I wake up each morning in a simple bedroom lit by the rising sun: a wardrobe, a bookshelf, a small wooden table, and a chair, arranged on painted plank floors. Just outside the window behind my head are the tallest trees I have ever seen, their grey-brown trunks growing straight up into a sky I cannot quite make out from my warm bed, with its white cotton sheets, white coverlet, and cozy down comforter. The room’s soft yellow walls reflect and amplify the winter light. Part of me wants to luxuriate, to lie here for hours, feeling the sun on my face as I gaze up at the trees and allow my consciousness slowly to return from dreams.

I wake up each morning in a simple bedroom lit by the rising sun: a wardrobe, a bookshelf, a small wooden table, and a chair, arranged on painted plank floors. Just outside the window behind my head are the tallest trees I have ever seen, their grey-brown trunks growing straight up into a sky I cannot quite make out from my warm bed, with its white cotton sheets, white coverlet, and cozy down comforter. The room’s soft yellow walls reflect and amplify the winter light. Part of me wants to luxuriate, to lie here for hours, feeling the sun on my face as I gaze up at the trees and allow my consciousness slowly to return from dreams.

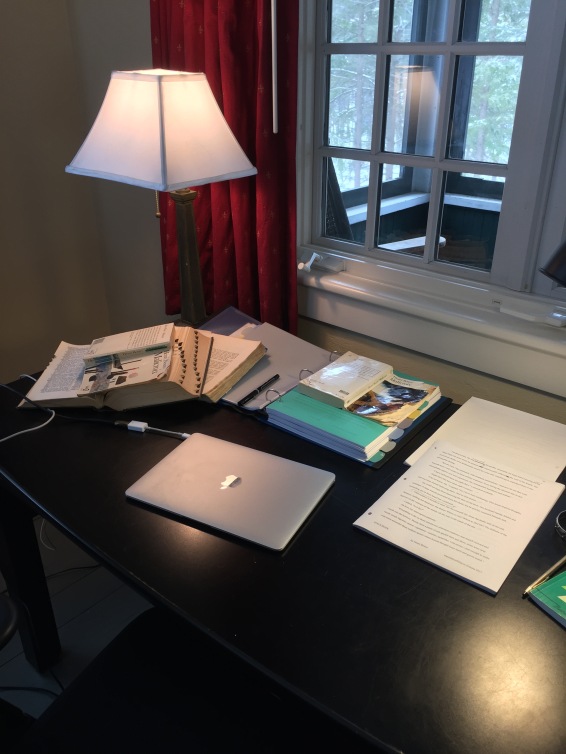

Yet I am here not simply to luxuriate but to work . . . in the next room is a desk, two desks actually, piled with books, folders, dictionaries, my HP Laser Jet printer, and my tiny laptop. From this room too, I can look out on woods and fields on three sides. Best of all, from the desk where I work, I can watch the sun set in the late afternoon.

Sunrise and sunset. And in between, a day entirely to myself, a day when I can work and dream at leisure, but during which I also feel impelled to stay on task, to complete the project that brought me here.

It has been my great good fortune to spend the entire month of February at The MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, NH. Founded in 1907 by Marian MacDowell and her composer husband Edward MacDowell, and supported today entirely by donations, the Colony is the oldest artists’ residency in the U.S., a place where some 300 artists —musicians, painters, dancers, writers, architects, filmmakers and more—each year enjoy what MacDowell is devoted to: the “freedom to create.” The Colony provides a congenial workspace, all meals, clean linens, and, best of all, the intangible gifts of validation and deep nurturing.

Among the many distinguished artists who have sojourned here are Suzan-Lori Parks, Alice Walker, Willa Cather, Leonard Bernstein, and Aaron Copeland, along with nearly eight thousand others. Of course, each day I ask myself if I really belong, but as the month has gone on, that question has come to seem less and less relevant. I am here, through some combination of effort and luck, and I am profoundly, profoundly grateful.

The moment I entered my little studio in the woods, a two-room cabin built before 1910, not far from the original farmhouse the MacDowells purchased in 1896, I felt entirely at home. With generous, multi-paned windows on all four sides, the isolated studio was exactly what I had hoped for when I applied for a residency in order to complete my translation of Henri Bosco’s 1948 French novel Malicroix. It is the perfect setting for my immersion in the language of this lyrical novel about a man spending several winter months alone in a small house in the wilderness, coming to terms with himself and the world around him.

I began this project over forty years ago, led to it by passages in Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, a book whose descriptions of the house as “a large cradle” (7) that “shelters daydreaming” (6) transported me. Throughout The Poetics of Space, Bachelard cites Henri Bosco, celebrating him for the “cosmic poetry” (22) that permeates his work, and singling out Malicroix as a “vast prose poem” (44) he returns to again and again. I knew I had to read it, but finding it only in French, my first language, I then knew I had to translate it—if only to better understand it myself.

