“Nothing is so simple, or so out of the ordinary for most of us, then attending to the present.”

— Ernest Kurtz & Katherine Ketcham, The Spirituality of Imperfection

I often speak of being in the temple of the ordinary, of seeing the enchantment in the ordinary. In the book The Spirituality of Imperfection, the authors write that “beyond the ordinary, beyond material beyond possession, beyond the confines of the self, spirituality transcends the ordinary, and yet, paradoxically, it can be found only in the ordinary. Spirituality is beyond us, and yet it is in everything we do. It is extraordinary. And yet, it is extraordinarily simple.”

This spring, I presented at an event and the concept of “being versus doing” arose. I reminded participants that “being” is not a competitive sport. We cannot not be, we are being all the time. I think sometimes the pressure we put on ourselves to be better, to “do” being better, can be really hobbling. Likewise, the sensation that spirituality is somewhere “out there” or that it has to be bigger than or better than or transcendent instead of present in the ordinary. On a goddess based path, with a feminist orientation, I find that the Goddess herself pervades all of existence, pervades your whole entire life, even the rough and weary places, even the ragged and strange places. Returning to Kurtz and Ketcham, they write: “Now…beyond the ordinary is not meant to suggest something complicated, different, different or self-consciously special. Nothing is so simple, or so out of the ordinary for most of us, then attending to the present. The focus on this day, suggested by all spiritual approaches, attending to the present, to the sacredness present in the ordinary, if we can get beyond the ordinary is, of course, a theme that pervades Eastern expressions of spirituality and other expressions too.”

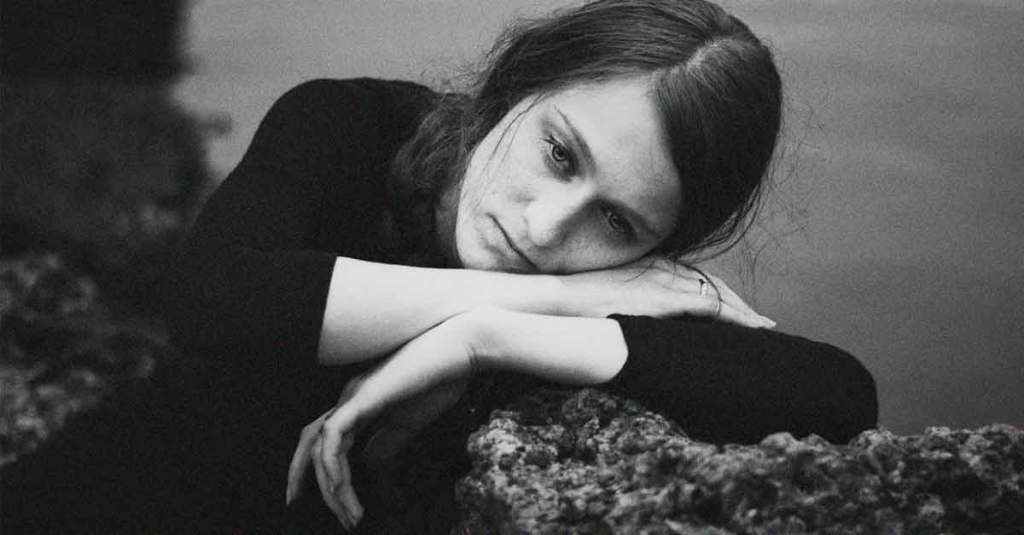

I know that I often find myself seeking or longing for the special moments, the magic, the flashes of transcendence, and sometimes this can cause me to miss the ordinary, to miss the present, to miss where I am because I’m longing for something else. Adages to the effect of “do what you are doing” and “be where you are” may begin to sound cliché almost and the reason they do is because it’s so simple and so out of the ordinary to simply come back to attending to the present. The present moment is, in my eyes, truly where we find the goddess, in the pulse of presence in the every day. In the book She of the Sea, author Lucy Pearce addresses the question of the transcendent ordinary as well: “I want to write of the oceanic mystery, the soul of goddess magic, the sacred that which lies beyond words, because the repeated deliberate seeking of connection to this is at the heart of what I do and who I am. It is my creative and spiritual practice. I want to speak of this so that you can close your eyes turn inwards and smile knowing, just knowing until our conversation can continue without words…I want to share what I have known and for not to sound strange, yet strangeness is its nature. The soul is not of this world. It’s not rational, the sacred is not logical, but nor is this chaotic, magnificent, contradictory, and complex world of ours. And yet, we insist on pretending that it is and being disappointed, afraid, or bemused when it shows us its reality, again and again.”

The sacred is not logical, and neither is the world itself, but we pretend that it is, and then we get disappointed when we see reality. I originally learned the phrase “don’t argue with reality” from self-help author Wayne Dyer. There can be a whole range of potential experiences that are beyond objective reality or the reality that people sometimes insist is all there is. Jeanette Winterson, in her book Lighthousekeeping writes: “I do not accept that life has an ordinary shape, or that there is anything ordinary about life at all. We make it ordinary, but it is not.”

Maybe we are trying to make things ordinary that are not. My kids are growing up and getting ready to graduate from high school. One of my sons is very into science and loves biology and genetics and he is fond of boiling things down to an “everybody’s just a mass of cells having a collective hallucination” type of rhetoric that leaves little room for the esoteric and little room for inherent meaning. However, for me, I come back to the reality of being human as its own kind of miracle, its own profound magic. The reality of having this body with all these cells, which are doing all these things day in and day out that I don’t consciously know how to do, and yet my body does them every single day. That’s magic, even if we can explain the objective “why” of it. I don’t consciously know how to beat my own heart, but wait a second, yes, I do, because here it is beating every day from birth till death. Some people may be quite attached to maintaining the assertion that life is random and pointless, but this is not the story I see. I see wonder. I see magic. I see a miracle in motion. I am awestruck at the impossible reality of being a bundle of cells typing this essay right now. Yes, I am “only” a bundle of cells and that is absolutely pure magic to me. In fact, your very presence right here, right now is proof of the sacred on this earth in my eyes. May we all love the ordinary and let it whisper of the magic right beneath the skin.

Breathe deep

and allow your gaze

to settle on something you love.

Draw up strength from the earth.

Draw down light from the sky.

Allow yourself to be refilled and restored.

There is good to be done on this day.

Let your own two hands

against your heart be the reminder

you need

that the pulse of the sacred

still beats

and the chord of the holy yet chimes.

Molly Remer, MSW, D.Min, is a priestess facilitating women’s circles, seasonal rituals, and family ceremonies in central Missouri. Molly and her husband Mark co-create Story Goddesses at Brigid’s Grove. Molly is the author of nine books, including Walking with Persephone, Whole and Holy, Womanrunes, and the Goddess Devotional. She is the creator of the devotional experience #30DaysofGoddess and she loves savoring small magic and everyday enchantment.

Tobie Nathan’s panoramic novel about Jews and Muslims (and Christians) in early twentieth-century Egypt,

Tobie Nathan’s panoramic novel about Jews and Muslims (and Christians) in early twentieth-century Egypt,