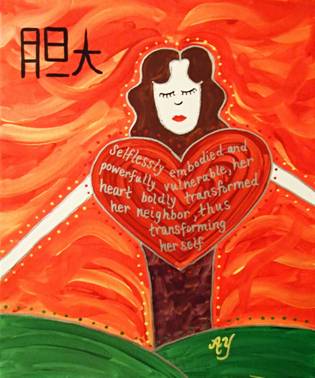

As I painted her into sainthood, I knew that I wanted to pay homage to her much loved and respected China. In the upper left corner I painted the character “Dan Da,” which is Mandarin for “bold.” For years, Lottie Moon studied to learn Mandarin, and this character also has the implications of being a hero or leader that shifts the status quo. Emblazoning the sky around her tiny body are shades of fire—reds, oranges, yellow, and pink—to capture the idea of Lottie being a spitfire. Though I continue to struggle with a self-effacement so deep that one denies one’s self even the basic nourishment of food, I made her very thin based on the sacrificial way she gave away her own food to the hungry. Yet, I wanted this little daughter to grow up knowing she could be strong, so Lottie’s tiny arms are spread big and wide, as her massive heart cries out to us:

As I painted her into sainthood, I knew that I wanted to pay homage to her much loved and respected China. In the upper left corner I painted the character “Dan Da,” which is Mandarin for “bold.” For years, Lottie Moon studied to learn Mandarin, and this character also has the implications of being a hero or leader that shifts the status quo. Emblazoning the sky around her tiny body are shades of fire—reds, oranges, yellow, and pink—to capture the idea of Lottie being a spitfire. Though I continue to struggle with a self-effacement so deep that one denies one’s self even the basic nourishment of food, I made her very thin based on the sacrificial way she gave away her own food to the hungry. Yet, I wanted this little daughter to grow up knowing she could be strong, so Lottie’s tiny arms are spread big and wide, as her massive heart cries out to us:

Selflessly embodied

And powerfully vulnerable,

Her heart boldly transformed her neighbor,

Thus transforming herself.

I am still surprised to find Lottie Moon amidst this great cloud of holy women witnesses that surround me. But I am grateful that there is a little girl growing up gazing at Lottie’s big, bold heart, knowing that she has the capacity to do big, bold things that can change the world. And I am grateful that her mother taught me to give this misunderstood woman a second chance. May we all be so bold.

Rev. Dr. Angela Yarber has a PhD in Art and Religion from the Graduate Theological Union at UC Berkeley and is author of Embodying the Feminine in the Dances of the World’s Religions, The Gendered Pulpit: Sex, Body, and Desire in Preaching and Worship, Dance in Scripture: How Biblical Dancers can Revolutionize Worship Today, Holy Women Icons, and Tearing Open the Heavens: Selected Sermons from Year B. She has been a clergywoman and professional dancer and artist since 1999. For more on her research, ministry, dance, or to purchase one of her icons, visit: www.angelayarber.com

I took some time this morning to read about Lottie Moon at Wikipedia. I can fully understand the challenge you recount in creating this icon and it is kind of you to share that struggle here, thanks, Angela, and helpful in many ways, really, because it speaks to lots of decisions we are all required to make in our work and in our lives where there needs to be a wide-openness to working it through in our understanding.

One thing, though, is that our acceptance today of various spiritual and religious paths is far more inclusive than the era in which Lottie Moon lived, and thus without need to convert people necessarily to “save them.” Learning and gaining inspiration from the many wonderfully different ways of celebrating the spiritual nature of existence, as we do at FAR, is the most important thing to encourage, in my view, if we are truly hoping for a more loving, more integrated world community.

LikeLike

For whatever it’s worth, Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror, is also said to have been just over four feet tall. She’s also said to have been ferocious, a good mother (as things went almost a thousand years ago), and a good ruler while William was out conquering.

Some years ago, I edited a book for a woman in Georgia who later turned herself into a self-publisher who helped other people publish their books. She sent me clients, including an old Southern Baptist preacher. I edited his book, which was one of those fiery sermons,and sent it back to him. Then he went to my website. Found out who I am and what I believe. He removed every single correction and change I’d made in his manuscript. He said I’d put the devil in his book! My friend apologized, but she couldn’t do anything with the old man.

I’ve known a few other Southern (and other) Baptists. Even though they’ve kept trying to bring me to Jesus, they’re kind, sincere people. All’s well when we talk about other things.

LikeLike

I like how you painted her arms going off the page so we can’t see her hands. It’s like she is trying to give the viewer a hug.

LikeLike

“She began her mission in China with appalling views of the Chinese people, but over time she allowed herself to be transformed by her neighbors, eventually embodying Chinese culture and identifying herself with her neighbors.” This was similarly true of Isabel Crawford, about whom I have written, who was sent by the American Baptists to work among the Kiowa in Oklahoma in 1893, and I am sure that there are many more missionaries who were transformed by contact with those whom they went to convert. Even if we hold reservations about going forth to “Christianize” the “heathens,” we are challenged and our views enlarged by hearing these stories of strong women. Thank you for sharing Lottie Moon’s story and your own powerful art work.

LikeLike

A very thought-provoking post! It made me think of my mother, who was raised as a Southern Baptist in the deep South in a very traditional family in the 1930s and 40s. She left the South and the Southern Baptist faith at a young age – at a time when that was rare for young women from her background to do – and made sure that she taught her daughters about the importance of equality and the Civil Rights movement and making our own spiritual way in the world. Yet, she named me after her favorite Southern Baptist Sunday School teacher. Despite all that she so vehemently rejected about the community in which she grew up, she found something valuable in that other Carolyn’s heart that she wanted to honor. I think you have done the same thing with Lottie and it is a good lesson that we can still honor and learn from the soul goodness of those who may hold and reflect times, attitudes, and beliefs that we reject.

LikeLike