The book, set in 19th century France, is the story of a young man, Martial de Mégremut, who leaves his comfortable home in Provence to live alone for three months on an island in the Rhône, in order to acquire the material and spiritual legacy bequeathed by his great uncle Malicroix, whom he has never met.

Mégremut’s name, which sounds like a combination of “maigre” (thin, weak) and “muet” (silent, mute), suggests his nature—timid and restrained. He envisions his great-uncle, who has lived alone in the wild Camargue for some fifty years, as “sauvage”—wild and independent. The name Malicroix combines the words “mal”—evil—and “croix”—cross—suggesting perhaps redemption for some initial sin. And the family motto, “Mal y croit qui tout n’y croit” – “Who believes not all believes but ill”—hints at the wild spaces to which this daring book–combining pagan and Christian symbolism–takes us, even while cradling us in its secure home.

To say that I identify with Mégremut would be an understatement. In leaving his village to encounter what he imagines to be his destiny in the Camargue, Mégremut must silence all the familiar voices, both internal and external, that urge him to stay safely ensconced within his family. He must break with the world he knows to face self-doubt and fear; he must trust the call of the hidden voice that dimly assures him he is on the right path.

In an essay written several years after the novel was published, Bosco called his central character a poet, and indeed, so he is—an artist bravely following his inner calling—like the people I am meeting here at MacDowell every day, people whose courage and commitment astound me.

Forty years ago, discouraged by the voices of publishers who told me the book was unmarketable, I abandoned my own inner quest to establish myself as a writer/translator. Worried about making a living and eager to reassure my family–whom I had broken from when I was seventeen–that I was now a responsible adult, I chose the relatively safer path of becoming an English professor, and I worked for more than thirty years helping others to find their voices. I do not regret taking that path. It has led me here.

And now I find that my dream, astonishingly, has become reality. All it took was finally listening to that inner voice. I look out at the woods today and breathe. I am home. Free to dream. Free to create. Free to be.

Joyce Zonana is the author of a memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey (Feminist Press 2008). She served for a time as co-Director of the Ariadne Institute for the Study of Myth and Ritual. She is the recipient of a 2017 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Award for her translation of Ce pays qui te ressemble by Tobie Nathan, forthcoming from Seagull Books. Her translation of Henri Bosco’s Malicroix is forthcoming from New York Review Books.

Discover more from Feminism and Religion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you Joyce for sharing your lovely post on your journey and dreams…. never give up that’s what I say AND never too old to have dreams and create them into a reality. Blissing.

LikeLike

Thanks so very much!

LikeLike

Love the house photo and all its simplicity, and what a wonderful place to live — the desktop too so inviting, thanks for sharing this, Joyce, Wow!

Also the “poetics of space” you mention reminded me of something quite amazing. According to the New York Post people are knitting sweaters to wrap around the street trees in the city to keep the trees warm. I linked my name here to a photo of one of those trees so beautiful, so crazy wonderful.

LikeLike

Wow! What happy trees! Thanks for sharing that photo, and for reading and responding to my piece!

LikeLike

Wonderful story Joyce! Love you! Keep hold of the Dream.

LikeLike

Thank you!!

LikeLike

Oh what a beautiful and inspiring story – I too abandoned my own path for the “safer” way – marriage children abandonment followed – and then finally I began my own difficult journey and slowly found a home within my self, and one embedded in the Earth. I am presently living in northern New Mexico in a trailer that overlooks the river in the east…and each morning I walk a little path to the river’s edge to watch the sun rise…at nightfall my animals and I all watch the sun set from our western window…as Venus rises. Each day begins and ends in a state of silent wonder…and I write…not any longer for others, but for myself. This is Grace manifest. Oh, I do wish you well.

LikeLike

How beautiful your life sounds, Sara . . . gorgeous. Grace indeed.

LikeLike

Full of beauty definitely – but also oh so hard

LikeLike

What a blessing! What sacred space. What sacred work.

LikeLike

Always.

LikeLike

A sacred space for the sacred work of creating! Thank you for sharing it with us, Joyce.

LikeLike

Thank you Barbara! It’s something we all should have and create for one another.

LikeLike

That looks and sounds like an incredible space for writing and creating! I feel empowered and inspired by your experience of being able to fulfill a life-long passion and the embrace you’ve made of the journey that led you there.

LikeLike

Thank you Suzanne. May you also find your way to such spaces and such creation! I feel so fortunate to have lived long enough to get here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing your inspiring story and pictures of your lovely home in all its simplicity. You really inspired me, thinking of how I like to spend my age.

LikeLike

Yes . . . we get to choose now!

LikeLike

Lovely, Joyce, that you now have the time to pursue this dream in such a perfect environment!

LikeLike

Thank you Joannie! Yes, it’s such a great gift!

LikeLike

Such a beautiful post – honest and heartfelt. It has given me the courage to pursue my writing dreams at almost 60.

LikeLike

How wonderful. I guess I wrote the piece for you! Follow the dream, absolutely!

LikeLiked by 1 person